Belated happy Pioneer Day, everyone!

“Happy what?” you might be asking. That is, if you’re not from Utah, where July 24—the anniversary of the arrival of Brigham Young and the first Mormon* pioneers into the Salt Lake Valley in 1847—is a state holiday, a sort of second Fourth of July.

I’m in Provo for the week, in the role of conference spouse. Unfortunately, they moved the celebration away from downtown this year because Pioneer Park is being renovated, so I didn’t get to attend,

but last night I watched from my hotel room as fireworks went off all across town, the mountains that ring the city serving as a backdrop.

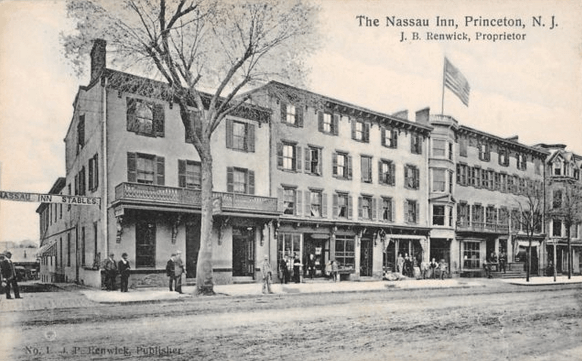

Provo, the home of Brigham Young University, is an attractive little city. Eighty-eight percent of greater Provo is Mormon, the highest proportion in the state (and, ergo, the country). This figure is a bit misleading because it counts BYU students, but still—it’s pretty Mormon. Especially on Sundays, when stores and restaurants are closed and the streets are empty except for people going to and from church. I felt self-conscious walking around in pants.**

Provo is surprisingly hip, though, with funky stores

and a cool coffee*** shop

and my favorite used book store ever, Pioneer Book.

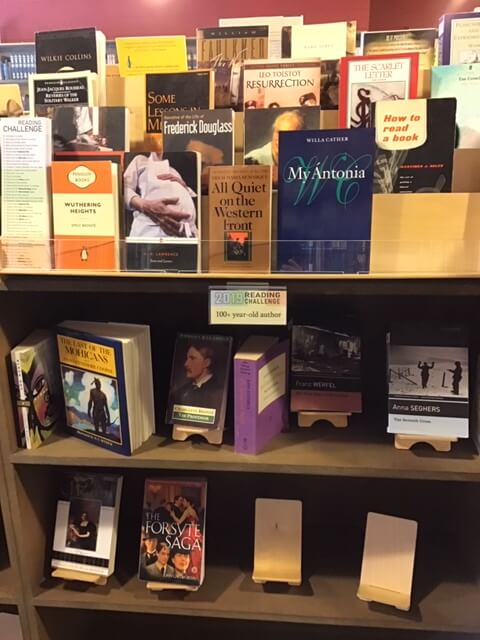

I’m not a fan of used bookstores in general—I hate the musty smell, the lack of order, and the “here’s a bunch of stuff people didn’t want” atmosphere. Pioneer, though, is like a new bookstore where the books just happen to be (lightly) used. The sales counter is made of books

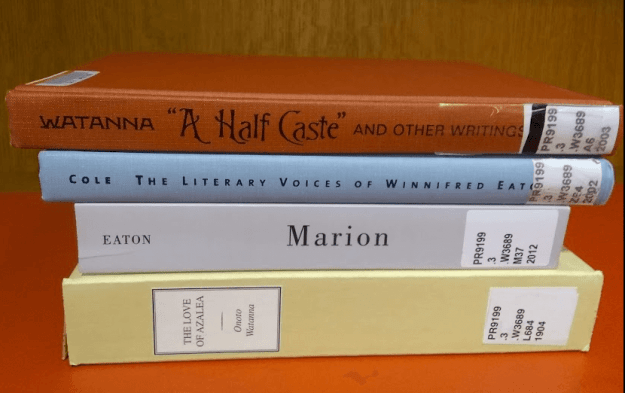

and there are displays highlighting categories from their 2019 reading challenge, like books by women,

books by writers born more than 100 years ago,

and books that you disagree with.

There’s also an entire long wall of books on Mormon history.

Yes, history. I’m getting to that.

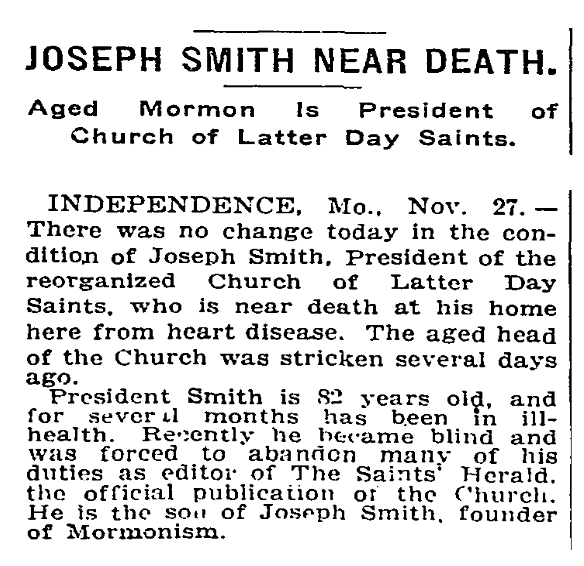

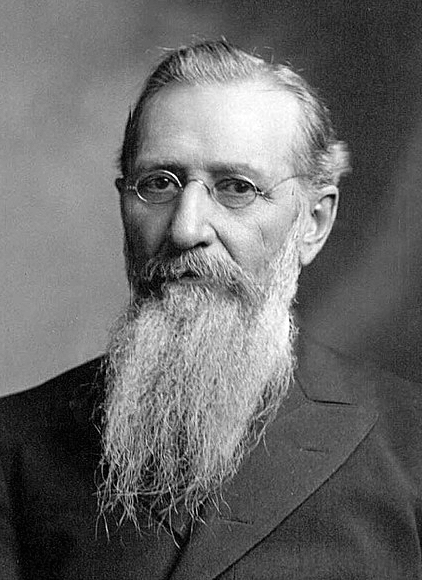

A hundred years ago, the Mormon church was in transition. Longtime president Joseph F. Smith died in November 1918 after a long period of ill health. This 1914 New York Times article about his imminent death is totally accurate except that he lived for four more years, was 76 at the time, not 82, and was church founder Joseph Smith’s nephew, not his son.

When Smith actually did die, the Times (having gotten the facts about his age and paternity straight by now) noted that he was the last of the Mormon leaders to have made the trek to Utah. He was five years old when Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum, who was Joseph F.’s**** father, were killed by a mob that stormed the Illinois prison where they were being held. When he was eight, he set out with his mother for Utah, driving an ox team. Smith married his 16-year-old cousin when he was 21, married five other wives, and had 45 children.

It was under Smith’s leadership, though, that the church cracked down on polygamy, or plural marriage as it was known. His predecessor, Wilford Woodruff, had prohibited new plural marriages in the Manifesto of 1890, but many church members (and, apparently, leaders) took a wink-wink-nudge-nudge attitude, seeing the Manifesto as a political move. The Supreme Court had just upheld a law prohibiting polygamy, and the issue was standing in the way of statehood for Utah. Smith, who took over as church president in 1901, issued the “this time we really mean it” Second Manifesto in 1904.

The Second Manifesto was issued during a bizarre political episode following the 1903 election of Reed Smoot, a Utah Republican, to the U.S. Senate.***** A number of Protestant groups petitioned the Senate to refuse to seat Smoot, who was a Mormon apostle. They had precedent on their side, in a way: Utah Democrat B.H. Roberts, who was elected to the House of Representatives in 1898, was barred from taking his seat because he was a polygamist. Reed, though, had only one wife. That didn’t deter his critics, who argued that as a senior church member he was part of a conspiracy to promulgate polygamy. Smith was allowed to take his seat, but the matter was referred to the Senate’s Committee on Privileges and Elections, which deliberated for four years. Some three million people signed petitions opposing Smoot, and the committee hearings attracted standing-room-only crowds. Smith spent six days testifying in 1904, wearing a pin depicting his slain father. He discussed Mormon church doctrine in detail, but it was the revelation that he had five wives that riveted the press and public.

Smoot’s fate was finally settled in 1907, when the Senate voted 42-28 to allow him to remain. (It would have taken a two-thirds majority to expel him.) He went on to co-sponsor the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, a piece of protectionist legislation that is widely considered to have contributed to the Great Depression.

In October 1917, Smith made one last effort to eradicate plural marriage, leaving his sickbed to denounce its continued secret practice at a church conference.

Smith, though, stayed married to his five wives,****** arguing that, having married them while plural marriages were still allowed, he couldn’t abandon them.

So what was it like to be a woman living in a society where plural marriage was widely practiced? In 1915, Harper’s Weekly published an article, titled “Harp Strings and Shoe Laces,” telling an anonymous Mormon woman’s story. The author writes that she was serving as the head of the music department at “one of the largest institutions on the coast,” with marriage far from her mind, when, at the age of 21, she was swept off her feet by a Mormon colleague. The 28-year-old married father of two gave her a ride in his carriage, presented her with a box of bonbons, and declared, “I’ve been in love with you ever since I first saw you.” The woman writes that

to a girl raised in any other way, such a confession from a married man would have been shocking and repulsive. I had been raised to revere every tenet of my religion. The principle of polygamy was a sacred thing. It was a revelation from God.

To lightly turn aside a confession of love from a single man was my woman’s prerogative when I chose to use it. To refuse an opportunity to enter that “sacred covenant” carried with it a superstitious dread of ill consequences to follow—I dared not invoke.

Her suitor tells her that he knows an apostle who will marry them despite the church ruling against plural marriage. She tells him to write to her father, who agonizes about whether to give his blessing, hesitant to subject his own daughter to the arrangement despite being a polygamist himself. Meanwhile, she starts to have second thoughts.

While I was still under the glamour of it all—in love as a girl can be only once, whether it be real or false—suddenly the thought came: two was polygamy—a test of the principle—a preparation for eternity—would he ever want a third? My heart contracted at the thought.

It occurs to her that this may be how her suitor’s wife—who hadn’t entered into her thoughts until now—is feeling. When she expresses her hesitation, he offers to divorce his wife.

“Divorce her!” I exclaimed, amazed. “But that would not be polygamy!”

She turns him down, her heart broken, and becomes aware of the shattered lives around her. She tells of her father, a successful businessman and community leader whose career was destroyed when he took a second wife. Of a young woman who went to Mexico to become a seventh wife and returned home with her baby, heart and health broken, to die. A woman whose children were taken away from her so her plural marriage would not be discovered.

Day by day, from an upper window, she watches her two sturdy little sons trudging to school—her heart aching to clasp them in her arms—not daring to let even them know of her whereabouts.

This woman’s story is intriguing and well told, but it left me wondering whether it was actually true, as Harper’s Weekly insisted. The writer speaks of polygamy rather than plural marriage, the term used within the church. The writing is surprisingly polished for a non-professional writer. Would a music instructor barely out of her teens write this?

I am not criticizing my church. I am not palliating the principle. If ever there were a people honest and sincere in their belief, it is my people; but they have ruined their lives for a pathetic fallacy.

I have my doubts.

I’ll ponder this, and think about Utah’s history, as I spend my last day in Provo.

Or maybe I’ll take a break from history and get some ice cream. Did I mention the ice cream?

*Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints were recently instructed by their president not to use the word “Mormon” or the abbreviation “LDS” anymore. This has required a great deal of reshuffling. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir, for example, is now the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square. “Mormon” is still used in historical contexts, though.

**This list of things to do in Utah on a Sunday includes, I kid you not, “take a nap.”

***Yes, Provo does have coffee shops, although they’re not as ubiquitous as in other cities. I was surprised to see a large number of Coke and Pepsi dispensers around town, including in the BYU student common (highly recommended, and practically the only place to eat on Sunday, after church ends at 1-ish). It turns out that that the church made an official statement in 2012 saying that caffeinated soda is allowed.

****That was what church members called him—Joseph F.

*****In case you’re thinking, like I did, this is a mistake and it’s supposed to be 1902, members of the Senate were elected by state legislatures at the time, and Utah’s election took place in January 1903.

******His first wife, unhappy with the plural marriage arrangement, had divorced him.

New on the Book List: The Circular Staircase, by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1908)