Happy holidays, everyone! It’s been a while.

Last year, I grumbled that my go-to children’s book resource, pioneering children’s librarian and Bookman columnist Annie Carroll Moore, was too busy waxing whimsical to make book recommendations. The year before, I moaned about the poor selection of books on offer.

Be careful what you wish for. This year I was hit with a veritable firehose of books. And I wasn’t the only one who felt that way: “Books for children continue to pour from the presses much faster than descriptions of them can be hammered out on the typewriter,” says the anonymous, but very relatable, writer of the Children’s Bookshelf column in the December 10, 1922, New York Times.

Over at The Bookman, Moore is back on form, wasting only the first page of her October 1922 column on flights of fancy (something about an imaginary train ride, don’t ask) before going on to six pages of solid recommendations.

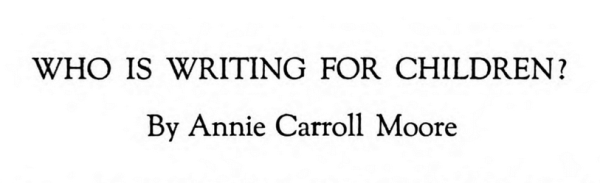

Fellow children’s book columnist Marian Cutter weighs in in the December Bookman, but mostly about classics.* She and others, like Library Journal and The World’s Work,** are abuzz about a list of the best books for children that a group of librarians and educators had come up with. The idea is that, if you have a one-room schoolhouse and a limited budget, these are the books you should buy. Other than the boy-specific titles and some colonialism, the list holds up pretty well today. Little Women is the runaway winner, followed by the two Alice books, Robinson Crusoe, Tom Sawyer, and Treasure Island, followed by:

Publishers Weekly’s November 4 holiday issue has its usual extensive listing of children’s and every other kind of books, along with ads that are just as much fun. My only regret was that the snarky blurb writer of last year has been replaced with a more temperate colleagues (or else it’s the same guy and he’s recovered from last year’s burnout).

The October 1, 1922, issue of The Library Journal featured a charming article, originally published in the Manchester Guardian Weekly, called “The Books Children Like.” The writer, Evelyn Sharp, is a British suffragist and children’s book writer.*** “One has to be what is called a children’s author, perhaps, to know what it feels like, after writing a book for children, to discover that one has written a very nice story for fathers or aunts,” she sighs. The biggest mistake children’s writers can make, she says, is writing down to children, and the best children’s books are “the ones that make him feel on a level with the author, whether it is actually written for them or their elders.”

So here I am faced with an embarrassment of riches, which is great, except that the holiday season is ticking away, I have a huge (virtual) pile of books to get through, and seasonal activities keep getting in the way.**** So I’ll have to fly through the selection at a torrid pace. Here goes!

Fairy Tales, Nursery Rhymes, and Folk Tales

I was underwhelmed by Fairy Tales from Far and Near, written and illustrated by Katharine Pyle, with its muted illustrations and plethora of thous, thees, and thys.

Frances Jenkins Olcott’s retelling of Grimm’s Fairy Tales is a better choice. It’s told in refreshingly non-faux-archaic language, and Rie Cramer’s illustrations are brighter and more numerous than Pyle’s.

Back in 2020, I was charmed by Rose Fyleman’s Fairies and Chimneys, which mixed magic and city life a la Mary Poppins, but The Fairy Flute just isn’t doing it for me. It’s just a bunch of poems about what to do if you come across a fairy (bottom line: don’t run away), with no illustrations. Plus, the first poem, “Consolation,” tells you that the fairies will love you even if you are “very ugly and freckely and small.”

Moore calls Parker Fillmore’s Mighty Mikko, a collection of Finnish tales, “a capital piece of work.” It’s an attractive volume, illustrated by Jay Van Everen, whose small wood-block drawings, like the ones on the lining pages above, I prefer to the full-page illustrations.

My most fascinating discovery of the year was Taytay’s Tales, a collection of American Indian stories collected by Elizabeth Willis De Huff. I skipped over it at first, since Moore said that “some of the tale are like Uncle Remus stories,” which wasn’t exactly a draw. It showed up on all the lists, though, so I decided to take a look. De Huff says that the book was illustrated by two Hopi teenagers, including 17-year-old Fred Kabotie. Since books by fake Native Americans are common even now, I was suspicious, but, it turns out that Kabotie not only was for real, but he went on to be a renowned artist whose honors included a Guggenheim fellowship and France’s Palme Academique. Two of his paintings are in the collection of the National Gallery of Art.

The stories in Rosetta Baskerville’s The King of the Snakes, advertised as Ugandan folk tales, also seem to be authentic—at least, the creation myth is—and E.G. Morris’s illustrations are respectfully done. On the other hand, “Ndaba kuki basebo, basebo ndaba kuki,” which is supposed to mean “The Song of the Forest Wanderer,” comes out in Google Translate as meaning “I see cookies, guys—guys, I see cookies!” in the Ganda language.

For Young Children

Luis Coloma, a Spanish priest and Royal Academy member, was commissioned to write Perez, the Mouse (originally Ratoncito Pérez) in 1894 for eight-year-old King Alfonzo XIII, who had lost a tooth. Perez lives in a box of cookies with his family and runs through the city’s pipes to the rooms of children who have lost their teeth. To this day, children in Spanish-speaking countries to this day leave their teeth under the pillows for the mouse. This 1914 version, reprinted in 1922, was adapted by Lady Moreton with illustrations by George Howard Vyse. “A great favorite with children,” Moore calls it, and I can see the appeal.

Sarah Addington’s The Boy Who Lived in Pudding Lane, illustrated by Gertrude A. Kay, is Santa’s origin story. “The younger children will be amused to read how the very fat little boy who always wore a red suit came to make toys for all children the wide world over,” Cutter tells us.

For Middle-Grade Readers

The Adventures of Maya the Bee by Waldemar Bonsels, illustrated by Homer Boss, was published in German in 1912 and (after a postwar cooling down period, presumably) first appeared in English in 1922. It’s the story of Maya, a bee who gets caught up in bee-hornet warfare. “One of the most delightful insect stories every written,” Cutter raves, which strikes me as a low bar. In any case, I’m not enthusiastic about the German militarism angle, plus the pictures freak me out, so I’m passing.*****

Kay Nielson’s illustrations for Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Engebretsen Moe’s retelling of the Norwegian fairy tale East of the Sun, West of the Moon are beautiful—she’s like the Erté of children’s book illustration—but the story itself is way longer than a fairy tale has any business being. Too bad, because I’ve always loved that title.

Ralph Bergengren’s David the Dreamer came out too late for Moore’s roundup, but Cutter gave it a rave review, and Tom Freud’s illustrations are sprinkled through the article. I couldn’t find a copy online, and when that’s the case I usually skip the book. Plus, who wants to read about someone else’s dreams? But then I found this blog post from The Marginalian (formerly Brain Pickings) about how Tom Freud started life as Sigmund Freud’s niece Martha but, at age fifteen, took on the name Tom and began wearing men’s clothes. Plus, just look at that illustration. (And lots more at The Marginalian.) Freud, sadly, committed suicide in 1930 at the age of 37.

For Older Children

Moore is quite taken with the whimsy of Gypsy and Ginger, about a carefree couple who get married right after they meet, like Dharma and Greg without the sexual innuendo. Me, not so much.

“The Southern slaves were childlike people,” Maud Lindsay says in Little Missy, a tale of life on the old plantation. And that’s just on page 1. I didn’t make it to page 2.

For Older Children

“Books written for girls present the usual problem,” Moore says, but doesn’t explain what the problem is. This is my fourth year on the beat, so I think I know what she means: they’re boring. I had high hopes for Red-Robin by Jane Abbott, though, since it had gotten rave reviews. I was sorely disappointed. If you think I’m just being grumpy, here’s the opening:

“Maybe she’s just setting the scene,” I said, trying to be fair, so I skipped to the next chapter, which started with more description. As I browsed, I encountered dialect, our heroine calling her father “Father dear,” and a young man who seemed promising at first (walking out of the store he works at, whistling, paying not the slightest attention to the sky) but then ruined everything by saying, “Giminy Gee!”

Moore says that the 1922 edition of Charles and Mary Lamb’s 1807 Tales from Shakespeare, with illustrations by Kay Nielson, is “perhaps the most distinguished in form of the books of the year,” and I can see her point. I would definitely get this for 13-year-old me.******

The standout poetry anthology for children in a season full of them, the critics say, is Rainbow Gold by Sara Teasdale. “Miss Teasdale works on the assumption that children prefer the poetry of such figures as Wordsworth, Tennyson, and Swinburne to what may be termed professional children’s poetry, and she is correct,” the New York Times reviewer says. I agree—I would buy this for thirteen-year-old me too. The frontispiece is, disappointingly, the only color illustration in the book, but, as a Dugald Walker fan from way back,******* I’m happy with his black-and-white Art Nouveau illustrations.

Oh, wait! I forgot something. As much as I balk at the gender-specific reading lists of 1922, I have to admit that there’s a good swath of the adolescent male population that isn’t going to happy with any of these choices. Well, I have just the thing for them! Won for the Fleet: A Story of Annapolis by Fitzhugh Green (Lt.-Commander – U.S.N.) is a rollicking tale of…well, I just skimmed through the beginning and there was Naval Academy hazing (with trash talk like “Oh, you slacker! Oh, you kindergarten kid!”) and someone’s father’s financial ruin and I think a battle in Cuba. It was a bit confusing, but definitely rollicking.

For Young Adults

Young adults want to read about actual adults, not about fake for-children’s-consumption adults like Gypsy and Ginger. And what could be more entertaining than reading about the out-of-control party couple Anthony and Gloria Patch in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s second novel, The Beautiful and Damned? Well, honestly, I found it a bit boring when I read it during my freshman year in college, and critics generally agree, but subpar Fitzgerald is better than peak almost anybody else.

Or, if that young person in your life needs help finding a partner (and hasn’t been scared away from the whole idea by The Beautiful and Damned), there’s always Dancing Made Easy, by Charles Coll and Gabrielle Rosiere. It is the tragedy of my life that I have never hung out with a crowd that does dances like this:

Classic or Not?

The following 1922 books make a claim for the title of “classic,” or at least fall into the category “really old but I’ve heard of it.” Let’s see how well they hold up.

I remember being so eager to get back to The Voyages of Dr. Dolittle, Hugh Lofting’s Newbery Medal-winning sequel to The Story of Dr. Dolittle, that I woke up early to read it in bed. What can I say? My racial politics weren’t very evolved when I was nine. Luckily, I don’t have to dig around in the book for all the racism because Sara Beth West did it already in this excellent blog post, part of a series on Newbery winners. She says that, while some egregious passages have been removed, “the edition I read was still thoroughly offensive.” Example: a monkey successfully disguises himself as a black woman to get passage on a ship. Not a classic!

Moore is a big fan of Carl Sandburg’s Rootabaga Stories, which plays a big part in the aforementioned incomprehensible whimsical journey. I looked at the first page, which featured characters named Gimme the Ax, Please Gimme, and Ax Me No Questions, and could get no further. Which may be unfair, but do you know of anyone who has actually read this book? I don’t. Not a classic!

The Velveteen Rabbit, by Margery Williams, is one of those books that was always lurking around when I was a child but that I never got around to. It was old and about animals, so it had two strikes against it. Adult me was charmed by it, though. It’s the story of a toy rabbit that is initially ignored in favor of flashier, but breakable, mechanical toys but eventually finds its way to a boy’s heart and, thereby, life as a real live rabbit. It has humor that I actually found funny, like the self-importance of the other toys: “Even Timothy, the jointed wooden lion, who was made by disabled soldiers, and should have had broader views, put on airs and pretended that he was connected with Government.” Finally—a classic!

So that’s it! This is definitely the best holiday children’s book selection I’ve come across. There’s something for everyone. And it’s only 9:30 p.m. at Christmas Eve Cape Town Time, which is 2:30 p.m. or earlier if you’re in the United States, which, if you’re celebrating Christmas, gives you HOURS to get your shopping done.

Best wishes for the holiday season, everyone!

*I learned from this fascinating post on the blog “Bibliophemera” that Cutter was the founder of the first children’s bookstore in New York.

**I had the idea that The World’s Work was a socialist magazine, but it turns out to be a pro-business magazine with stories like “How a Business Man Would Run The Government.”

***Evelyn Sharp gossip: She and her best friend’s husband were in love for many years. They married after the friend died, when Sharp was 63 and her husband was 77.

****I returned to Cape Town from Washington, D.C., this week, and the obligations are along the lines of picking young people up at this beach, so I’m not expecting a lot of sympathy.

*****The film industry was more enthusiastic, and Maya’s story was recently made into a series of animated films.

******14-year-old me would have turned my nose up at Lamb and plowed uncomprehendingly through the original text.

*******Although I see I misidentified him both of the times I’ve mentioned him, calling him Dugald Steward Walker one time and Dugald Stewart the other time (although I may have fixed these errors by the time you read this). His actual name was Dugald Stewart Walker.