Happy holidays, everyone! This year’s Holiday Shopping Guide is devoted to books, because who doesn’t love a book? Well, lots of people, but, when I looked for gift ideas in the December 1919 issue of Vanity Fair, this monogrammed humidor ($30.00)

and this kit bag ($118.50)

and this vicuna bath robe ($70.75),

to say nothing of this solid platinum opera watch with gold hands and numerals ($800.00, plus $96.00 for the chain),

all cost more than the average weekly wage of $25.61. I’m feeling more egalitarian than that this season, so books it is.

My original plan was to review books for all ages, but the children’s books ended up taking up a whole post. I have the books for grown-ups all picked out and will try to write about them as well, but I’ve learned not to commit myself to future posts because they hardly ever happen. (UPDATE 12/13/2020: This one didn’t either.)

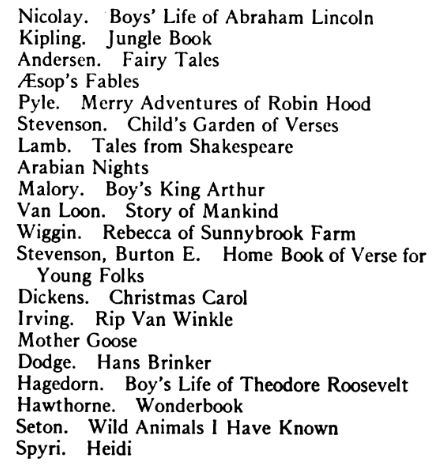

I had a lot of help with this gift guide. New York chief children’s librarian Annie Carroll Moore, whom I wrote about earlier this year, has a holiday book roundup in the November issue of The Bookman. Boston chief children’s librarian Alice Jordan* has recommendations in House Beautiful, and Elementary School Journal and Literary Digest chime in as well. Library Journal, taking its sweet time about it, published the results of a vote among children’s librarians on the best children’s books of 1919 in its December 1920 issue.

Books With Color Illustrations

Children’s picture books as we think of them today, with a color illustration on every page, didn’t exist in 1919. Even books for very young children consisted mostly of text, with occasional line illustrations and a few color plates. If my own experience of reading to children is any guide, small children of a hundred years ago would push the pages impatiently to get to the pictures, leaving the adult reader to come up with a highly abridged version of the story on the fly. So the pictures are the key.

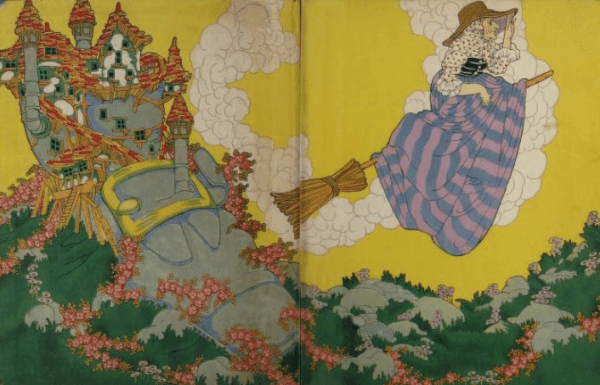

Moore was so entranced by The Firelight Fairy Book by Henry Beston, with illustrations by Maurice Day, that she went to Boston to meet Beston. He turned out to be a World War I veteran who started writing one of the tales, “The City Under the Sea,” IN A SUBMARINE IN ACTIVE PURSUIT OF GERMAN SUBMARINES, which is a great story, if not exemplary military tradecraft.

Maurice Day, The Firelight Fairy Book

Maurice Day, The Firelight Fairy Book

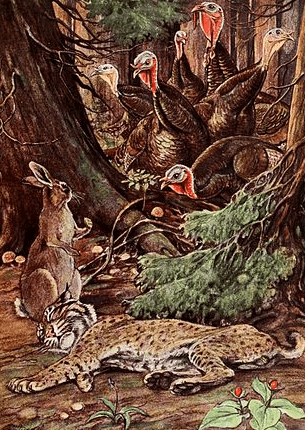

Moore wasn’t as big a fan of Day’s illustrations in a new edition of Horace E. Scudder’s Fables and Folk Stories—“his animals might be stronger”—but I was quite taken with this one:

Maurice Day, Fables and Folk Stories

Some other illustrated books Moore discusses with varying levels of enthusiasm:

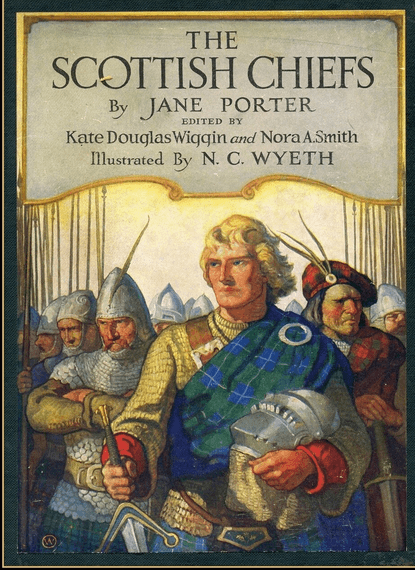

Czechoslovak Fairy Tales by Parker Fillmore, with illustrations by Jan Matulka,

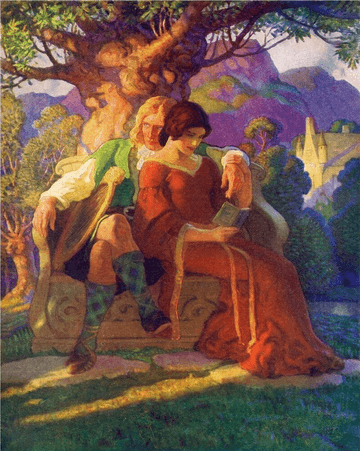

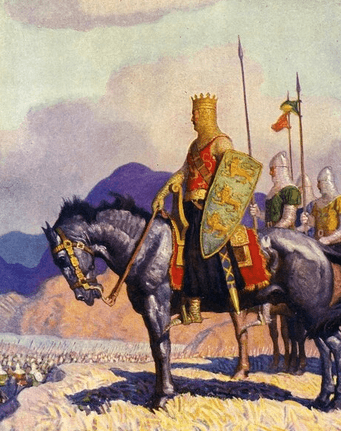

The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper, with new illustrations by N.C. Wyeth,

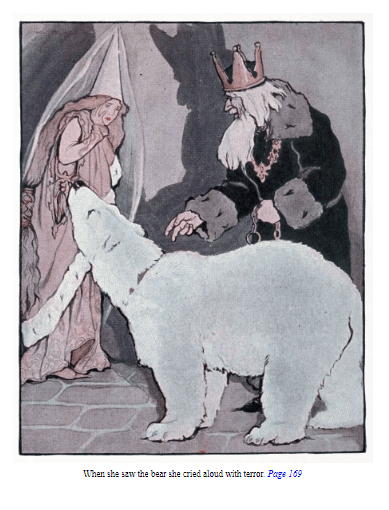

At the Back of the North Wind by George MacDonald, with new illustrations by Jessie Willcox Smith,**

a new edition of The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley, also illustrated by Jessie Willcox Smith,

Saint Joan of Arc by Mark Twain, with new illustrations by Harold Pyle,

and Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes, with illustrations by Boyd Smith.

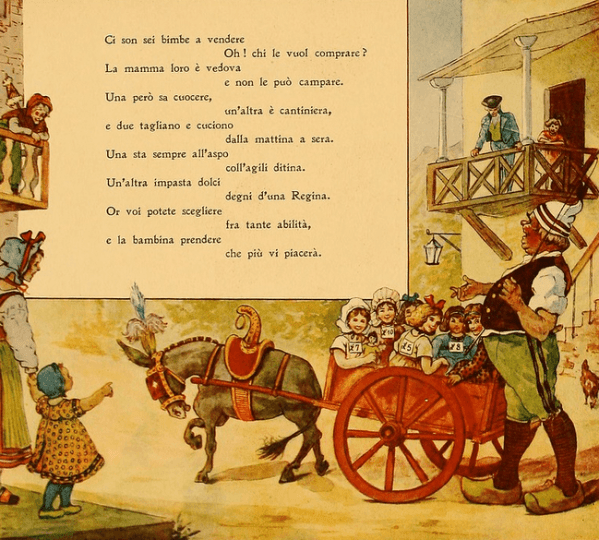

Caveat emptor on this last one. As I was perusing Smith’s illustrations, finding them quite charming, I came across this one,

which turns out to illustrate this poem,

which I don’t recall my mother ever reciting as she lulled me to sleep.

I imagined Thornton Burgess’s The Burgess Bird Book for Children as a reference for budding Audubons. It turned out to be full of twee tales, such as one in which Jenny Wren meets up with Peter Rabbit, who was Beatrix Potter’s intellectual property, right? The pictures by the Dutch-Puerto Rican artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes*** are wonderful, though.

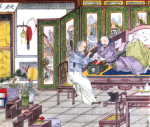

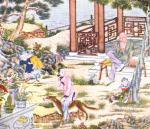

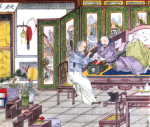

Alice Jordan had good things to say about A Chinese Wonder Book by Norman Hinsdale Pitman, illustrated by Li Chu-T’ ang. I was intrigued, especially because Jordan said that Li was Chinese. I loved the illustrations,

but I wondered whether Pitman was one of those people who make up stories and claim they’re foreign folk tales. He turned out, though, to be an American professor who spent many years teaching in China and won several awards from the Chinese government, so presumably he knew what he was talking about.

This is as multicultural as children’s books get in 1919, so I was inclined to declare it my #1 recommendation in this category. To make sure I wasn’t leading you astray, I read one of the tales, “Lu-San, Daughter of Heaven.”

What young person wouldn’t relate to the story of a girl whose parents don’t appreciate her (that’s putting it mildly—they’re always trying to sell Lu-San into slavery or kill her) but end up having to kiss her feet and watch as she ascends to heaven on a golden throne? I liked the girl-power theme (Lu-San’s brothers are treated like kings) and the realistic way her parents respond after Lu-San is transformed into a radiant princess and their dingy houseboat into a majestic ship:

At first they did not know how to live as Lu-san had directed. The father sometimes lost his temper and the mother spoke spiteful words; but as they grew in wisdom and courage they soon began to see that only love must rule.

So it’s official: A Chinese Wonder Book is my #1 recommendation.

For Middle-Grade Readers

There is a lot of blurring between these categories; many of the books mentioned above are appropriate for middle-grade readers as well. Here are some selections specifically for this age group.

Or not. Sometimes Moore just makes me scratch my head.

For example, what is Susan Hale’s Nonsense Book doing in a children’s book roundup? That the handwritten limericks are illegible is the best thing that can be said about them.**** Would you read this tale of death by jumping out a window

or this one of suicide by exposure

to your favorite nephew?

Moore pans John Martin’s Big Book for Little Folks, No. 3. I couldn’t find it, but I did find the 1917 volume. It starts out with this poem,

which reminds me of the fairy tales that simpering old ladies inflict on the kids in the Edward Eager books (now THERE are some great books for middle-grade readers).

Next up is the world’s least challenging riddle.

So I’m on board with Carroll even before she quotes from Martin’s story about Thoreau:

He was so kind! and he was a busy man too. He built his own house. He had a garden. He made lead pencils. He wrote books. Most likely we never did know a busy man who was more kind than he was to everybody—animals and all—children and all. No wonder he became a very famous man.

As we will see below, kindness to animals and fame do not always go hand in hand.

Moore describes What Happened to Inger Johanne, a translation of an 1890 book by the Norwegian writer Dikken Zwilgmeyer (UPDATE 12/22/2019: who turns out to be a woman, real name Barbara Hendrikke Wind Daae Zwilgmeyer),

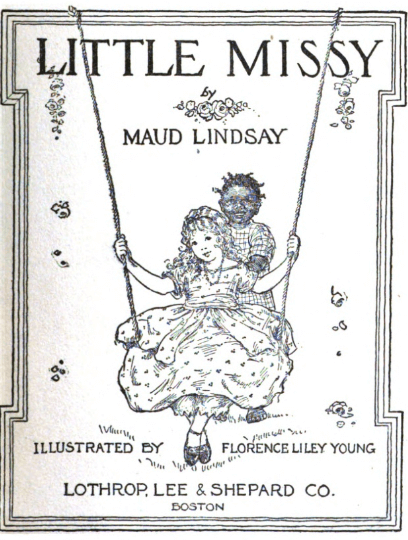

as “alive from beginning to end.” It’s a miracle that Inger herself is alive from beginning to end. In the illustrations by Florence Liley Young, she and her friends fall out of a boat,

get stuck in a barn window when the ladder breaks,

smash a window with a book,

and get lost in the woods.

The chapter on Christmas mumming is less harrowing. My favorite part is where the children speak P-speech, which turns out to be a Norwegian version of Pig Latin. It goes (in the English translation) like this: “Can-pan you-pou talk-palk it-pit?”

A “child of ten”—who I assume is our old friend Edouard from last year’s holiday roundup—says that Inger sounds more like Tom Sawyer than anyone else. I trust Edouard’s judgment, and a girl Tom Sawyer is just the thing. So What Happened to Inger Johanne is my #1 recommendation for middle-school readers.*****

For Older Children

Frontispiece, Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children

The children’s book of the season is Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to his Children. It’s the only unanimous choice on the librarians’ list, and it did sound promising: whatever you think of Roosevelt, he had (according to my childhood reading, anyway) some of the most fun presidential children in history. I was merrily scrolling to get to a letter about Christmas in the White House when I was stopped in my tracks by the words “kill” and “stabbed.” They turned out to be from a 1901 letter to Roosevelt’s twelve-year-old son Theodore III, titled “A Cougar and Lynx Hunt.”

Theodore Roosevelt hunting in Colorado, 1905 (Denver Library Digital Collections)

Theodore (père) is out hunting with his friend Phil in Colorado when their dogs run up a tree after a cougar. Theodore has a clear shot at it, but Phil is taking a picture. The cougar jumps out of the tree, the dogs chase it and get into a big fight, and the cougar

bit or clawed four of them, and for fear that he might kill them I ran in and stabbed him behind the shoulder, thrusting the knife you loaned me right into his heart. I have always wanted to kill a cougar as I did this one, with dogs and the knife.

After that, I just wasn’t feeling the Christmas in the White House spirit. I decided to move on to Literary Digest and “Some of the Seasons [sic] Best Juvenile Books.”

Full-Back Foster by Ralph Henry Barbour: “Describes how a ‘sissy’ is turned into a most serviceable full-back.”

Pass!

The Boys’ Airplane Book by A. Frederick Collins. “It…behooves all ambitious boys to know the mechanism of the airplane, and to be able to construct one which not only will fly but will carry a human passenger….One feels that it would be impossible to go astray under such guidance.”

One would just as soon not test this theory. Pass!

Uncle Sam: Fighter by William Atherton DuPuy. “Describes graphically how we prepared our draft army in the recent war, and how we mobilized our energies efficiently for the most expeditious service to ourselves and our allies. Navy purchases, railroad administration, the minimizing of waste…”

Yawn! And all lies—the U.S. war mobilization was totally inept. Pass!

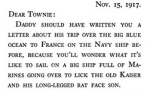

Daddy Pat of the Marines by Lieut. Col Frank E. Evans (U.S.M.C.) “Even the six-year-olds must have their war books.”

Begins thus:

Pass!

Rosemary Greenaway by Joslyn Gray. “The sentimental spirit which pervades this story will be liked by a certain type of girl reader.”

Pass!

The Heart of Pinocchio by Collodi Nipote. The author of the original Pinocchio “is dead, but fortunately another member of the Lorenzini family has skillfully introduced Pinocchio into a story of war.”

Pass!

Joan of Arc by Laura E. Richards. “She has entered more thoroughly into the historical aspects of her heroine than most writers for girls and boys; her sources are carefully noted throughout.”

I’ll stick with Mark Twain. Pass!

These are the best juvenile books? I’d hate to see the worst.

Then I checked out a new edition of Mary Mapes Dodge’s 1865 children’s classic Hans Brinker, or, The Silver Skates, described by Elementary School Journal as a “beautiful gift ed.”

I had thought of Hans Brinker as a middle-grade book. The story turns out to be more harrowing than I imagined, though, with an amnesiac father and a doctor with a dead wife and a missing son. There’s also a scene in which someone draws a knife across a robber’s throat and threatens to kill him. Weary of violence by now, I almost disqualified it. But it has ice skating! And wooden shoes! And the Festival of Saint Nicholas, during which Dutch children become “half wild with joy and expectation”! And tulips! (A footnote about tulip mania quotes from Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.****** You can’t accuse Dodge of talking down to children.)

Not to mention the wonderful new illustrations by Maginel Wright Enright, who turns out to be the sister of Frank Lloyd Wright and the mother of children’s writer Elizabeth Enright, author of Gone-Away Lake and The Four-Story Mistake.

So, finally, a book to recommend to older readers!

Not all children are alike, though. What to give to the kind of child (often a boy) who would open a book, even one as amazing as Hans Brinker, with a wan thank you and a sigh?

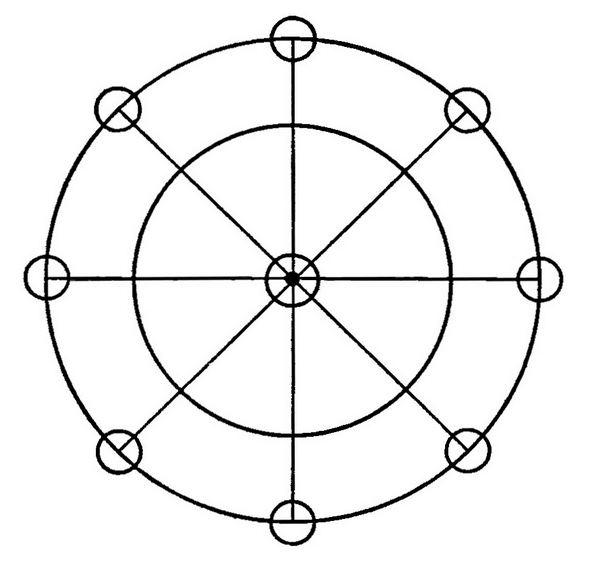

Well, you (and he) are in luck! There’s American Boys’ Book of Signs, Signals and Symbols, by Daniel Carter “Uncle Dan” Beard, a founding figure in American Boy Scouting.******* According to Elementary School Reader, it

explains simply all kinds of signs including danger signs, trail signs, signs of the elements, secret writing, gesture signals, deaf and dumb alphabet, signal codes, railway signals, hobo and Indian signs, and Boy Scout signs and signals.

This book is guaranteed to have your child running outside as soon as the presents are opened to set trail signs and communicate with his friends in steamer toot talk.

(Be forewarned that the book includes swastika-like symbols and hobo signs to note the presence of “white, yellow, red, and black men,” along with some discussion of American Indians that, while intended to be respectful, wouldn’t pass muster today.)

So that’s it—a gift for every kid on our list.

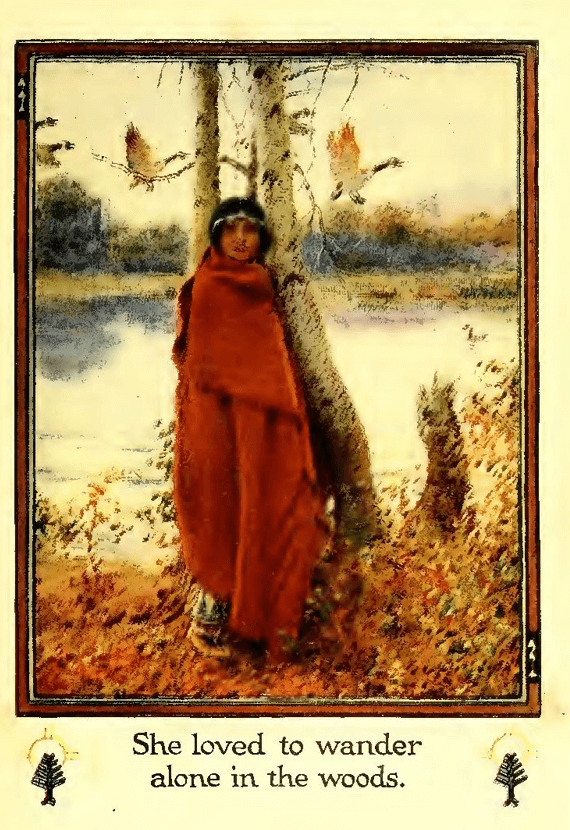

Oh, wait! What about that dreamy teenaged girl who’s longing for a good book to curl up with while her siblings are outside drawing hobo signs?

Henri Matisse, Young Woman in the Garden, 1919

Betty Bell by Fannie Kilbourne sounded promising at first. Moore describes it as “a very readable, thoroughly sophisticated, and well written analysis of a cross-section of Betty Bell at sixteen.” She warns, however, that “we do not recommend the book for children’s reading. In the libraries its title would immediately attract girls from ten to twelve whose mothers would object to it.”

Naturally I immediately downloaded it and started skimming to find the objectionable parts. The book is indeed an exceptionally accurate description of what goes on in an adolescent girl’s brain, but I was soon reminded that inside an adolescent girl’s brain is not a place anyone except the owner of that particular brain would want to spend much time.

Our dreamy young woman would think Betty was an idiot.********

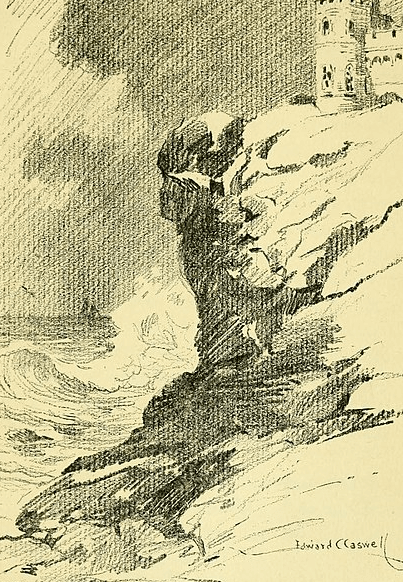

Frontispiece of The Pool of Stars, Edward C. Caswell

There was a lot of buzz around The Pool of Stars by Cornelia Meigs, which Moore calls “a very well-written story.” I remembered Meigs from those lists of Newbery Award winners they were always inflicting on us in elementary school,********* so I spent an hour reading it on my Kindle.

Betsey, our heroine, is agonizing as the book begins about whether to go to college next year or go to Bermuda with her rich aunt, which would (for reasons that are not explained) permanently put the kibosh on college. Studying is so EXHAUSTING, Betsey keeps thinking. All those geometrical shapes and Barbary pirates! I’d rather go to the beach!

I’m starting to suspect that Betsey is not a true intellectual.

She does decide to go to college, though, and spends the rest of the book pondering the mystery of why a young woman living nearby always looks so sad. I. DO. NOT. CARE., I kept saying, before finally giving up.

There’s also Rainbow Valley, the fifth volume in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables series. (Now it’s considered the seventh, but two volumes covering earlier parts of Anne’s life were published in the 1930s.) It didn’t appear on any of the best-of-1919 lists, maybe because it was published late in the year, but, hey, it’s Anne of Green Gables, right?

Except that Anne has, in the two years since Anne’s House of Dreams was published, somehow been transformed from a newlywed (and, by the end of the book, mother of two) to a mother of six who spends all her time thinking about the problems of the town’s new minister.**********

Note to children’s authors: happy newlyweds are one thing, but mothers of six are (to young girls) just squalid.

So what to give to our dreamy girl? In desperation I turned to H.L. Mencken, even though I knew perfectly well that books for girls are not his thing.

And there, miraculously, it was, in a November 1919 Smart Set article called “Novels for Indian Summer.”

The best of them, and by long odds, is “The Moon and Sixpence” by W. Somerset Maugham,

Mencken begins.

It has good design; it moves and breathes; it has a fine manner; it is packed with artful and effective phrases. But better than all this, it is a book which tackles head-on one of the hardest problems that the practical novelist ever has to deal with, and which solves it in a way that is both sure-handed and brilliant. This is the problem of putting a man of genius into a story in such fashion that he will seem real—in such fashion that the miracle of him will not blow up the plausibility of him.

The Moon and Sixpence is the story of Charles Strickland, a middle-aged British stockbroker who abandons his family and goes to Paris and then to Tahiti to pursue his dream of becoming a great artist. He succeeds (the story is based loosely on the life of Paul Gaugin), but at a tremendous cost to those around him, and, ultimately, himself.

Sacred Spring, Paul Gauguin, 1894.

Really? you may be thinking. Your top recommendation for a dreamy teenaged girl is about an egocentric middle-aged stockbroker? Based on the life of a painter who was so reprehensible, even by the standards of 19th-century painters, that the New York Times ran an article last month headlined, “Is It Time Gaugin Got Cancelled?”

All I can tell you is this: I was that dreamy girl, and I loved The Moon and Sixpence.

Happy holiday reading, everyone!

*I pictured Moore and Jordan as bitter enemies, but Moore turns out to have described Jordan as the best librarian-reviewer, which is especially gracious considering that Moore invented the profession.

**Moore mentions, apropos of nothing, that Smith also designed the color poster for Children’s Book Week in 1919, which, as I’ve mentioned, is the first time Children’s Book week was celebrated.

***Fuertes (who was only named after, not related to, famed but racist naturalist Louis Agassiz) was one of the most prolific bird illustrators of his time. Two bird species were named after him, including the Fuertes’s parrot, which is now critically endangered.

American Museum Journal, 1918

****Hale’s brother Edward Everett Hale of “The Man Without A Country” fame clearly got all the literary talent in the family.

*****Note to Norwegian readers (okay, reader): Is this book still famous? And is P-speech an actual thing?

******Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds was written by Charles Mackay, the father of our old friend Marie Corelli.

*******Beard was the founder of the Sons of Daniel Boone, which merged into the Boy Scouts in 1910.

Ernest Thompson Seton, Robert Baden-Powell, and Dan Beard, date unknown

********Much in the way I couldn’t stand the supposedly universally beloved but, to me, vapid heroine of Judy Blume’s Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret.

*********Meigs won for her 1933 book Invincible Louisa, a biography of Louisa May Alcott.

**********Could this have been related to problems in Montgomery’s own marriage to a depressed minister, who, she complained in her diary in 1924, would stare blankly into space for hours with a “horrible imbecile expression on his face”?