One of the (few) disappointments about reading in 1918 is that nothing’s interactive. Of course, I understood when I started this project that my days of discovering what secondary Jane Austen character I most resemble were over for a while.* And I knew that crossword puzzles were a few years away from being invented.

But still, there could be quizzes, or personality tests, or…something. But no. The year peaked with the vocabulary-based intelligence test in the Literary Digest in February. After that, nada. Unless you were a kid, in which case you got to enter St. Nicholas magazine contests, and cut out paper dolls from women’s magazines, and make this actually extremely cool diorama that I am definitely going to get to one of these days.

Delineator, June 1918

Being a grownup, I was left to make my own entertainment. Which I did when I came across this article in the June 1918 Ladies’ Home Journal:

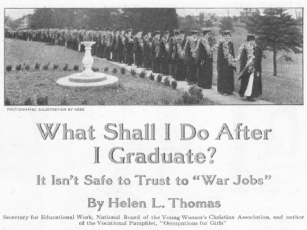

What’s a girl to do, LHJ asks, when the war’s over and the boys come home and want their jobs back? Answer: find yourself a girlier one.

But which one’s for you? LHJ helps you figure it out by providing questions where you match your skills and personality traits with each job.

Which, to the modern sensibility, screams QUIZ. So I added a scoring system and turned it into one.

Here’s how it works: Rank yourself on each attribute. If you have no basis for assessing yourself, estimate how you would score. Add up your points.

Okay, here goes! Get your 1918 pencils out.**

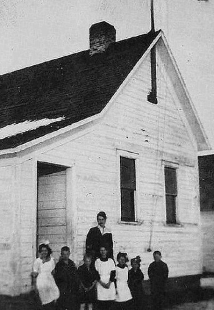

Who Will Make a Good Teacher?

Teacher and students standing next to the Lamoine [Washington] School in 1918 (Library of Congress)

THE GIRL WITH—

Steady nerves (1-5 points) and a sound body (1-5 points).

Clear brain (1-5 points), warm heart (1-5 points), and sympathetic imagination (1-5 points).

Power to build the school into the community (1-5 points).

Enthusiasm for boys and girls that will keep her from becoming a machine (1-5 points).

What Makes a Good Office Worker

American Lumberman, 1907

THE GIRL WHO HAS—

Swift, careful fingers (1-5 points) and an agile brain (1-5 points).

Good eyesight (1-5 points), good hearing (1-5 points), and good memory (1-5 points).

Good judgment (1-5 points) and a sense of responsibility (1-5 points).

The Successful Saleswoman

Loras College, Center for Dubuque History

THE SALESWOMAN YOU LIKE IS—

Alert (1-5 points), courteous (1-5 points, then double your score), and energetic (1-5 points).

Interested in her customer’s needs (1-5 points, then double your score).

Thoroughly acquainted with her stocks (1-5 points).

The Dressmaker and The Milliner

Loras College, Center for Dubuque History

TYPES OF ABILITY REQUIRED—

The seamstress must have skill in hand (1-5 points) and machine (1-5 points) sewing.

The dressmaker needs not only technical skill (1-5 points) but creative (1-5 points) and artistic (1-5 points) ability.

The milliner has need of artistic skill (do not score; included under dressmaker) and business sense (1-5 points).

The sewing teacher should combine technical knowledge (do not score; included under dressmaker) and ability to teach others (1-5 points).

The Broad Field of Domestic Science

Home economics class, Toronto, 1911 (Archives of Ontario)

FOR THE WOMAN WITH—

Skilled hands (1-5 points, then double your score).

A practical turn of mind (1-5 points, then double your score) and the best training (1-5 points).

Ability to command the respect of other people (1-5 points, then double your score).

Got your score? Okay, here’s what, according to LHJ, you can expect from your girl profession. (The assumption being, of course, that you’re white and Christian.)

Teacher

New York Times, July 14, 1918

OPPORTUNITIES FOR TEACHERS—

Teaching is the oldest profession*** for girls outside the home. It offers greater variety of choice to-day than ever before and is especially attractive to the girl with social vision. It is a vocation, not a bread-and-butter job. Salaries are not high, but advancement is certain for the teacher that makes good.

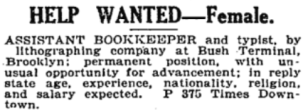

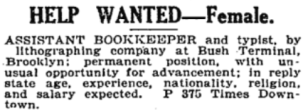

Office Worker

New York Times, July 14, 1918

POSITIONS AND PAY—

Experienced stenographer, $10-25 a week;

Court stenographer, $2000-3000 a year;

Private secretary, $900-1800 a year.****

THE OUTLOOK—

The field is overstocked with half-trained, incompetent stenographers. But for girls with good general education and technical skill there is always room. There are too many $8 a week girls, too few $25 a week ones. For the girl with executive ability, broad education and business experience there are many new openings.

Saleswoman

New York Times, July 14, 1918

KIND OF PERSON IN STORES—

Errand and cash girls;

Cashiers and examiners;

Saleswomen;

Hands of stock and buyers.

WAGES AND CONDITIONS—

The average pay is low, hours long, and the work is not easy, but employment is steady for the competent worker. Hours have been shortened, however, and conditions improved by the activity of the Consumers’ League. Chances for advancement are good, however, for the ambitious girl in the employ of a good firm.

Dressmaker and Milliner

WAGES AND CONDITIONS—

A first-class seamstress or dressmaker is always in demand at $1.50 to $3.50 a day;

The millinery season is short and the hours long. The average milliner needs another trade for the dull season;

The salary for assistant sewing teachers is small, but good for heads of department.

Domestic Science

New York Times, July 14, 1918

SOME OF THE KINDS OF POSITIONS—

Matron or house mother in college dormitory;

Superintendent, purveyor, or dietitian in an institution;

Domestic science teacher in school or Y.W.C.A.;

Manager of a small hotel, summer or all the year;

Visiting housekeeper employed by private families or by the city;

Director of cafeteria, tea, or lunch rooms.

SALARIES—

Teacher, domestic science, $800 and up;

Cafeteria director, $700-1800;

Assistant matron, $200-600, plus board;

Matron, $600-1200, plus living expenses.

FUTURE—

The field of domestic science is not crowded and kinds of positions are multiplying.

I got TEACHER! (30/35.)

Which was a huge relief because, when I took the test before recalibrating it to make the points in each category match up, I got OFFICE WORKER. (27/35 this time around.) Being a court stenographer might be all right, given the interesting crimes I’m always reading about, like painting your pencil a treasonous color and wearing a second lieutenant’s uniform after being discharged for setting your yacht on fire to collect the insurance money. And being a half-trained, incompetent stenographer sounds appealing in a screwball comedy kind of way. But the problem with OFFICE WORKER is that the crucial question is missing: How well would you deal with taking orders all day from a man you’re way smarter than, for a fraction of his pay? I would get a 0 for that.

I got a terrible score in DOMESTIC SCIENCE. (18/35.) Being a matron in a college dormitory might be fun, though. Or director of a tea room. Reading Edna Ferber’s stories rid me of any ambitions I might have had of being a SALESWOMAN (24/35). As for DRESSMAKER (22/35), well, this picture of me in a dress I made in high school says it all:

If I were a middle-class American woman in 1918, I imagine that I would have been a teacher. Probably a pretty happy and capable one.

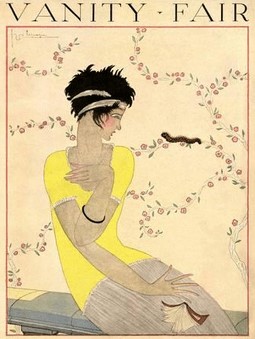

Or maybe I would have gone for a war job, like this one.

New York Times, July 15, 1918

Or this one—big enough for any intelligent man!

New York Times, July 15, 1918

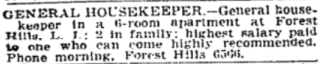

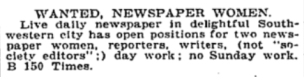

Or—top choice—one of these.

New York Times, July 15, 1918

(All of these jobs were advertised in the “Help Wanted – Female” section—there were no gender-neutral want ads.)

Judging by what happened to most women, though, I’m not optimistic about my chances of hanging on after the men came home. It’s lucky, then, that I’m living a time when women can be diplomats. And late-in-life creative writing students. And time-traveling bloggers.

So…what’s YOUR 1918 girl job?

* The insipid Captain Benwick from Persuasion. Which is crazy. I’m totally Jane Fairfax.

** Don’t worry, I checked, and pencils weren’t made of lead back then, or ever. The reason we call the graphite in pencils lead is that graphite was mistaken for lead when it was first discovered.

*** “Oldest profession” struck me as an unfortunate choice of words, so I did a Google NGram,

which showed that this phrase has only been around since—about 1918, actually. I did some research (okay, looked on Wikipedia) and found that the phrase began making its way into the language after Kipling referred to “the most ancient profession” in an 1889 short story. This is the kind of discovery that makes all those hours of photo file size reduction worthwhile for the weary blogger.

**** A surprising omission from this list is bookkeeper. A lot of women had this job, including my grandmother (on my mother’s side–it was my grandmother on my father’s side who may have marched with the Czechoslovakians in the July 4 parade).