Two months into My Year in 1918, I feel like I used to feel two months into a Foreign Service posting: completely at home in some ways but totally bewildered in others. I know who Viscount Morley was*, and which author every critic trots out to bemoan the sad state of fiction**, but there are references that go right over my head. Who is Baron Munchausen? What is Fletcherizing? And the jokes. I’ll never get the jokes.

Best magazine: The Crisis

This is a repeat, but no other magazine approaches The Crisis in terms of quality of writing and importance of subject matter. Aside from W.E.B. Du Bois’ autobiographical essay, which I wrote about last week on the 150th anniversary of his birth, the February issue includes Du Bois’ scathing take-down of a government-sponsored study on “Negro Education” that advocated the replacement of higher education institutions with manual, industrial, and educational training. There’s a horrifying account of the mob murder of an African-American man in Dyersburg, Tennessee—so brutal, the magazine reports, that some white townspeople felt he should have had a “decent lynching.” On the literary side, there’s “Leonora’s Conversion,” a slight but engaging story about a wealthy young black woman’s brief flirtation with the church.

I’m not awarding a Worst Magazine this month. Good Housekeeping was a contender again—dialect-talking black maid Mirandy has the month off, but Japanese manservant Hashimura Togo*** expounds on his employer’s marital problems in equally fractured English. (“‘You have left off kissing me as usually,’ she dib. ‘O.’ He march and deliver slight lip.”) The magazine redeems itself somewhat, though, with an article by suffragist Anna Kelton Wiley called “Why We Picketed the White House.”

Best short story: “A Sordid Story,” by J., The Egoist

February wasn’t a great month for short stories. Most of the ones I read, including two that made it into The Best American Short Stories of 1918, started out promisingly but ended with pathos or a gimmicky twist. “A Sordid Story,” in the January**** Egoist, isn’t great literature, but it has daring subject matter and lots of atmosphere. It features a Cambridge student named Alphonse, whose life is described in the most British sentence I’ve ever read:

He made friends easily and took friendship seriously; so seriously that he spent nearly the whole of the Michaelmas term following the taking of his degree in reading Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound and The Gospel according to St. Luke in the Greek with a much younger man—a certain Roderick Gregory—who was in his second year, but had hitherto failed to pass his Little-Go.

Alphonse falls for Roderick’s sister Beatrice, who “used to have a pet pig, and she called him Shakespeare, because he would be Bacon after his death.” But he spends the night with a working-class girl who grabs his arm as he’s walking near Midsummer Common and says, giggling, “Can yer tell me what o’clock it is?” Horrified with himself the next day, he goes back to her lodgings to pay her off. She tells him that he was her first lover, then, when he tells her it’s over, says, “Yer weren’t the first, then!” Relieved “not to be the first to help send a woman downward,” he goes back to his rooms, where Roderick is playing the cello and twenty-five copies of the Quarterly Journal of Mathematics, in which he has published a paper, await him. It’s only years later that he figures out that he was, in fact, the first.

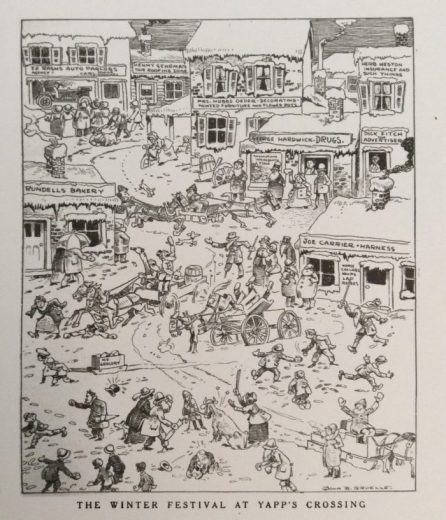

Worst short story: “A Verdict in the Air,” J.A. Waldron, Judge

Harwood, on leave from aviation training, goes to a cabaret in Chicago. To his surprise, one of the singers is his childhood sweetheart Bessie Dean, who left their Ohio hometown to pursue a career in opera. She introduces Harwood to her husband Grindel, who takes a dislike to him. A few days later, Harwood is training on the Pacific Coast, when who should show up as a mechanic but Grindel! Harwood has a series of flying accidents, and Grindel is suspected, but he goes AWOL. Harwood is sent to fight with the French army. He visits a friend at a field hospital, where the nurse is none other than Bessie, who has escaped her husband. Back at the front, there’s a heated battle. Harwood pursues the last remaining German plane and hits its rudder after a lively skirmish. As the plane plunges to the ground, he sees that the pilot is—you guessed it—Grindel!

Well, the illustration is kind of cool.

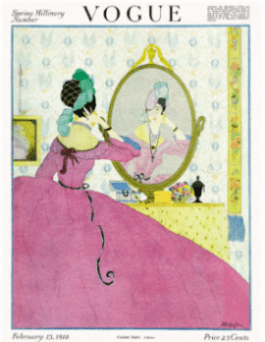

Best magazine covers:

February was a great month for magazine covers. I just wish that the insides of the magazines were half as good. Besides the ones from Harper’s Bazar and Vanity Fair that I’ve mentioned already, there’s this Helen Dryden cover from Vogue,

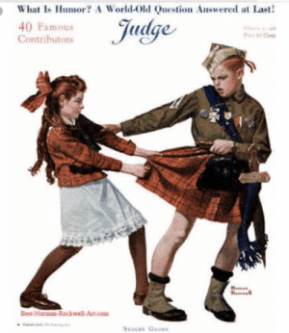

and this one, which Norman Rockwell sold to Judge after the Saturday Evening Post turned it down. I can kind of see why.

Best joke:

This isn’t exactly a joke, but it made me laugh. It’s the opening of Louis Untermeyer’s review of poetry collections by Edna St. Vincent Millay, Samuel Roth, and Edwin Curran in the February 14 issue of The Dial.

These three first volumes, with their curious kinship and even more curious contrasts, furnish a variety of themes. They offer material for several essays: on “What Constitutes Rapture”; on “The Desire of the Moth for the Star”; on “The Growing Tendency among Certain Publishers to Ask One Dollar and Fifty Cents for Seventy Pages of Verse”; on “A Bill for the Conservation of Conservative Poetry”; on “Life, Literature, and the Last Analysis”; on “Why a Poet Should Never be Educated.”

The Growing Tendency among Certain Publishers to Ask One Dollar and Fifty Cents for Seventy Pages of Verse! That Louis Untermeyer is such a card!

Not amused? Okay, then, you go back to 1918 and try to find something funnier.

Worst joke:

Once again, hard to choose. Maybe this, from the February 9 issue of Judge:

“You don’t—know me, do you, Bobby?” asked a lady who had recently been baptized.

“Sure I do,” piped the youth. “You’re the lady what went in swimming with the preacher, last Sunday.”

On to March!

*A British diplomat

**Mrs. Humphrey Ward

***Really Wallace Irwin, who made a career of writing about Togo. Mark Twain was a fan.

****I was reading The Egoist a month late on the principle that it would have taken time for the magazine to get to the United States, which I’ve since decided is ridiculous.