The podcast on children’s books that I’ve been cohosting since May has been taking up all of my social media energy, but I’ve finally gotten sufficiently on top of it to return to the world of 100 years ago and revisit San Francisco, where I spent a few days in July.

Like everyone else, I’d heard the horror stories about what’s happened to the city, which I had last visited in 2004. Since my trip, I’ve seen some articles along the lines of “it’s not really as awful as they say,” or at least “it’s more complicated,” but at the time my expectations were along the lines of “urban hellscape.”*

So, as I strolled with my husband around neighborhoods like Nob Hill, North Beach, and Chinatown, I was pleasantly surprised to see a totally normal city. Not a utopia, but the same mix of commerce, bustle, and urban problems that I’m used to in Washington, D.C. If tourists were staying away in droves, no one had told the throngs of people at Fisherman’s Wharf or on the twisty-turny street.

After a week in Sacramento, with its downtown full of empty storefronts and sidewalks empty of people aside from the homeless, San Francisco seemed positively vibrant.**

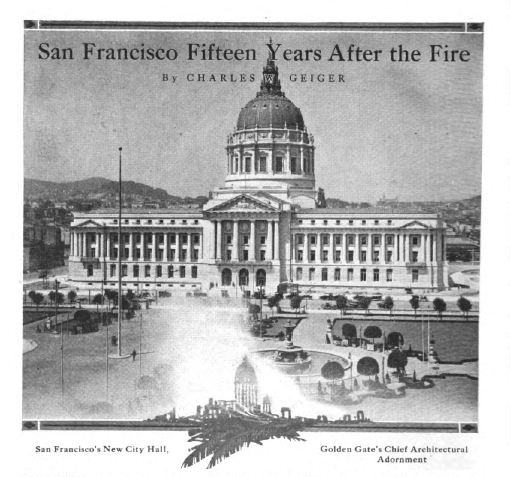

On the bus from Sacramento to San Francisco, I had prepared for my visit by doing some reading from 100-year-old magazines. In an article in the January 1922 issue of Illustrated World called “San Francisco Fifteen Years After the Fire,” Charles Geiger recounted the city’s impressive recovery following the 1906 earthquake and subsequent fires that destroyed much of the city. “When one gazes about and observes the new and beautiful city of San Francisco, which fifteen years ago was a barren desolate waste following the catastrophe which befell it,” Geiger wrote, “he is filled with admiration for the bravery and the daring of the people of this great western city who at a cost of half a million dollars have made a remarkable record of achievement.”

The most notable of these achievements, Geiger says, is the reconstruction of the Civic Center, which includes the City Hall, the city’s “chief architectural adornment,” the Exposition Auditorium, and the Public Library.

I couldn’t wait to check out this marvel of civic rebirth. My husband agreed to come along. I would have felt more comfortable with a Lonely Planet guidebook, with maps orienting you by neighborhood and text warning you of dangers. Bookstores in San Francisco turned out to be surprisingly few and far between, though. I did go to the legendary City Lights Bookstore in North Beach, but when I asked the young man at the checkout if they had guidebooks he looked at me like I’d asked for the Colleen Hoover fanfiction section. Guidebooks for where, he asked.

“San Francisco,” I confessed, unmasked as a tourist.***

“There might be some over there,” he said, pointing to a nearby shelf. And there were a few, but they were all along the lines of A Guide to San Francisco’s Ghosts. I didn’t want a visitation from the dead! I just wanted to go to City Hall!

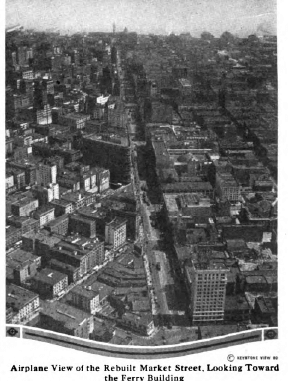

So, on a Saturday morning, I put City Hall into Google Maps and got a route that went through Union Square and along Market Street. That sounded okay. Market Street was famous, right? Plus, I’d read on a blog post that one of the best bookstores in San Francisco was in the area.

Union Square was buzzing. Tourists and locals were enjoying the beautiful weather and pouring in and out of stores and restaurants. We continued along Market Street.

It didn’t take more than a block or two for us to see that something was very, very wrong. Since it was a weekend, I wouldn’t have expected a lot of foot traffic in this downtown area, but it didn’t seem like anyone came here, ever, other than the people standing around on the sidewalks, seemingly on drugs. We didn’t feel threatened, exactly. We just felt uneasy, like we had entered some postapocalyptic landscape. I don’t have any pictures. It wasn’t a place where you wanted to stand around messing with your phone, and, in any case, how do you photograph nothing? Suffice it to say that the wasteland of empty glass buildings didn’t at all resemble this photo of the area in Illustrated World.

Fortunately, it didn’t take long to get to the Civic Center area, which, while not exactly bustling, at least showed signs of life. Kids played at a playground in the square, and I wasn’t the only tourist snapping photos of City Hall.

The buildings Geiger had marveled over resembled their 1922 selves, although the new public library he wrote about is now the Asian Art Museum.

The current library, which opened in 1996, is nearby, and we paid a visit. It was a pleasant space, though fairly empty on this sunny Saturday.

The bookstore, disappointingly, turned out to be a corner of the library where used books were for sale. No Lonely Planets here. I was ready to get out of Civic Center. Let’s go to Haigh-Ashbury, I said to my husband, and put the address of a highly recommended bookstore in that neighborhood into the Uber app.

When we got to the address, though, there was no bookstore to be found. I was starting to take this personally. Luckily, it turned out that the store—The Booksmith—had recently moved a block or so down Haight Street. I spent a happy hour browsing, and added The Booksmith to my list of favorites. And I finally got my Lonely Planet, which belatedly warned me that the Civic Center area is “best avoided without a mapped route to a specific destination.”

The rest of the trip was more reminiscent of 1960s than 1920s San Francisco. We chatted with tie-dye-dressed servers at a Haight-Ashbury creperie, who told us about the throngs the previous week, when the Dead had been in town, watched drummers drumming on Hippie Hill in Golden Gate Park,

and visited Berkeley, a first for me.

I took in some sensational views, praise that we Cape Town residents do not dish out lightly.****

Outside the Fairmont Hotel on Nob Hill, there’s a statue of Tony Bennett, who first sang “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” there in 1961. He had died a few days before we arrived, and I stopped by twice to look at the floral tributes. Both times I saw a young hotel employee—maybe the same one, but I’m not sure—sadly paying his respects.

A few days after we left, I learned that, on August 2, 1923, a hundred years minus a week before our visit, Warren Harding had died at San Francisco’s Palace Hotel. The hotel, built in 1909 after the 1875 original burned in the fire, is still there. It’s on Market Street, in a less desolate area than where we walked. If I’d been more up on my history, I could have paid a visit.

Oh, well. If I was going to memorialize someone, I’d pick Tony Bennett over Warren Harding any day.

As for San Francisco’s future, it would be tempting to loop back to Geiger’s glowing account of the city’s rebirth and say, “If they could rebuild then, they can rebuild now.” A closer look at the reconstruction, though, reveals that, while impressively rapid, it was marred by corruption, violence against alleged looters, and an attempt by city leaders to move residents of Chinatown, which had been destroyed by the fire, to mud flats on the outskirts of the city.

I did find one source of inspiration: the Chinese community, along with Chinese government representatives, successfully fought the relocation plan. Chinatown was rebuilt, with the new buildings featuring architectural flourishes like pagodas and dragons that still define the neighborhood today. It was a local businessman named Look Tin Eli who had the idea for the design of the new buildings, but some critics have called them a fantasy of China by western architects aimed at turning the neighborhood into a tourist attraction. Still, the community activism, business acumen, and resilience that led to Chinatown’s rebirth is a story I’m glad to have learned about.

*Heads up that these articles are from the New York Times and New Yorker, respectively. Both publications have a monthly quota of free articles for non-subscribers. I’m a Times subscriber, but it always irritates me when I unknowingly click on a link to a New Yorker article and belatedly realize that I’ve used up one of my six articles.

**Of course, Sacramento might have been more vibrant if the state legislature had been in session and/or temperatures hadn’t been hovering around 100. Also, a shout-out to the wonderful downtown bookstore Capital Books.

***Except who really cares? I’ve never understood why you’re supposed to be embarrassed about being a tourist, assuming you’re acting like a normal person and not an ugly-American stereotype, in which case you probably wouldn’t be embarrassed anyway. Is everyone just supposed to stay in the place they come from all the time to avoid this shameful label?

****If you’re new to this blog and thinking, “But you just said you live in Washington, D.C.,” I spend part of the year in each city.

New on the podcast, Rereading Our Childhood:

Rereading The Owl Service by Alan Garner

Rereading The Great Brain by John D. Fitzgerald

Rereading A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle