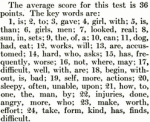

My quest to earn a 1919 Girl Scout badge (here and here) got my competitive juices flowing. And what’s more competitive than an intelligence test? I set out to track one down.

Last year, I could only find one intelligence test from 1918. It equated intelligence with vocabulary, because of course familiarity with this

and this

isn’t class-dependent AT ALL. I did pretty well, scoring in the Superior Adult range.*

By 1919, magazines were full of intelligence tests. A test called the Army Alpha had been widely used on American soldiers during the war, and psychologists and business leaders were eager to use ability testing in civilian life. I settled on a bevy of tests in the March 1919 edition of American Magazine.** “Try these tests on yourself and others,” the magazine urges us, although, in my experience, the “others” tend to flee.

Tests like this are, we learn in an accompanying article, completely scientific—it’s possible to give a job applicant or a soldier a set of tests that will accurately predict his job success. (“His” being the operative word. No one’s wasting time testing women’s intelligence.)

In the past, American Magazine tells us, soldiers were sorted into units based on where they lived rather than by skills. So, during the Civil War, all the men from one neighborhood would be assigned to the remount squad (the unit responsible for supplying horses), when it would have made more sense to staff it with people who know something about horses.

When the United States entered World War I, some psychology professors were convinced that there must be a better way. They came up with

three great developments which have been not only factors in victory but will be of enormous importance to business, now that peace is here. They are:

- The Qualification Card

- The Intelligence Test

- The Rating Scale

The Qualification Card is, like it sounds, a card with a soldier’s qualifications listed on it. When the pipes froze at a military base, all of the plumbers in town were out on calls, so

in desperation, the quartermaster telephoned the Personnel office:

“Have you any plumbers on the list?”***

“How many do you need?”

“Forty or fifty.”

“We’ll send you a hundred,” said the Personnel officer. And in less than an hour he had done so.

This scheme makes sense, although I don’t see why it required a team of brainiacs to come up with it.

The Intelligence Test and Rating Scale, are, American Magazine assures us, equally useful.

Take a hundred men in the same line of business, whose incomes vary widely, and give the same tests to all of them. If, generally speaking, it rates them in about the same order in which the judgment of the business world has rated them, then the test is pretty likely to be a good one.

So the test is accurate because people who make more money do better. Logic doesn’t get more airtight than that!

The Tests

On to the tests! They work best on paper, and you can download and print them out from the magazine. (Hit “Download this page (PDF)” in the box to the left of the text.) If you can’t be bothered, you can do most of them by looking at the questions on the screen. The answers, where needed (most are self-evident), are provided below.

TEST 1

TEST 2

TEST 3

TEST 4

(On #14, note that there are two spaces between “beggar” and “money.”)

TEST 5

That’s it! Put down your pencils.

The Answers (and My Results)

TEST 1

The answers are self-evident, but here are my 3’s, x’ed out in pink, in case you missed some:

The first time I took this test, I got 2 minutes, 23 seconds. This is well into the Poor range, which starts at 88 seconds. I took it again and was almost at the 3-minute mark when the phone rang, putting me out of my misery.

I tried to come up with justifications for my sorry performance. The 3’s look so much like 8’s! Especially this one with a line through it (sixth row, fifth column),

which cost me about ten seconds.

Then it occurred to me that the numbers, when printed out on standard printer paper, are way smaller than they would have been in the magazine. I copied them into a Word document, enlarged them, and got 2 minutes, 10 seconds. I put them into landscape mode and stretched them out even bigger. 2 minutes on the dot, still well within the Poor range. I gave up.

This didn’t come as a huge surprise. Rapid visual processing is not my forte. I would, I accepted long ago, be the world’s worst air traffic controller. But there are lots of tests to go!

TEST 2

There are no answers provided, but they should be self-evident—speed is the issue here.

Words are much more my thing, and I did well: 19 seconds, two seconds into the Excellent range. Feeling better!

TEST 3

Again, no answers needed.

I’m better at dealing with numbers when they’re not hiding in a jungle of other numbers. I remembered eight numbers, in the Good range.

TEST 4

American Magazine doesn’t provide answers, but I found the same exam in the April 1926 issue of Popular Science, with answers. Here they are:

Add up the number of words you got right for your score. (This isn’t exactly fair, because the 1926 test imposes a four-minute time limit, but, well, life isn’t always fair.)

Here are my answers:

I got 51 out of 69, well above the average score of 36, and bumped it up to a 53 because of confusion about the beggar sentence. But I’ve got some serious issues.

#10, “She ____ if she will,” is the only one that truly stumped me. After considerable thought, I wrote “knows.” I wasn’t thrilled with this, though, because “she knows whether she will” would be better syntax. The actual answer? “She CAN if she will.” Which made no sense to me until I figured out that “will” is being used in the sense of “wants to.” This struck me as archaic even for 1919.

A Google search for “she can if she will” comes up with this quotation from Roderick Hudson, an 1875 Henry James novel that I never heard of:

You see, Roderick, a young, impoverished sculptor studying in Rome, is engaged to Mary back home, but he falls in love with Christina, and Rowland, his patron, is in a quandary because he’s in love with Mary himself but feels obliged to break up the Roderick/Christina liaison because, well, I’m not sure why.

Never mind. My point is, just because someone says something in a Henry James novel doesn’t make it normal.

Then there’s #7, “The poor baby ______ as if it were ________ sick.” I wrote, “The poor baby cried as if it were very sick.” The “correct” answer: “The poor baby looked as if it were real sick.”

REAL sick? That’s just wrong. And, I was convinced, was just as wrong in 1919. Looking for examples of this usage from that era, I found this semi-literate letter, which was, for some reason, entered into the record of the Senate Select Committee to Investigate the Election of William Lorimer in 1912.****

Other answers just seem arbitrary. Like #20, where I say “When one feels drowsy and tired…” and the “correct” answer is “When one feels drowsy and sleepy…” Either way, you’re using a pair of redundant adjectives.

But everyone else is presumably being judged by the same capricious standards, plus I had that time advantage, so I’ll stop quibbling.

TEST 5

There are no official answers, but they’re easy to figure out once you remove the time constraint. Here are mine:

I had fun with this one. It engages your mind and is tricky in the best way. At 101 seconds, I fell into the Good category. Shaving off a couple of seconds for setting and shutting off the timer bumped me up to Excellent.

Except—what’s this?

A horse has HOW MANY feet? What was I thinking? Even given my dubious grasp of animal physiology, I know better than that. I was trying to go too fast, that’s my problem. I could argue that it says fill in a number, not the correct number, but that’s grasping at straws.

The quiz doesn’t say how to score yourself if you get something wrong, but this is a definite fail.

So, bottom line:

TEST 1 – Poor.

TEST 2 – Excellent.

TEST 3 – Good.

TEST 4 – No categories, but I say Good.

TEST 5 – Poor.

There’s no overall scoring system, but if you scale Poor at 1, Fair at 2, Good at 3, and Excellent at 4, I average out at exactly 2. You can’t get more mediocre than that.

So What Does it All Mean?

To buck myself up, I turned to the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature, 1919-1921. Maybe I could, among the dozens of articles on intelligence tests, find one saying that they’re a bunch of nonsense.

And I did!

To wit, an article in the May 10, 1919, Literary Digest called “Flaws in ‘Intelligence Tests,’” excerpted from Engineering and Contracting magazine. Halbert P. Gillette, the magazine’s editor, says that

an engineer, being trained to use mathematics, knows that before he can calculate the combined effect of different energies, he must reduce them to a common unit. He knows that one hundred horse-power plus ten British thermal units per second does not make 100 units of any kind whatsoever. Yet the same engineer will probably read, without criticism, an article in which a military officer is ‘rated’ thus:

Physical qualities…………….……….9

Intelligence……………………….……..12

Leadership…………………………….…15

Personal qualities……….…….…….9

General value to the service….24

—–

Total rating in scale of 100 69

Comparing men (them again!) by “adding” up their different qualities, Gillette concludes, is nonsense.

Some such calculation of the relative number of mental units in ‘character’ and in ‘knowledge’ may possibly be made by psychologists a century hence, but not until that is accomplished will it be rational to rate ‘character’ at twenty-four and ‘knowledge’ at fifteen. Any such rating is nonsense.

These five tests are all about intelligence, but they measure very different types of mental ability. So maybe I shouldn’t worry. Maybe I should let the people who excel at finding 3’s be air traffic controllers***** and content myself with doing things that people who excel at shouting out antonyms are good at, like writing blogs about 100 years ago.

Plus, I reassured myself, there’s still my Superior Adult rating on last year’s vocabulary-based intelligence test.

Except that Gillette pooh-poohs that test as well. “It is claimed to give results approximating those obtained by applying the Binet-Simon psychological tests,” he says. (IQ tests, that is.) “But if the Binet-Simon tests are not satisfactory, the vocabulary tests cannot be more so.”

Oh, right. Good point.

Gillette is worried about Columbia University’s plan to use ability tests, rather than tests of general knowledge, as entrance exams. “To put it mildly, this is a radical experiment,” he says.

Gillette seems like a sensible guy. He might be disappointed that, in the “century hence” he ponders, we haven’t developed more accurate measures of intelligence. And he’d no doubt be appalled that we use standardized tests that correlate highly with wealth as a gateway to higher education—although now it’s your parents’ money, not yours, that counts.******

Still, I’ll never be able to resist an intelligence test. As I mentioned, there are lots more out there. Next time, I swear, I’ll know how many feet a horse has.

In the meantime, let me know if you have better luck than I did tracking down those pesky 3’s!

*Apparently there are lots of other test-taking fans out there—this ended up being my most popular post of 2018.

**American Magazine has an interesting history. It rose from the ashes of several failed magazines in the Leslie empire in 1906 and became the home of muckraking journalists like Lincoln Steffens and Ida Tarbell. By 1919, it was a general interest magazine. It folded in 1956.

***I’ve often wondered whether people actually talked in this inverted way or if it’s just a journalistic/literary convention.

****Lorimer, a Chicago politician known as the “Blond Boss,” was eventually booted out of the Senate for vote-buying in the state legislature. This was right before the ratification in 1913 of the Seventeenth Amendment, which provided for election of senators by the popular vote, making it more expensive, though still possible, to buy elections. A lot of people in Chicago thought that Lorimer’s ouster was politically inspired, and there was a parade for him on his return.

*****Which wasn’t a job in 1919 but would become one in 1920, when Croyden Airport in London pioneered commercial air traffic control.

******Less so than in the past, though. More and more colleges are making standardized tests optional for undergraduate admissions. Princeton, my graduate alma mater, recently announced that 14 of its departments will, in the interest of diversity, no longer require the Graduate Record Exam.

One thing I remember clearly from a graduate Educational Psychology class at Stanford in 1967: Intelligence is “that which is measured by an intelligence test.” Enough said?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said!

LikeLike

It’s fun to see these hundred-year-old intelligence tests. There was so much excitement about the potential of testing back then.

LikeLike

I agree! Today we focus (rightly) on the inequities of intelligence testing, but it was motivated at least in part by the desire to create a meritocracy.

LikeLike

It’s interesting how there are sometimes unintended consequences, and things don’t always play out as anticipated.

LikeLiked by 1 person