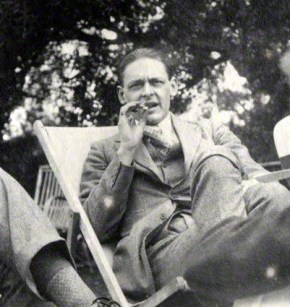

Christopher Morley was one of those famous-in-their-time people no one has heard of today.* In 1918, the hardworking twenty-seven-year-old had just published Parnassus on Wheels, his first novel, and a book of light verse called Songs for a Little House,** and he had a book of essays coming out. He was also the literary editor of Ladies’ Home Journal.

In a piece in the February 1918 issue of The Bookman (originally published in the New York Sun), Morley stirred up quite a kerfuffle. The issue: what books you should choose for your guest room. “Let us assume that many of your guests are of the male sex and have the habit of reading in bed,” he writes. “You keep a reading lamp by the bed, of course, and a bookshelf. What thirty volumes would you choose to fill that shelf?”

Of course, Morley doesn’t really want to know what books YOU’D choose. He wants to tell you what books HE’D choose. As advertised, they’re pretty manly. Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, Joseph Conrad, Rudyard Kipling. Plus some manly-sounding books I never heard of, like The Adventures of Captain Kettle and Casuals of the Sea. You can read the rest of the list here. Morley writes that

I find that for such strollers, wastrels and errant persons as frequent my house, this is a fairly well-selected guest-room library. I wonder if your readers will concur.

They didn’t. Harold Crawford Stearns sent in a list, published in March, that only had one duplicate with Morley’s, the Bible. It was equally manly, though. In April, D.M.T. Willis argued that Morley had chosen not bedtime books but “books that one wants to read when wide awake on a cold afternoon before the fire, or in a hammock under trees in warm weather.”

Bedtime reading, he says,

seems to me like the intense desire to eat candy one experiences immediately after church service, a sort of reactive indulgence, a kind of “now-I-can-do-as-I-please-for-the-rest-of-the-night” feeling.

My sentiments exactly!

Willis includes little blurbs with his list, like, “The Rubaiyat. Because every man and most women sometime at night want to feel as happy-go-lucky and sentimental as Omar,” and “The Bible, because some one might read it and become a poet.” His list is as lacking as Morley’s in women authors, but he’s such a charming blurber that I would totally stay at his house.

As for the contribution from Edward O’Brien, the editor of the Best American Short Stories series, all I can say is, really, Edward? The Canterbury Tales? At bedtime? I checked out another one of his choices, Religio Poetae, by Coventry Patmore. Here’s how the title essay starts:

No one, probably, has ever found his life permanently affected by any truth of which he has been unable to obtain a real apprehension, which, as I have elsewhere shown, is quite a different thing from real comprehension.

Zzzzzz.

The Bookman, to its credit, is snarky about Morley’s gender policy, saying in April that

Mr. Morley’s guest-room is apparently adapted solely to the needs of his male friends—or is it that his women visitors are of the kind that do not read?***

Finally, some women, identifying themselves as “Two Old Maids,” weigh in, and at last we have a handful of women authors: Jane Addams, Edna Ferber, and Lady Montagu.

Of course, I’m just like Christopher Morley: the real reason I’m writing about this is to give you MY 1918 guest room bookshelf list.

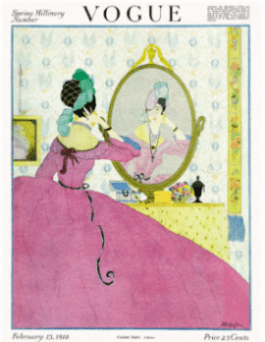

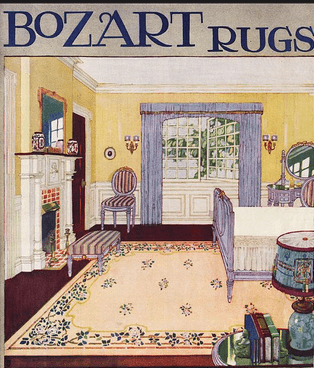

First I need a 1918 guest bedroom, though. Luckily I found one that’s perfect:

Ladies’ Home Journal, May 1918

Okay, now for my list. It includes a mix of books I’ve read for this project, other 1918-era books I’ve been wanting to read, and a few earlier classics. In the spirit of D.M.T. Willis, I’ve included blurbs explaining why I picked each one.

- Bab: A Sub-Deb by Mary Roberts Rinehart. Because this story about a rebellious, hapless teenager is hilarious, and short enough that you’ll be able to read the whole thing during your visit.

- Emma by Jane Austen. Because somehow it seems more 1918-ish than the rest of Austen.

- Mrs. Spring Fragrance by Sui Sin Far. Because I just finished this fantastic collection of short stories about the Chinese community in Seattle and San Francisco, and I can’t wait to tell you about it.

- The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton. Because being a houseguest with a well-stocked bookshelf at hand is such an Edith Wharton thing to do.

- The Magic City by E. Nesbit. Because every guest room bookshelf needs some magic, and I missed this one during my E. Nesbit years.

- Tendencies in Modern American Poetry by Amy Lowell. Because I want to take a deeper look into what was happening in poetry in 1918, and who better to explain it than Lowell?

- The Tree of Heaven by May Sinclair. Because it was one of the big books of 1918, but when I ordered a print-on-demand version they sent me a book with Sinclair’s name on the cover but a 1907 Robert Chambers book with the same title inside.

- Pointed Roofs by Dorothy Richardson. Because May Sinclair said in The Egoist that she’s a great modernist but I’d never heard of her.

- Villette by Charlotte Brontë. Because I’ve been wanting to read it and it seems more bedtimey than Jane Eyre.

- Renascence, and Other Poems by Edna St. Vincent Millay. Because Louis Untermeyer panned it in The Dial and I’m in the mood to pick a fight.

- Marion: The Story of an Artist’s Model by Winnifred Eaton. Because the story of a half-white, half-Chinese artist’s model sounds intriguing, plus she’s Sui Sin Far’s sister.

- Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery. Because, shamefully, I’ve never read it.

- Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster. Because this breezy epistolary novel, which I wrote about here, is the perfect bedtime read.

- Personality Plus by Edna Ferber. Because the Two Old Maids sound like they know what they’re talking about.

- O Pioneers! by Willa Cather. Because it’s one of the best books I’ve ever read. Just don’t read the ending right before you turn off the light, like I did.

- The Last Ditch by Violet Hunt. Because her wonderful poem in Poetry magazine about her breakup with Ford Madox Hueffer (Ford) made me want to read more of her work.

- The Story of an African Farm by Olive Schreiner. Because I really need to read this South African classic.

- Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House, by Elizabeth Keckley. Because Keckley’s amazing journey sounds well worth reading about.

- The Circular Staircase by Mary Roberts Rinehart. Because this was Rinehart’s first best-seller, and if her mysteries are as good as Bab: A Sub-Deb I can’t wait to get started.

- Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher. Because I read this when I was very young and I’d love to see if I remember anything.

- The God by H.D. Because I need to start actually reading the Imagist poets instead of just reading about their love lives.

- Married Love by Marie Carmichael Stopes. Because, who knows, this British sex manual might come in handy for my houseguests.

- Parnassus on Wheels by Christopher Morley. Because Jeff O’Neal raved about it, but mostly because I love the idea of Morley sitting on the bookshelf with all these women.

Of course, what I’ve really done is put together a list of books I want YOU to have when I stay in YOUR guest room. I’ll be traveling a lot over the next few months, so get ready!

(And there’s still room on the bookshelf–I haven’t reached Morley’s 30 volumes yet–so I’d welcome your suggestions.)

*Except for Jeff O’Neal of Book Riot, who talked about Morley’s novel Parnassus on Wheels on last year’s holiday book recommendation podcast.

**It’s just like it sounds. He writes so goopily about his wife that I assumed, based on previous 1918 experience, that she would run off with a female Imagist poet in short order. But no, they were still married when he died in 1957.

*** This can’t possibly mean what it sounds like. If it did, she wouldn’t be sleeping in the guest room, would she?