I realize that it’s unreasonable to sign up for the annual meeting of the International T.S. Eliot Society, followed immediately by the T.S. Eliot International Summer School, and complain that people talk about T.S. Eliot too much. I became a member of the T.S. Eliot community in a roundabout way, though, my lifelong but low-key interest in his poetry having being reinvigorated when I encountered his early poems and criticism in “real time” during my year of reading as if I were living in 1918. The society’s annual meetings were online during COVID, which seemed like a low-investment way to dip my toe into Eliot studies. Next thing I knew, I was attending the 2022 summer school in London, followed by in-person conferences in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and St. Louis, Missouri. In real life, I’m way more interested in Eliot than anyone else I know (as my loved ones occasionally gently remind me), but the Eliot community is, to put it mildly, not real life. Sometimes, a few days into a conference, I walk into a room, hear it buzzing with, “T.S. Eliot, T.S. Eliot, T.S. Eliot,” and think that there must be more to life.*

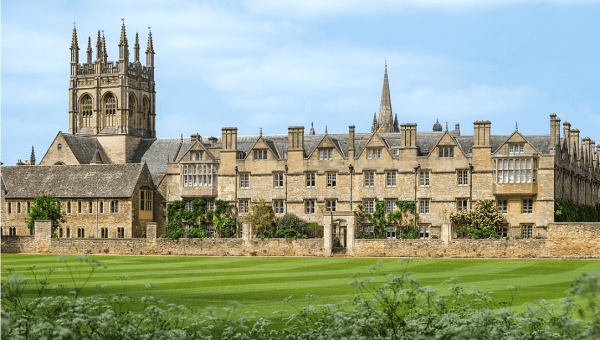

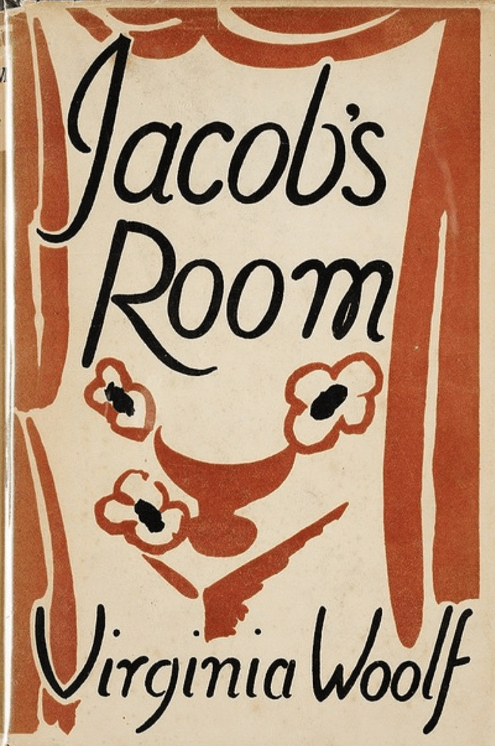

I was excited, then, to see that among the the seminars on offer at this year’s summer school, which is taking place this week at Merton College, Oxford, was one on Eliot and Virginia Woolf. As an added bonus, it was taught by one of the most interesting and fun young Eliot scholars (a surprisingly competitive category). I’ve always had a vague interest in Woolf. I read To the Lighthouse for AP English in high school, read her first novel, The Voyage Out, as part of this project, read her essay “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” twice in recent years for reasons I can’t remember, and read her long feminist essay “A Room of One’s Own” somewhere along the way. (Recently I realized, aghast, that I have never actually read Mrs. Dalloway.) I wanted to read more of Woolf’s work, but I needed a kick in the pants, which I got with this seminar: the main texts were Eliot’s The Waste Land and Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, both published in 1922.

Fate had other ideas, though. The morning after I arrived in Dublin, a few days early for the annual meeting at Trinity College, I woke up with a fever and tested positive for COVID. This entailed five days of isolation in my dorm room, followed by a period of mask-wearing and avoiding people, putting the kibosh on both the conference and summer school. I cancelled my travel to the UK and stayed on in Dublin **

For the Woolf-Eliot seminar, we had been assigned a final project that could be anything. Since mine was this, and I didn’t exactly have an action-packed schedule in Dublin, I figured I’d go ahead and do it anyway.

I decided to skip Eliot for this project*** and focus on Jacob’s Room, Woolf’s third novel—specifically, on the reviews that it received following its publication in 1922 in the UK and 1923 in the United States.

Jacob’s Room is generally considered Woolf’s first fully experimental novel. It’s the story of Jacob, a young man from an upper-class but down-on-its-luck family who’s intellectual but not, from what I gather, all that smart. He basically thinks everything after Shakespeare is trash. Also, he’s rude to waiters. Everyone is fascinated by him, though, which led me to assume that he’s extremely good-looking. His fan base includes (naturally) his mom, a widow living in the seaside town of Scarborough; Clare, an upper-class woman who seems like appropriate wife material (her thoughts about him are along these lines: “Jacob! Jacob!”), Bonamy, a Cambridge classmate who’s in love with him (he also thinks, “Jacob! Jacob!” a lot), and several women who skirt the line between girlfriend and sex worker.

We mostly see Jacob through the eyes of these people and others. The reviews state that there’s little from Jacob’s point of view, but that’s not quite true: we see his thoughts, for example, on a sailing trip off Cornwall and on a solo tour of Italy and Greece where he experiences a (to this current solo traveler very relatable) mix of elation and existential angst.

Nothing much happens. Jacob finds a sheep’s jaw in Scarborough as a boy. He goes to Cambridge. He moves to London, works at a vaguely described office job, hangs out with his friends and in society, writes intellectual essays that don’t get published, and travels. In the last two pages, we learn obliquely that he has died in the war.

In between all this, there is a lot of description of whatever happens to be going on around Jacob—London traffic, the musings of random people, and the play of light on water. To give you a sense of it, I picked a random passage, which comes after Woolf informs us that little paper flowers in finger bowls are all the rage:

It must not be thought, though, that they ousted the flowers of nature. Roses, lilies, carnations in particular, looked over the rims of vases and surveyed the bright lives and swift dooms of their artificial relations. Mr Stuart Ormond made this very observation; and charming it was thought; and Kitty Kraster married him on the strength of it six months later. But real flowers can never be dispensed with. If they could, human life would be a different affair altogether. For flowers fade; chrysanthemums are the worst; perfect over night; yellow and jaded the next morning—not fit to be seen.

This is a perfect example of what Woolf’s doing here. In the middle of all the flower description, she throws in what could be a whole novel itself about two people who we never hear about again. (And who, by the way, typify one of my pet peeves about people in novels—and, presumably, real life—from 100 years ago: their hasty and uninformed choices of marriage partners.)

But imagine 182 solid pages of this. That high a concentration of brilliance can get exhausting, and it’s possible, as you read, to simultaneously think “Virginia Woolf is a genius” and “if I have to read one more page, I’m going to die.”

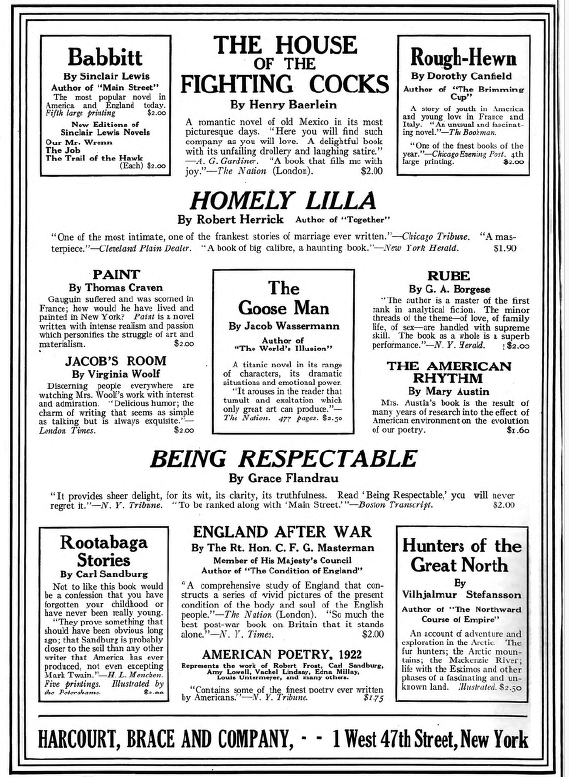

I was curious about what reviewers 100 years ago made of all this. Jacob’s Room was reviewed widely considering its small print run (1,200 copies from the Hogarth Press, which Woolf and her husband owned, followed by a second impression of about 2,000 copies, and, in the United States, 1,500 copies from Harcourt Brace). The 1923 edition of Book Review Digest includes excerpts from reviews of Jacob’s Room in a number of American publications, including The Boston Transcript, The New York World, The New York Times, The Springfield (Massachusetts) Review,**** Booklist, The Dial, Freeman, The Independent, and The International Book Review, a Literary Digest supplement. It also lists UK reviews, mostly from 1922, in The Spectator, The Saturday Review, The Times Literary Supplement, and The New Statesman.

I expected to sit on my born-into-a-world-where-modernism-already-existed perch and scoff at the reviews, which I assumed would be along the lines of the article in the first issue of Time magazine speculating that The Waste Land was a hoax. On the whole, though, they were quite positive, especially the ones in American publications.

In the case of the first review I read, in the modernist journal The Dial, this was not much of a surprise, since the reviewer, David Garnett,***** was a fellow member of the Bloomsbury Group. “Virginia Woolf seems to be the most interesting of the younger writers now living as well as the best of them,” he writes about his friend. He compares Jacob’s Room favorably with James Joyce’s Ulysses, also published in 1922, saying that “it is the things from which mankind instinctively turns away that Mr Joyce delights to write about” while Woolf is “the kind of butterfly that stoops only at the flowers.” He does have one critique: “The book would be better if not quite so many pictures were called up; with all its beauty it is a little bit too much like fire, or like a very amusing person’s memory of life.”

The New York Times included Jacob’s Room in a March 4, 1923, fiction roundup. The anonymous reviewer writes that, though the book is composed of mostly minor events, “it is the manner in which these things are revealed that makes the book of importance, at least as an example of what the younger rebels are doing in England.” The review says of the book’s style that “at first one is uneasily aware of Miss Woolf’s bizarre qualities as a writer of prose, but after one has progressed a way in the book this consciousness rather vanishes.” It wraps up by placing Woolf among a cohort of talented British women writers, none of whom, aside from May Sinclair, I have ever heard of,****** saying, “Her influence is one that modern England needs.”

Some more praise from across the Atlantic:

M.M. Colum in The Freeman: Woolf “shows herself to be possessed of one of the most entertaining minds among contemporary writers—witty, subtle, and ironic.”

H.W. Boynton in The Independent: Woolf’s “air of ironic detachment does not conceal a very warm concern in human affairs. Jacob’s Room, her new study of youth, is full of tenderness, though empty of the facile sentiment often confounded with tenderness.”

Mary Graham Bonner in the Literary Digest International Book Review: “A strangely beautiful book is Jacob’s Room, and the author, Virginia Woolf, has given us many a flash of genius here.”

This was an improvement over the reviews Jacob’s Room had received back home. Rebecca West wrote in the November 22, 1922, issue of the New Statesman that “Mrs. Woolf has once again provided us with a demonstration that she is at once a negligible novelist and a supremely important writer.” Gerald Gould wrote in the November 11, 1922, issue of the Saturday Review that “Mrs. Woolf has written something wholly interesting and partly beautiful. It is at once irritating and encouraging to reflect how much better she would do if her art were less self-conscious.”

Then there’s novelist Arnold Bennett, whose feud with Woolf had the rancor and longevity of a rap beef. First, in the essay “Modern Fiction,” which was published in the Times Literary Supplement on April 10, 1919, Woolf wrote about Bennett, H.G. Wells,******* and John Galsworthy that “it is because they are concerned not with the spirit but with the body that they have disappointed us, and left us with the feeling that the sooner English fiction turns its back upon them, as politely as may be, and marches, if only into the desert, the better for its soul.” Of the three writers, she writes, “Mr. Bennett is perhaps the worst culprit of the three.” She asks about his characters, “How do they live, and what do they live for?”

Then Bennett wrote a book called Our Women: Chapters on the Sex-Discord. The title alone is enough to tell you where this is going, but here’s a passage from the chapter on women writers:

The literature of the world can show at least fifty male poets greater than any woman poet. Indeed, the women poets who have reached even second rank are exceedingly few – perhaps not more than half a dozen. With the possible exception of Emily Bronte no woman novelist has yet produced a novel to equal the great novels of men. (One may be enthusiastic for Jane Austen without putting Pride and Prejudice in the same category with Anna Karenina or The Woodlanders.)********

Woolf, according to the introduction in the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Jacob’s Room, wrote “spirited letters to the New Statesman” in response to this while on a break from writing Jacob’s Room. Then she went a step further and put Bennett in the novel: “For example, there is Mr [John] Masefield, there is Mr Bennett. Stuff them into the flame of Marlow and burn them to cinders. Let not a shred remain. Don’t palter with the second rate. Detest your own age. Build a better one.”

Granted, Jacob, whose consciousness this is streaming through, is being a twit here, but if you’re Arnold Bennet you might not appreciate this fine point, given the whole “burn them to cinders” thing.

Bennett’s next step: An essay in the March 28, 1923, issue of Cassell’s Weekly called “Is the Novel Decaying? The Work of the Young,” in which he says,

I have seldom read a cleverer book than Virginia Woolf’s ‘Jacob’s Room,’ a novel which has made a great stir in a small world. It is packed and bursting with originality, and it is exquisitely written. But the characters do not vitally survive in the mind because the author has been obsessed by details of originality and cleverness.

Woolf’s response to this was the aforementioned “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown.” It was first published in the Nation and Atheneum, a British weekly, on December 1, 1923, then in expanded form under the title “Character and Fiction” in the July 1924 issue of The Criterion in response to a request for an article by (full circle!) editor T.S. Eliot, then as a stand-alone publication by the Hogarth Press.

I’m not going to try to do justice to “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” here. It’s one of the greatest literary essays of all time, a clarion call for modernism. It’s also one of the all-time great literary put-downs. If this is a rap beef, then Bennett is Drake, Woolf is Kendrick Lamar, and “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” is “Not Like Us.” Except that in a hundred years people will remember Drake, and, if people remember Arnold Bennett today, it’s probably because of “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown.”

We could leave things here, with Woolf triumphant.

Except…

Except that Woolf, while a brilliant writer and a defining figure in feminism (with the even more famous essay “A Room of One’s Own” to come in 1929), was also a snob and a horrible racist.

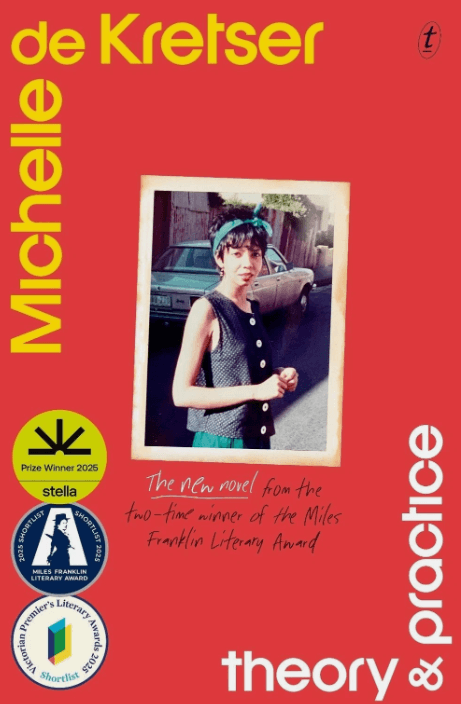

How should we think about this when we’re assessing Woolf’s work? Luckily, I don’t have to answer this question. Instead, I can point you to a wonderful novel about this very issue: Theory & Practice, by the Australian writer Michelle de Kretser. I bought it during a recent trip to Sydney, but it’s available worldwide and was reviewed in the New York Times in February. De Kretser’s heroine is a Sri Lanka-born graduate student in Melbourne in the 1980s, studying Woolf’s diaries as critical theory is taking over English departments at her university and elsewhere. (She’s referred to once late in the novel as Cindy, but I thought of her as “Michelle de Kretser,” which I don’t think is too unfair seeing as that’s a photo of De Kretser as a young woman on the cover of the Australian edition.) Then she comes across Woolf’s racist description of a key figure in Sri Lanka’s struggle against colonialism, but none of the theorists she’s surrounded by think this is important. The novel’s about loving Woolf, and about responding to the flaws of your literary heroes, but it’s also about being young, and going to parties in ramshackle group houses, and the stupid choices you make about love when you’re in your twenties. If that sounds like your thing (and I can’t think of anything that’s more my thing than all this), you should read it.

Jacob’s Room is brilliant, too, and, if I didn’t devour it the way I did Theory & Practice, I’m grateful to have been spurred to read it.

Now I need to get someone to make me read Mrs. Dalloway.

*Obviously, I AM very interested in T.S. Eliot or I wouldn’t do this to myself. But it’s like when I was a full-time Lao language student for ten months at the Foreign Service Institute. FSI is like a high school full of overaged students who are studying just one subject, with schedules along these lines: First period, Lao conversation. Second period, Lao grammar. Third period, Lao reading. Lunch. Fourth period, Lao grammar again. Fifth period, Lao reading again. On Wednesday afternoons they’d spring us for area studies, where we’d study Laos, along with Thailand and Burma. I loved it, but I’d often think, “Can’t we study something else for a change, like Japanese, or the parts of a cell?”

**Having, and recovering from, COVID in Dublin has been way more fun than you’d imagine. I Zoomed in to a seminar on Eliot and translation during the annual meeting, and it was awesome. After a few days of isolation I got the OK from a telehealth doctor to walk outside with a mask. There was a concert series going on that I could hear pretty clearly from my room. One night, the band started singing, “hip hip,” and I thought, oh, they’re covering that Weezer song, and I looked up the program and it ACTUALLY WAS Weezer.

***I haven’t been completely neglecting Eliot. I did my translation seminar paper on a 1992 translation of The Waste Land into Afrikaans.

****The inclusion of The Springfield Republican in the small selection of newspapers The Book Review Digest compiles review from is one of those 100-years-ago mysteries.

*****Garnett is the author of the 1922 novel Lady Into Fox, which I read for my 1920s bestseller book group, and which actually is about a lady who turns into a fox.

******Here they are: Sheila Kaye-Smith, Mary Butts, Ethel Colburne Mayne, F. Tennyson Jesse (which sounds like the name on a fake Facebook friend request and turns out to be a pseudonym), and Elinor Mordaunt.

*******Further ramping up the interpersonal drama, West had a son with H.G. Wells. As I noted in my post on West’s novel The Return of the Soldier, they made some highly debatable child-rearing decisions, including telling him for years that they were his aunt and uncle.

********As fellow blogger Stuck in a Book wrote, “Who on earth would pick The Woodlanders as their ammunition in favour of Thomas Hardy??”