It’s been five months since the end of my year in 1918, but I still haven’t fully readjusted. A few weeks ago I was reading one of the recent novels I had looked forward to during my sojourn. There’s a child in the book who is so brilliant and sweet that I said, “Uh-oh, he’s too good to live.”

He dies!

Take me back to 1918, I said, and put the book down.

Since it’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,* I decided to read a book by an Asian-American writer of that era. Or, rather, the Asian-American** writer of that era, Winnifred Eaton, author of, among many other books, Marion: The Story of an Artist’s Model.

Winnifred Eaton was the younger sister of Edith Maude Eaton, who wrote about the Chinese community in Seattle and San Francisco under the pseudonym Sui Sin Far. I read Mrs. Spring Fragrance, a collection of Sui Sin Far’s stories, last year, but she died before 1918 so I didn’t write about her beyond a brief write-up on the Book List.*** It was when I was looking into Edith’s life (okay, reading her Wikipedia entry) that I learned about Winnifred.

Edith and Winnifred were two of the fourteen children of a British merchant named Edward Eaton and his wife Grace, who had been a Chinese slave, performing in the circus as the target in a knife-throwing act, before being rescued and adopted by British missionaries. (UPDATE 6/9/2019: I thought the knife-throwing story seemed kind of bogus, but it was in Edith’s Wikipedia entry with a footnote so I decided to include it–we’re not exactly the New Yorker here when it comes to fact-checking. I’ve since looked this up in biographies of Edith and Winnifred. Both say that their mother’s origins are hazy and there is no evidence of the circus story beyond family legend.) Edith was born in England in 1865, shortly before the family moved to Canada. They moved back to England and then back to Canada, where Winnifred was born in 1875. Their father struggled to support his large family, working first as a clerk, then as an artist, then turning to smuggling Chinese people into the United States from Canada.**** Both Edith and Winnifred began writing for magazines as teenagers.

Marion: The Story of an Artist’s Model was published in 1916. By this time, Eaton had written a number of best-selling romance novels under the fake Japanese name Onoto Watanna.***** She and her sister Sarah, whose married name was Bosse, had also published The Chinese-Japanese Cook Book, which reassured readers that “when it is known how simple and clean are the ingredients used to make up these oriental dishes, the Westerner will cease to feel that natural repugnance which assails one when about to taste a strange dish of a new and strange land.”

Marion wasn’t published under the pseudo-Japanese pseudonym; Eaton was identified on the title page only as “Herself and the author of ‘Me.’” Me: A Book of Remembrance was a semi-autobiographical novel published in 1915. It’s the story of Nora Ascough, who, like Winnifred, moves from Canada to Jamaica and then to the United States. (UPDATE 4/7/2021: The New York Times outed Eaton as the author of Me in an article published on October 10, 1915, basing its argument primarily on clues in the text that the author was half-Japanese, as Eaton supposedly was.)

Not having read Me, I assumed as I read Marion that it was autobiographical. It turns out, however, to be the story of Winnifred’s older sister (and cookbook co-author) Sarah. The Eaton family is clearly identifiable: there’s the struggling artist father (she leaves out the smuggling part); the foreign mother; killjoy older brother Charles (Edward Charles in real life), who complains about Marion looking at the naked Jesuses in the Catholic store; responsible older sister Ada (Edith), who’s always pestering Marion to send money home; and Nora again. The siblings’ Chinese heritage is never explicitly mentioned, but we do learn that they’re foreign-looking and that a neighbor calls them “heathenish.”

Marion is the flibbertigibbet of the family, and those around her predict that she’ll come to a bad end, but she’s a talented actress and artist. Also, as people constantly tell her, beautiful. She’s about to launch an acting career when she meets and falls in love with the Hon. Reginald Bertie (pronounced Bartie). He’s just her type, blond and handsome. Reggie convinces Marion to give up acting, they get engaged, and he strings her along for several years, afraid to tell his family about her. It’s because I’m poor, Marion tells herself, although her foreign origins probably aren’t helping.

When Reggie asks her to “be my wife in all but the silly ceremony,” Marion flees to Boston, where she gets work as an artist’s assistant and model. The best money is in nude modeling, which Marion resorts to once, when she’s practically starving. It doesn’t go well. “The model is crying,” a student in the class she’s posing for observes. She yells at the class, calling them devils and beasts, and leaves.

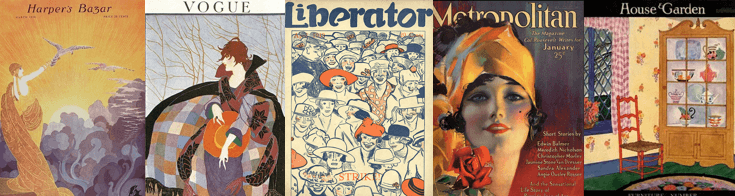

When Reggie writes and says he’s coming for her (still no mention of a wedding), she takes off for New York. After turning down a job as a chorus girl, she settles in Greenwich Village and falls in with a group of artists, including one named Paul, who, if the book’s illustrations are to be trusted, looks exactly like Reggie. (That’s him at the upper left below.) Unlike the hacks who surround him, he has high artistic principles (which he expresses in vapid terms—art theory isn’t Eaton’s strength******). I won’t reveal the ending because I want you to read this book, but no prizes for guessing what happens.

Winnifred Eaton is no Jean Rhys or Edna Ferber as a stylist, but I loved reading about the large, bohemian Montreal family, the Boston art scene, and the struggling New York artists with their dingy boarding houses, cheap table d’hôte dinners, and unsanitary habits. (“Some of the artists in the building were pretty dirty,” Marion tells us, italics hers). There are wonderful period details, like when Marion is part of a “living pictures” show (symbolizing things like Youth and Rock of Ages) that takes Providence by storm. She gives us a wonderful sense of how a beautiful and educated but poor woman gets by in life, the compromises she makes, and the ones she refuses to make.

Eaton was evasive about her Chinese heritage even when writing under a pseudonym. She took her pretense of being Japanese beyond the made-up name, claiming to have born in Nagasaki, the descendant of noblemen. But she’s a vivid and honest chronicler of a fascinating milieu.

I can’t wait to read Me.

*But we are not, you will notice, “celebrating” APAHM. If you look to the right, you’ll see that I’ve fallen into a naming rut—my recent posts are a veritable fiesta. If you’re reading this in the future (which I realized as I proofread this that you definitely will be, since this post will push the last celebration off the list), here’s what I’m talking about:

**Well, Asian-Canadian-American.

***I highly recommend this collection, especially the first two stories.

****There’s a story on this topic in Mrs. Spring Fragrance.

*****That is, it’s not only not her real name, it’s also not a real Japanese name.

******Eaton does do a good job, though, of depicting social gradations among artists—the ones who paint on plates and cloth, the ones who knock off old masters, the society artists, and the art for art’s sake ones like Paul. Then there are the different levels of models—the ones like Marion who won’t take their clothes off so don’t make much money; the nude models at the art schools who drop their drapes when the teacher shouts, “Pose,” and at the lowest end, Marion’s friend Lil, who prances around in her birthday suit in the studio where Marion works.

This was a terrific read! I will definitely add these to my reading list.

LikeLiked by 1 person