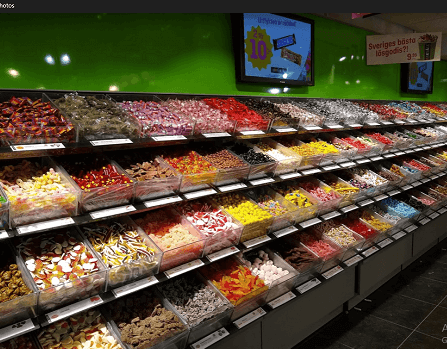

Hello from Sweden, the land of ubiquitous candy

and adorable groceries

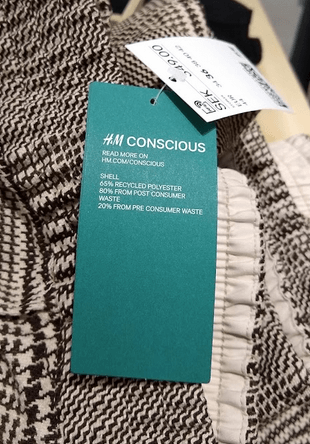

and clothes made of garbage

and quaint swear words (“Devil!”)!

I’m spending September in Uppsala, half an hour outside Stockholm. The town is home to a 500-year-old university, so history is ever-present.

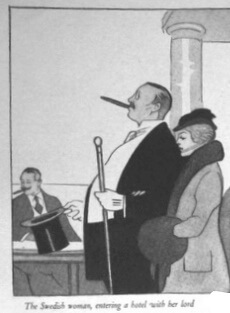

To get a sense of what was happening in Sweden a century ago, a relative blip in this ancient town, I turned to my trusty Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature, 1915-1918. It pointed me in the direction of an article in the February 1918 issue of the women’s magazine The Delineator called “Women All Too Womanly – In Sweden.” The problem with Swedish women, it turns out, is that they’re not sparkling enough in society. They walk behind their husbands all self-effacing like this

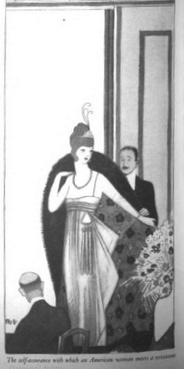

instead of making a grand entrance like this

and enchanting their dinner companions with bon mots.*

Not being convinced that skin exposure = emancipation, I decided to look elsewhere for insights into ca. 1919 Swedish women.** An article in the April 1915 issue of the children’s magazine St. Nicholas called “Selma Lagerlöf, Swedish Genius” seemed like just the ticket.

Lagerlöf, I learned, was born in 1858 and grew up on an estate called Mårbacka in west central Sweden. A semi-invalid as a child, she sat at home listening to visitors’ stories while her siblings played outdoors. She heard about wolves chasing sea captains across the snow and the Devil*** paying social visits, rocking in a rocking chair while the lady of the house played the piano.

The family experienced financial setbacks that eventually forced them to sell Mårbacka, and Lagerlöf set off for Stockholm to study teaching. While she was there, she started writing down those childhood tales. In 1891 she published her first novel, Gösta Berling’s Saga. It’s the fantastical story of a Lutheran minister who is sacked for drinking and carousing, takes up with a group of eccentric vagrants, and eventually comes to see the error of his ways.**** “And in less time that it takes to get around it,” St. Nicholas tells us, “the world hailed the writer as a genius.” Other novels, and other accolades, followed.

Like, for example, the Nobel Prize in Literature, which Lagerlöf won in 1909, beating out other contenders such as Leo Tolstoy and Mark Twain, both of whom died the next year. She was the first woman to be awarded the prize.

If you’re thinking something sounds off here, there are a few things you need to know about the early days of the literature Nobel, which was first awarded in 1901. One is that writers from the Nordic countries had a distinct home field advantage, winning seven of the first 18 awards.*****

Also, the award in its early days bore the stamp of the Swedish Academy’s conservative permanent secretary, poet Carl David af Wirsén, who thought Nobelists should display “a lofty and sound idealism.” This, in his mind, disqualified not only Tolstoy and Twain but writers closer to home such as playwrights Henrick Ibsen of Norway and August Strindberg of Sweden.******

And also, for a while, Selma Lagerlöf, whose characters, redeemed in the end or not, weren’t wholesome enough for af Wirsén’s liking. Whenever her name came up as a possible Nobelist, he would put forward other candidates, sometimes equally “unwholesome” writers who at least weren’t Swedish. But his fellow Swedish Academy members finally had their way in 1909, leaving af Wirsén a broken man.******* He died in 1912.

With her Nobel Prize money ($40,000, St. Nicholas informs us), Lagerlöf bought back Mårbacka, where she lived for the rest of her life.

St. Nicholas tells us that

With all her fame and fortune, Selma Lagerlöf remains the pleasant, unpretentious, fun-loving, kind-hearted woman of her school-teacher days. She has never married, and, since she is now about fifty-six years old, she will probably remain a spinster. But her friends are thick as the leaves in her beloved forest in full summer.

A spinster! Fun-loving! Friends thick as leaves in the forest! What could this mean? Having been through this before, I had my suspicions. I Googled “Selma Lagerlöf lesbian,” and the true story of her life emerged.

A few years after the publication of Gösta Berling’s Saga, Lagerlöf met fellow writer Sophie Elkan, who became her lifetime friend and companion. The daughter of German Jewish immigrants, Elkan had lost her husband and only daughter to tuberculosis in 1879, and she dressed in mourning for the rest of her life.

Lagerlöf, apparently, was smitten from the beginning. At their first meeting, she lifted up Elkan’s widow’s veil, unbidden, and said, “You are very beautiful. I know we will become friends.” In a letter to Elkan, she wrote,

These kisses of yours that you convey in your letters, they are a great puzzlement to me. How am I to understand such merchandise? Are they promissory notes, or ‘samples without value’? Are such debts to be repaid in rooms milling with people, or in the greenhouse at Nääs?…In Copenhagen I see so many relationships between women that I must try to comprehend in my own mind what Nature’s intention is with this.********

Lagerlöf’s desire for physical intimacy seems to have been unrequited, though. In a letter written before a planned meeting, Elkan wrote, “Hands off!”

Still, the two remained devoted friends, traveling together to Italy and to Egypt and Palestine, the setting for Lagerlöf’s successful novel Jerusalem, which was published in parts in 1901 and 1902, with this dedication:

In 1902, Lagerlöf met Valborg Olander, an educator and suffragist, and the two began a passionate affair. Life became complicated. Elkan may not have wanted a physical relationship with Lagerlöf, but that doesn’t mean she wanted someone else filling this void.

Jealousy and subterfuge ensued. Olander’s letters brimmed with passion, and Lagerlöf apparently destroyed many of them so that Elkan wouldn’t find them. Her own letters to Olander were equally ardent. “Every time you are here, I try to kiss you so I can be happy for a few days, but I long for you even before you are out of the gate,” she wrote in July 1902. In another letter, she expressed the wish that Olander would stay overnight—“that would be divine.”

Elkan grew desperate, writing, “Oh dear, you won’t take Valborg—is it Valborg?—instead of me, will you?”

Olander became deeply involved in Lagerlöf’s literary affairs as well, and Lagerlöf wrote to her saying that “you are becoming a real writer’s wife.” Eventually the trio reached an uneasy peace, which lasted until Elkan’s death of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1921.

Lagerlöf remained devoted to Elkan after her death. Toward the end of her life, she started writing down the stories that Elkan had told her about growing up as a Jewish girl in Sweden, thinking of tales of Vikings and kings as her own heritage until a schoolmate mimed a long nose and said, “Jew kid!” Lagerlöf never finished the project, but the stories she completed were published after her death, in 1940, at the age of 80.

I’ve found Lagerlöf’s books on sale at every bookstore I’ve visited in Sweden,

but beyond her native country she’s a literary footnote, a hometown favorite who won the Nobel in the years before the award broadened its geographic and literary horizons. If she were alive today, she wouldn’t be a contender. On the other hand, if she were alive today, she would be able to live her life openly, and with pride.

*The illustrations are by future New Yorker cartoonist Rea Irvin.

**In fairness, the writer of the article, American suffragist Frances Maule Björkman, does end up with a more nuanced view of Swedish women, who turn out to have not the slightest interest in sparkling in society but interesting things to say under other circumstances.

***Oops, sorry, I mean the Evil One.

****It was Greta Garbo’s performance in the 1924 film adaptation of this novel that brought her to the attention of Louis B. Mayer and launched her American career. You can watch some scenes from the film, with commentary, in this interesting five-minute clip.

*****This was partly because, during most of World War I, the prize was awarded only to writers from non-combatant countries. To this day, only France, the United Kingdom, and the United States have more literature Nobelists than Sweden, which is tied with Germany at eight.

******The Nobel Prize website fesses up to the errors of its ways: “As to the early prizes, the censure of bad choices and blatant omissions is often justified.”

*******Or, as a vivid if probably not very accurate Google Translate translation from this essay in Upsala Nya Tydning puts it, “a lonely and isolated loser.”

********This translation is from a fascinating article called “Selma and her Lovers” in the June 2007 issue of Scanorama, the SAS inflight magazine (!). Other translations are mine, with the help of Google Translate.

Very interesting

LikeLiked by 1 person