Early this year, I was reading H.L. Mencken’s fiction roundup in the January 1920 issue of The Smart Set in search of a good book. I didn’t have much hope, given Mencken’s generally dim view of the novels of the day.

So I was pleasantly surprised to come across his review of Henry B. Fuller’s novel Bertram Cope’s Year, which he calls “a very fair piece of writing, as novels go. A bit pizzicato; even a bit distinguished.” I enjoy academic novels, and Mencken described Bertrand Cope’s Year as a comic romp featuring a young college instructor who haplessly endures various townspeople’s attempts to ensnare him into romantic and social entanglements. I Googled the book, expecting to get the usual array of low-quality Amazon reprints and not much else.* To my surprise, I found a Wikipedia entry saying that Bertrand Cope’s Year is “perhaps the first American homosexual novel.”

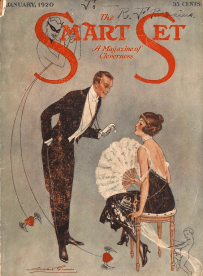

I immediately downloaded it on my Kindle and started reading. I made it about halfway through, but, this being early March, life and COVID intervened and I ended up putting it aside.** When I resumed, it was in the much more palatable form of this attractive annotated edition by Broadview Editions:

Bertram Cope is a 24-year-old instructor and master’s degree student at a Northwestern-like university in the Evanston-like town of Churchton, Illinois. Cope is strikingly handsome; I picture him as a young blond Cary Grant. As soon as he shows up, the entire population of Churchton, male and female, goes into a swoon and sets out to ensnare him. Medora, a prosperous widow, installs him in her social set and, although clearly pining for him herself, throws her three young artistic protégées in his path. Much sitting in parlors ensues.

Randolph, a middle-aged businessman, schemes to become Bertram’s “mentor,” but, you know, the kind of mentor who moves to a bigger apartment so as to have a more suitable setup in case Bertram comes over for dinner and gets snowed in for the night. (This fails, but he does finagle some skinny-dipping at the Indiana Dunes.)

Meanwhile, all Bertram wants to do is set up housekeeping with his devoted friend Arthur, who’s back home in Wisconsin. When Randolph invites Bertram to accompany him on an overnight trip, Arthur puts the kibosh on it, even though the “fickle” Arthur (Bertram’s word) has been known to go on similar weekend jaunts himself.

(We’re getting into spoiler territory here, so if you’re planning to read the book, or just find plot summaries tedious, skip down to the photo of Henry Fuller.)

Amy, the most determined protégée, takes to stalking Bertram. One day they just happen to meet on the university campus and end up going for a sail. The boat capsizes, the two struggle to the shore, and Amy turns this into a tale of heroism on Bertram’s part even though, in Bertram’s opinion, if anyone did any saving it was Amy. This is the most exciting thing that has happened in Churchton in months, even more exciting than the time when Bertram fainted during one of Medora’s soirées. Amy starts blathering about “happiness” on their walks, and, without Bertram knowing exactly what happened, they end up engaged.

Arthur, as you can imagine, is NOT happy. Neither are Medora and Randolph, who conspire to throw a hail-fellow-well-met type named Pearson into Amy’s path. Between that and Bertram’s unavailability to see Amy ever, which even she sees as a red flag, the engagement comes to an end, to Bertram’s huge relief.

Bertram and Arthur set up a home together and live in blissful cohabitation, so blissful that it starts raising eyebrows. Their PDAs prompt Medora’s disabled relative Foster, whose main activity in life is making caustic comments, to recall the time when similar behavior by a newlywed couple in Sarasota prompted an elderly woman to complain that they “brought the manners of the bedchamber into the drawing-room.”

Further complications ensue in the form of Hortense, another of Medora’s protégées, who makes a play for Bertram by painting his portrait. When Bertram, having learned his lesson from the Amy fiasco, rejects her, she flies into a fury, tears the portrait in half, and tells Bertram that his “preposterous friendship” with Arthur will not last long.

Arthur, meanwhile, has thrown himself into his female part in the campus theatricals.

Their room came to be strown with all the disconcerting items of a theatrical wardrobe. Cope soon reached the point where he was not quite sure that he liked it all, and he began to develop a distaste for Lemoyne’s preoccupation with it. He came home one afternoon to find on the corner of his desk a long pair of silk stockings and a too dainty pair of ladies’ shoes. “Oh, Art!” he protested.

When the big night finally arrives, the townspeople squirm at Arthur’s all-too-convincing female impersonation at first, but his final number brings down the house. Unfortunately, Arthur doesn’t know when to stop, and his post-curtain pass at a male costar who can’t take a joke (if it was one) is met with a whack. No prizes for guessing who gets drummed out of town as a result of this incident.

Bertram, having earned his master’s degree, hightails it for the East Coast, where he has gotten a job at an “important university.” Medora and Randolph admit defeat, but Carolyn, the third protégée, is in hot pursuit. The story ends with us wondering whether Bertram ends up with her or with Arthur.

“AR-THUR, AR-THUR, AR-THUR, AR-THUR,” contemporary readers call out in unison. Given that Bertram managed to escape Amy’s clutches when she was a) right there in Churchton and b) actually engaged to him, I’m fairly confident that he’ll succeed in giving Carolyn the slip. But this wasn’t such a slam-dunk case in 1919. Once again, I picture Cary Grant’s desperate, trapped expression at the supposedly happy ending of every romantic comedy he starred in.***

Who, I wondered, was Henry Fuller? And how did this book come to be published in 1919?

Fuller, it turns out, was a well-established 62-year-old Chicago writer when Bertram Cope’s Year was published. He got his start in his twenties with allegorical travel novels about Italy, which sound heinous but brought him attention among the genteel New England literary set. He then turned to realist novels about his gritty native city. Along the way, he wrote a play about a young man who commits suicide at the wedding of his former (male) lover.

Fuller also wrote literary criticism for The Dial and other publications. Once I looked up his reviews, I realized that I had read quite a few of them.**** If you want to save yourself the trouble of spending a year reading as if you were living 100 years ago, just take my word for it that all literary criticism, by Fuller and everyone else (except H.L. Mencken), sounds exactly like this snippet from Fuller’s review in The Dial of a book of lectures by Lafcadio Hearne:

The depiction of homosexuality in Bertram Cope’s Year is often described as subtle, an argument I have trouble buying unless your definition of subtle is that no one marches down the street waving a rainbow flag. Judging from all the rejections Fuller received, the publishing industry had no trouble understanding what the book was about. It ended up being published, at Fuller’s expense, by a small Chicago publishing house owned by his friend Ralph Fletcher Seymour.

The conventional wisdom, to the extent that there is conventional wisdom about Bertram Cope’s Year, is that the book was ignored or condemned by critics. However, in addition to Mencken’s write-up, it received favorable or semi-favorable reviews from The Bookman (“the kind of novel which must be enjoyed not for its matter so much as for its quality, its richness of texture and subtlety of atmosphere”), The Booklist (“live enough people and a sense of humor hovering near the surface”), and The Weekly Review (“a mild affair altogether whose sole and sufficient distinction lies in the delicate perfection of its setting forth”). This is a fair amount of press for a book from a small publisher. None of the reviews mention the homosexuality angle. Poor Arthur is nowhere to be seen, and some of the reviews portray Bertram’s desperate flight from Carolyn as a possible budding romance. It wasn’t until Carl Van Vechten published a laudatory essay in 1926 that the true subject of the book was acknowledged.

What was going on here? Did the reviewers just not get it? This seems impossible, but it’s hard, looking back from the knowing present, to see things through the lens of another era.***** Maybe they were just protecting the delicate sensibilities of their readers? But, in that case, why bother to review the book at all?

It was a moot point in the end. Bertram Cope’s s Year sold very few copies. “My disrelish for the writing-and-publishing game is now absolute,” Fuller wrote to his friend Hamlin Garland in May 1920. ”There seems to be no way for one to get read or paid, so—Shutters up.” Fuller continued writing non-fiction, but he abandoned fiction for almost a decade, before writing one last novel that was published posthumously in 1929.

Fuller fell into obscurity after his death, but Bertram Cope’s Year has found a new life in the 21st century. The book was republished in 1998, with an afterword by Andrew Solomon, and a critical edition (the one I read) was published in 2010.

Wikipedia’s assertion that Bertram Cope’s Year is the first gay American novel falls apart upon examination. There is, for example, Bayard Taylor’s Joseph and His Friend, published in 1870, about a young Pennsylvania farmer who falls in love with a man who cares for him after a train crash. Edward Prime-Stevenson’s 1906 novel Imre: A Memorandum, is arguably the first American novel to depict an actual gay relationship, although some claim that it doesn’t count because it was published in Europe, where New Jersey-born Prime-Stevenson lived. Alan Dale, the hack drama critic whose play about an unrepentant unwed mother I wrote about a while back, published the gay melodrama A Marriage Below Zero in 1889, two years after he left Britain for the United States.

So I guess the best claim we can make for Bertram Cope’s Year is that it’s the first novel by an American writer that was published in the United States, features a loving gay couple, and doesn’t end in a tragic death.******* Which is a bit of a mouthful as firsts go, but still one worth celebrating.

*Don’t get me started on the shady business of print-on-demand. Four-point font! Typos on the cover! The totally wrong book (I’m talking to you, Robert Chambers’ The Tree of Heaven labeled as May Sinclair’s The Tree of Heaven)!

**Which is what I do with almost every book I start reading on my Kindle in any case.

***I didn’t actually re-watch every Cary Grant romantic comedy to fact-check this assertion, so I’m open to correction here. Still, I do get a “gay man trapped by determined women” vibe from his oeuvre as a whole.

****Among other things, Fuller started a heated debate about whether novels were too long or too short that I came in in the middle of. (No one thought that they were the right length, apparently.)

*****It wasn’t until probably my fourth reading of The Great Gatsby a decade or so ago that it struck me that the scene at the end of the second chapter where Nick is in Myrtle’s neighbor’s apartment is the aftermath of a gay sexual encounter. It seemed so unmistakable that I marveled that I could ever have missed it. I’ll try to remember to put in a link when the copyright expires at the beginning of 2021. If I forget, remind me. (UPDATE 6/4/2021: Here it is.) (P.S. If you didn’t look at the caption below the photo of the person wearing the hat, go back and check it out!)

******This photo was posted on the Flickr site of a collector of vintage postcards who thinks it looks a lot like Bertram and Arthur. I agree!

*******Although I worried a little, given that Bertram, in addition to his fainting episode, was constantly getting sick.

I read this thanks to your posting about it, a very strange book but I’m glad I read it. It’s so modern in its prose style and I loved that it wasn’t about 1. discovering he’s gay 2. struggling to accept he’s gay 3. burying your gays, which is a bar very few pieces of media clear even now. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad that my post led you to this book! I agree with all your comments. I love the way that Bertram is gay in the same way that heterosexuals in books are heterosexual–it’s the context in which his problems play out, rather than the problem itself.

LikeLike