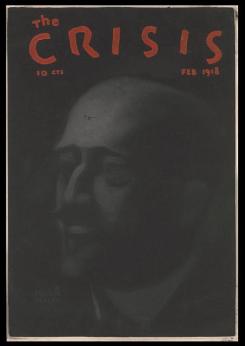

The February 1918 issue of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, headlined EDITOR’S JUBILEE NUMBER, starts with this note: “The Editor of the CRISIS will celebrate his fiftieth birthday on the twenty-third of February, 1918. He would be glad on this occasion to have a word from each of his friends.” The editor was W.E.B. Du Bois, born 150 years ago today.

The Crisis, February 1918

The issue includes an autobiographical essay by Du Bois called “The Shadow of Years.” He tells of his ancestry:

a flood of Negro blood, a strain of French, a bit of Dutch, and thank God! No “Anglo-Saxon”

—his childhood in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, playing comfortably with his white friends and largely unaware of the country’s vast racial divide:

I think I probably surprised my hosts more than they me, for I was easily at home and perfectly happy and they looked to me just like ordinary people, while my brown face and frizzled hair must have seemed strange to them

The Crisis, February 1918

—encountering other African-Americans in large numbers for the first time at Fisk College in Tennessee:

Lo! My people came dancing about me—riotous in color, gay in laughter, full of sympathy, need, and pleading; unbelievably beautiful girls—“colored” girls—sat beside me and actually talked to me while I gazed in tongue-tied silence

—and the “Days of Disillusionment” that fueled his desire to work for the upliftment of his people:

I began to realize how much of what I had called Will and Ability was sheer luck. Suppose my good mother had preferred a steady income from my child labor, rather than bank on the precarious dividend of my higher training?…Suppose Principal Hosmer had been born with no faith in “darkeys,” and instead of giving me Greek and Latin had taught me carpentry and the making of tin pans?

Second edition, 1903

If you want to learn more about the human side of this towering (and sometimes intimidating) thinker, you can find the “The Shadow of Years” here. Or you can read “Of the Meaning of Progress,” the essay in Du Bois’ 1903 classic The Souls of Black Folk about his days as a young teacher in a rural Tennessee community. (I’ve been listening to the audiobook, wonderfully narrated by Rodney Gardiner.)

In “The Shadow of Years,” Du Bois presents himself as an old man. “The most disquieting sign of my mounting years is a certain garrulity about myself, quite foreign to my young days,” he begins. He ends the essay as follows:

Last year, I looked death in the face and found its lineaments not unkind. But it was not my time. Yet, in nature sometime soon and in the fullness of days, I shall die; quietly, I trust, with my face turned South and Eastward; and dreaming or dreamless, I shall, I am sure, enjoy death as I have enjoyed life.

But Du Bois lived almost long enough to celebrate another Jubilee, dying in Ghana in 1963 at the age of ninety-five.

As for his request in The Crisis for a word from each of his friends, I’ll just say this, from the distance of a hundred years:

Thank you.