If you’ve followed My Year in 1918 since the beginning, you may be thinking around now, “What’s with this person? She said she was going to read her way through 1918, but all she does is sit around looking at magazines. She’s mentioned one book so far, and it wasn’t exactly Dostoevsky.”

As my Book List will attest, I have, in fact, read other books. I just haven’t had much to say about them. But now I’ve read a book that I have a lot to say about—Jean Webster’s 1912 epistolary novel Daddy-Long-Legs.

First edition, 1912

Daddy-Long-Legs—which I’d read before, when I was twelve or so—is the story of Jerusha Abbott, a foundling who was raised, if that’s the word for it, in the grim John Grier Home. A trustee of the home offers to put her through college. She’s supposed to write him a letter every month, and he keeps his identity secret. She renames herself Judy and—despite never having seen the inside of a house—adapts quickly to college life. She sends her benefactor cheery, breezy missives, illustrated with whimsical drawings. She saw his elongated shadow in the hallway once, so she nicknames him “Daddy-Long-Legs.”

Daddy-Long-Legs, illustration by Jean Webster

Judy tells Daddy-Long-Legs everything—about her (quickly overcome) academic struggles, her fun-loving roommate Sally McBride of Worcester, Mass.*, her snooty roommate Julia Pendleton, and her growing fondness for Julia’s young uncle, Jervie, who’s a socialist and not at all like the rest of his clan.

If you haven’t read Daddy-Long-Legs, and are planning to, and are the world’s densest reader**, then stop here, because I’m going to give away the ending.

JERVIE AND DADDY-LONG-LEGS ARE ONE AND THE SAME!

Judy discovers this after she writes to Daddy-Long-Legs, broken-hearted after turning down Jervie’s marriage proposal because of the vast social divide between them, and begs for a meeting. Her last letter, written after she discovers the truth and accepts his proposal, is an outpouring of joy.

From a twenty-first-century perspective: No. Just…no.

Run, Judy, run! (Daddy-Long-Legs, illustration by Jean Webster)

How about this instead?

Dear Whoever,

Of all the sick mind games anyone ever played, yours is the sickest. I came from nowhere. I had nobody. Nobody, that is, except the benefactor who lifted me from poverty—in spite of everything, thank you for that—and the man I loved. I told my benefactor all about him—his generosity, his liveliness, but also his little inconsiderate acts (showing up at inconvenient times and expecting everyone to drop everything) and his horrible family. And you let me do this—for FOUR YEARS—even as our friendship turned to love.

Two men in the world cared about me. Now it’s just one. Daddy-Long-Legs is dead. No, worse—he never existed. I can always find another lover, but I’ll never have another father. I’ll miss him, Jervie, more than I’ll miss you.

And all that string-pulling along the way…making me spend the summer at your old nanny’s farm when I begged to go to the McBride family camp in the Adirondacks. “It’s the kind of nice, jolly, care-free time that I’ve never had; and I think every girl deserves it once in her life,” I said. But no, to the farm it was—so that I could keep you entertained during your brief visit. I’m not your plaything, Jervie.

You probably think I’m going to run off and marry Jimmie McBride. But you know what? I’m twenty-one. I’ve never lived anywhere but in a foundling asylum and a girls’ college. I’m not going to marry anyone. I need some time on my own.

Not yours, not anyone’s,

Judy

There. That’s better.

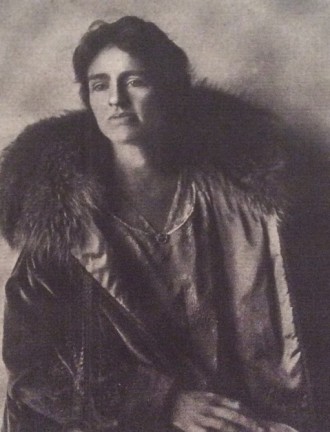

Jean Webster, Bookman magazine, July 1916

The ending aside, though, Daddy-Long-Legs was my most enjoyable read of the year so far—bright and breezy and fun. Jean Webster seems like she would have been bright and breezy and fun too. But her life was shadowed with tragedy. Her father started a publishing business with Samuel Clemens (AKA Mark Twain), who was his wife’s uncle, but it ended up going broke, and he committed suicide when Jean was fourteen. She had a long affair with Standard Oil heir Glenn Ford McKinney, whose wife suffered from severe mental illness. They finally married in 1915, after his divorce, but she died in childbirth the next year, at the age of thirty-nine. Her daughter was named Jean in her memory.

First edition, 1915

A bright light, gone far too soon. But she left a lot of books behind. There’s a sequel to Daddy-Long-Legs called Dear Enemy, which I’ll read later in the year.*** For now, on to more serious fare—Willa Cather’s O Pioneers!

I’m sure it will be great, but I miss Judy already.

*Shout out!

**Well, tied with twelve-year-old me