Good news, chocolate lovers! Good Housekeeping magazine has given chocolate a big thumbs-up. Writing in the January 1918 issue, Dr. Harvey Wiley says that it

contains considerable food-value. A small bulk furnishes a large amount of nutrition. It has in its composition more protein than has wheat flour, and about twenty times as much fatty material, and a considerable proportion of starch as well. It is, therefore, extremely nourishing and is usually easily digested.

Dr. Wiley provides a number of recipes, including hot cocoa (a harmless way to disguise milk if your child won’t drink it), chocolate pudding, and an unappetizing-sounding chocolate corn-starch mold. He compares chocolate recipes, like cake, with their non-chocolate equivalents, and shows how, in each case, the chocolate version provides more nourishment.

Nourishment being measured in, um, calories.

Most of Dr. Wiley’s advice is more sensible than this. In the March edition of his monthly Good Housekeeping feature “Dr. Wiley’s Question-Box,” C. A. B. of New York asks:

A friend of mine is most anxious to join a certain branch of the U.S. service, but due to his height (6 ft. 2 in.) finds it will be necessary to take on 25 pounds additional weight before he can qualify. Can you give him advice as to how he can go about getting up to the required number of pounds?

Dr. Wiley replies:

If your tall friend has a normal digestion he can increase his weight by over-eating and under-exercising. If he will go into a state of hibernation, so to speak, sleep fourteen hours a day, and lie perfectly still the rest of the time, eat large quantities of starch, sugar, ice-cream, cake, and other fattening substances, he will probably be able to gain twenty-five pounds in weight. When he does this, however, he will be far less efficient physically than he was before, and less suited to serve his country.

Dr. Wiley tells M. MacE. of Ohio that, whatever the Food Administration might say, corn syrup is not in fact “the most healthful and easily assimilated of all sweets.” He tells A.L.S. of Kansas, a flour miller, that white flour is “the base of nearly all the bad nutrition in the United States.”

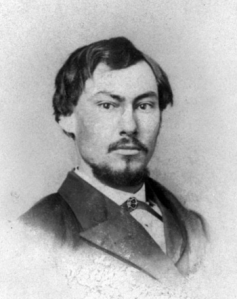

I was curious to find out more about Dr. Wiley. He turned out to be a fascinating character and an important figure in U.S. history.

Dr. Wiley was born in a log cabin in Indiana in 1844. He attended medical school after serving in the Civil War and then taught at Butler College and Purdue University. He was highly regarded as a teacher, but his unusual behavior raised eyebrows. According to his autobiography, a member of Purdue’s board of trustees stated that:

we are deeply grieved at his conduct. He has put on a uniform and played baseball with the boys, much to the discredit of the dignity of a professor. But the most grave offense of all has lately come to our attention. Professor Wiley has bought a bicycle. Imagine my feelings and those of other members of the board on seeing one of our professors dressed up like a monkey and astride a cartwheel riding along our streets.

After being passed over for Purdue’s presidency, apparently for being “too young and too jovial,” he was appointed chief chemist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and moved to Washington, D.C., where he was the second person to own an automobile (and the first to have a serious accident).

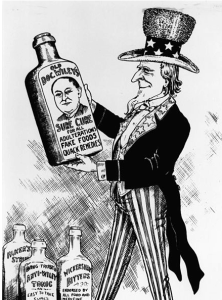

Dr. Wiley skyrocketed to national fame after assembling a group of healthy young civil servants and testing various food additives on them, steadily increasing the amounts until they became ill. The group became known as the “Poison Squad.” (You can read about it in this 2013 article in Esquire.) He was given a more dignified nickname—“Father of the Pure Food and Drugs Act”—after passage of the landmark law in 1906, and was appointed the first commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration. His enforcement of the act won him powerful enemies, though, and he resigned in frustration in 1911. According to the FDA, a newspaper headline read, “WOMEN WEEP AS WATCHDOG OF THE KITCHEN QUITS AFTER 29 YEARS.”

Dr. Wiley spent the rest of his career at Good Housekeeping. There was some irony in this, since, according to Esquire, he was an outspoken misogynist, given to calling women “savages” and questioning their brain capacity.

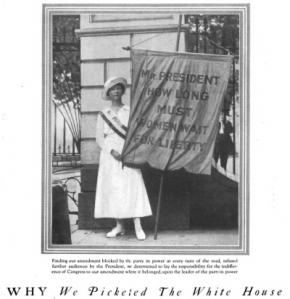

He came around in the end, though. In 1911, the longtime bachelor married Anna Kelton, a prominent suffragist who was half his age. They had two sons. Anna Kelton Wiley contributed an article to the February 1918 issue of Good Housekeeping called “Why We Picketed the White House.” The magazine ran a disclaimer next to the article saying that, while it does not believe in picketing the White House,

when the White House pickets secured so distinguished a recruit as the wife of Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, we offered to open our pages to a statement of the reasons for the picketing.

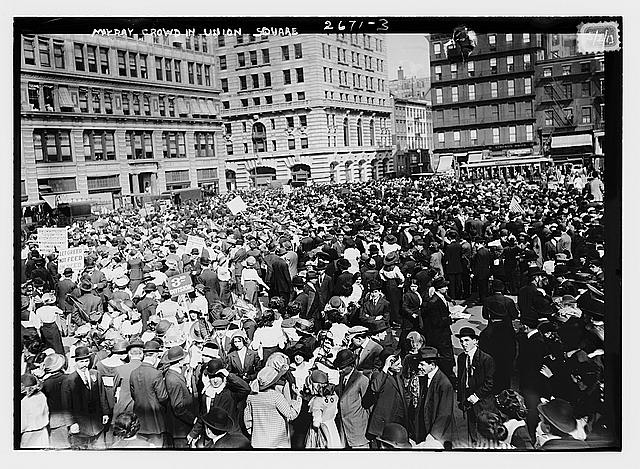

Anna Kelton Wiley writes in the article that it was only after attempts to gain the vote through less confrontational methods failed that she and other suffragists*

determined to organize at the White House gates, a silent, daily reminder of the insistence of our claims…We determined not to be put aside like children…Not to have been willing to endure the gloom of prison would have made moral slackers of all. We should have stood self-convicted cowards.

In this effort, she writes, she was

upheld by a fearless husband, who said, “I have fought all my life for a principle. If it is your conscience to go, I will not stand in your way.”

Like most pioneers of the past, Dr. Wiley did some things that seem questionable now. Systematically poisoning a group of healthy young men wouldn’t have won FDA approval today. But it’s thanks in part to him that there is an FDA. And it’s thanks in part to Anna Kelton Wiley that women won the right to vote. Now, that’s a Washington power couple we can celebrate.

Okay, time for some nice healthy chocolate!

UPDATE 10/24/2018: There’s a new biography of Dr. Wiley called The Poison Squad, by journalist Deborah Blum. Now (or, rather, after 2018 ends) I can find answers to all my questions about him, like did he really have the first serious automobile accident in Washington, D.C. history?

*But not all—the magazine ran an article the next month by Carrie Chapman Catt, President of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, called “Why We Did Not Picket the White House.”