I was going to write about women artists in honor of Women’s History Month, but then I opened the March 19, 1918, New York Times and saw that women were hatching international conspiracies all over Manhattan. Change of plan!

First, this:

Two men and two women were arrested, the Times reports, for alleged participation in an international German spy ring. The principal suspect is Despina Davidovitch Storch, the 23-year-old Turkish ex-wife of a French army officer. The Times said of Storch that

she is in appearance a strikingly handsome woman, and in the year that she made her home at the Waldorf-Astoria numbered among her friends many well-known persons, some of whom it was intimated yesterday are not at all anxious now to appear to have been among her admirers.

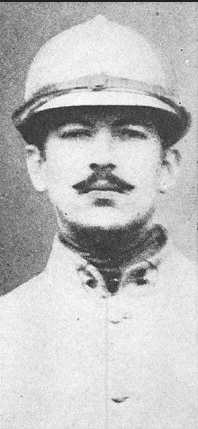

Mme. Storch was arrested in Key West with a young Frenchman, the Baron Henri de Beville, as the two were preparing to flee to Cuba. The Baron’s father, according to the apparently sympathetic Times, was “broken hearted as a result of his son’s arrest,” and felt that his son was “a victim of the ‘charms’ of the Turkish woman.”

(This account of masculine helplessness comes from a paper that, remember, wasn’t particularly sympathetic to women getting the vote.)

The pair had been living a peripatetic life. They were taken into custody in Madrid in 1915 as suspected enemy agents, sailed to Cuba after their release, and went on to the United States. They had also lived in Paris and Lisbon, where they amassed bills of $1000 a month. Their equally lavish New York lifestyle attracted the attention of the American authorities, who also found a safe deposit box in Mme. Storch’s name containing “a mass of foreign correspondence and a code.”

Their alleged co-conspirators were picked up in New York. Mrs. Elizabeth Charlotte Nix, who, according to the Times, “is about 40 years of age, but looks ten years younger,” had received a $3000 payment from the German ambassador before he left the country when war was declared, but she denied that it was a spy payment. The principal crime of “Count” Robert de Clairmont, as far as I can tell, was his dubious claim to his title.

The Justice Department official who announced the arrests, Charles F. De Woody,* recommended that the four suspects be deported to France. The problem with trying them in the United States was that—oops!—the espionage law only applied to men. President Wilson had mentioned this problem in his State of the Union address, and Congress was taking action, but not in time to go after Mme. Stroch and Mrs. Nix.

Meanwhile, down in Greenwich Village, a very different sort of (alleged) German-sponsored conspiracy was uncovered.

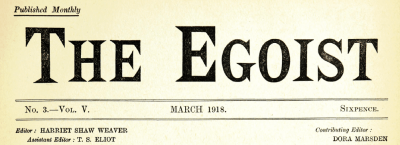

Agnes Smedley, the twenty-six-year-old “girl,” was arrested with Sailendra Nath Ghose, a “highly educated Hindu” who was already under indictment in San Francisco, for fomenting rebellion against British rule in India. (Uncharacteristically, the Times makes no mention of Smedley’s level of attractiveness.) Their activities were allegedly part of a “worldwide German-directed plot to cause trouble in India” and thereby weaken British war efforts. They sought assistance from several Latin American countries (Ghose lived for a time in Mexico, under the implausible pseudonym of Sanchez) and from Leon Trotsky.

“First women arrested in New York for enemy activities” might not be your idea of an inspiring Women’s History Month first. Well, then, there’s Annette Abbott Adams, the San Francisco-based Assistant U.S. District Attorney who spoke to the Times about the Ghose indictment. She would go on to be the first woman Assistant Attorney General and later a high-ranking California judge.

The indictment against Smedley was eventually dropped. She spent many years in China as a sympathetic chronicler of the Communist Party, and wrote a well-regarded autobiographical 1929 novel, Daughter of the Earth. She counted a Soviet spymaster among her lovers. She died in England at the age of 58, and is buried in Beijing.

As for Despina Storch…stay tuned! (UPDATE: Find out what happened to her here.)

*Even the bureaucrats in this story have picturesque names.