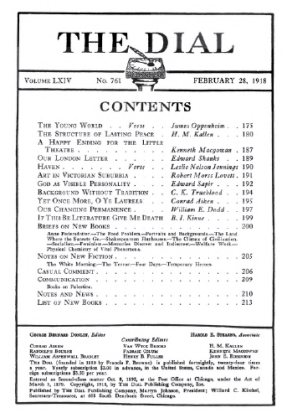

The writers who were reviewed in the modernist journals of 1918 are all long dead. But, when I read what T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and their fellow critics had to say about them, I can’t help cringing on their behalf.

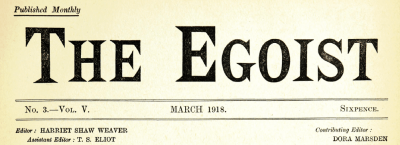

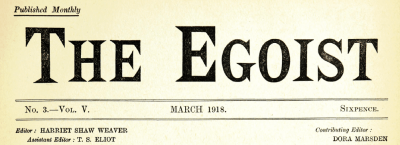

Take this review, in the March 1918 issue of The Egoist, of a collection called Georgian Poetry, 1916-1917. The reviewer, who calls himself Apteryx but is really T.S. Eliot, sums up the work of five contributors as follows:

Mr. Graves has a hale and hearty daintiness. Mr. Gibson asks, “we, how shall we…” etc. Messrs. Baring and Asquith, in war poems, both employ the word “oriflamme.” Mr. Drinkwater says, “Hist!”

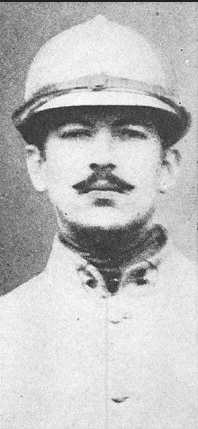

Robert Graves, 1914

These few sentences give us a good sense of what’s in the poems. Under the circumstances, though, this criticism seems a bit cruel. Robert Graves, who would go on to fame as a poet, novelist, and memoirist, was a 23-year-old soldier in 1918. “David and Goliath,” written in memory of his friend David Thomas, is a reversal of the Bible story, ending:

‘I’m hit! I’m killed!’ young David cries.

Throws blindly forward, chokes…and dies.

And look, spike-helmeted, grey, grim,

Goliath straddles over him.

Maurice Baring, Wilfrid Wilson Gibson, Herbert Asquith (the son of the Prime Minister), and John Drinkwater were older, in their thirties or forties, but they were all in uniform except Gibson, who tried to enlist but was turned down because of ill health.

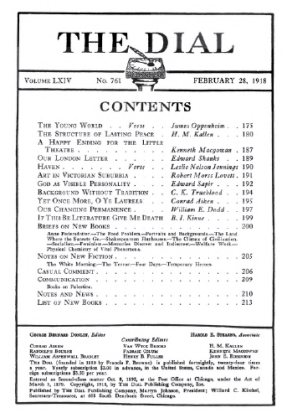

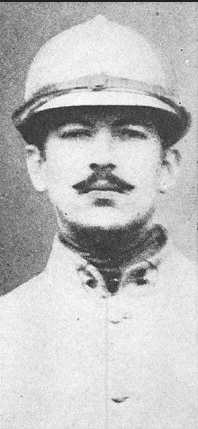

Alan Seeger

Even dying in the war didn’t spare a writer from The Egoist’s sharp scrutiny. The December 1917 issue included an unsigned review of a book of poems by Alan Seeger, who had joined the French Foreign Legion and died in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Seeger, best known now for the poem “I Have a Rendezvous with Death,” was a Harvard classmate of T.S. Eliot, who may have written the review.* (UPDATE 10/16/2019: Robert Crawford says in his biography Young Eliot that he did.) According to the Egoist,

Seeger’s poems are not unworthy of the attention they have attracted. The book has not much to offer to the small public which wants nothing twice over, but it has a good deal to give to the public which will take what it likes in any amount.

The Egoist was dismissive toward popular novelists. In a discussion in the February 1918 issue of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, reprinted from an Italian publication and apparently translated by Joyce himself, Diego Angeli says:

To tell the truth, English fiction seemed lately to have gone astray amid the sentimental niceties of Miss Beatrice Harraden, the police-aided plottiness of Sir Conan Doyle, the stupidities of Miss Corelli or, at best, the philosophical and social disquisitions of Mrs. Humphrey Ward.**

Across the Atlantic, The Dial, which wasn’t a modernist journal but had modernist sympathies,*** shared The Egoist’s contempt for popular novelists. You don’t really have to read further in B.I. Kinne’s review of Hugh Walpole’s The Green Mirror than the title: “If This Be Literature Give Me Death.” If you do, you’ll read that

Mr. Walpole’s most irritating fault is his adherence to the court reporter’s method of observing and recording. This is the fault of many of the contemporary novelists. It is their belief, apparently, that the mere writing down of lists of things, whether dishes of food, toilet articles on the heroine’s dressing-table, books and objects d’art on the drawing-room tables, or the furnishings of a room, constitutes vivid literature.

Hugh Walpole, 1915 (The Independent)

The modernist critics reserve their most scathing criticism for literary luminaries. In an article on Henry James (whom he admired) in the January 1918 Egoist, Eliot writes that G.K. Chesterton’s “brain swarms with ideas; I see no evidence that it thinks.” Ezra Pound, also writing admiringly about James in the same issue, says of recent writing that

we may throw out the whole [H.G.] Wells-[Arnold] Bennett period, for what interest can we take in instruments which must of nature miss two-thirds of the vibrations in any conceivable situation.

The modernists’ criticism may be harsh, but, unlike H.L. Mencken’s, it doesn’t seem mean-spirited. Eliot and Pound and the other modernist critics took their work with tremendous seriousness. They thought that the ossified literary world of their time had to die, and that it was their job to kill it. They didn’t just rip into bad writing; they explained how it exemplified what was wrong with the literature of the day. And they had a vision of what should come in its place: modernist writing by the likes of Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, and of course themselves.

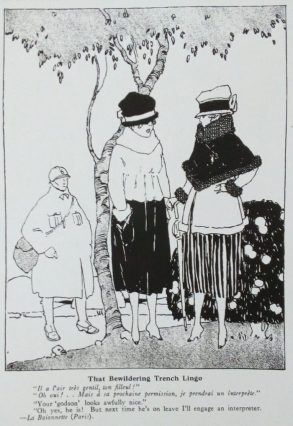

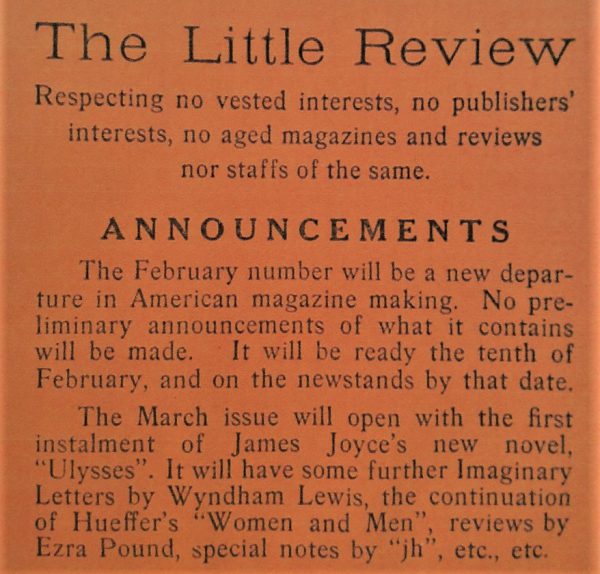

This wasn’t exactly trench warfare, but it had its risks. Eliot reported in the March 1918 Egoist that the October 1917 issue of the American modernist journal The Little Review had been declared obscene and seized by the post office, the offending item being a story by Wyndham Lewis. The journal’s legal complaint against the post office had failed.****

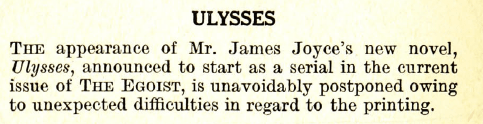

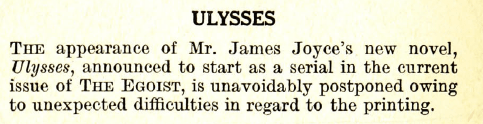

The March 1918 issue of the Egoist contained the following announcement:

That is, no printer in England would touch it. But it was scheduled to be serialized in the Little Review as well.

Bigger battles lay ahead.

*He was also folk singer Pete Seeger’s uncle.

**See! I told you!

***It later became a modernist journal, and was the first place “The Waste Land” was published in the United States.

****The story was called “Cantleman’s Spring-Mate.” Naturally, I immediately tracked it down. Summary: a young man about to go to war sees animals rutting all around, joins in the action with a village girl, and feels that he has defeated death. (Except that makes the story sounds life-affirming, which it’s not. It’s modernist!)