There seems to be a pattern: when something bad happens in 2018, it turns out that a similar, but way worse, thing happened on the same day in 1918. First the cold weather, now the shutdown.

Believe me, I know how bad a government shutdown is—I went through several of them during my Foreign Service career. But on January 21, 1918, half the country shut down.

The problem: ships full of war supplies destined for Europe were sitting idle because they didn’t have coal to fuel them. The fuel couldn’t get through because of congestion on the railways. So, on January 16, Fuel Administrator Harry Garfield ordered manufacturers east of the Mississippi and in Louisiana and Minnesota to shut down for five days beginning on January 18. In addition, all business establishments, with a few exceptions, were ordered to shut down for the next five Mondays.

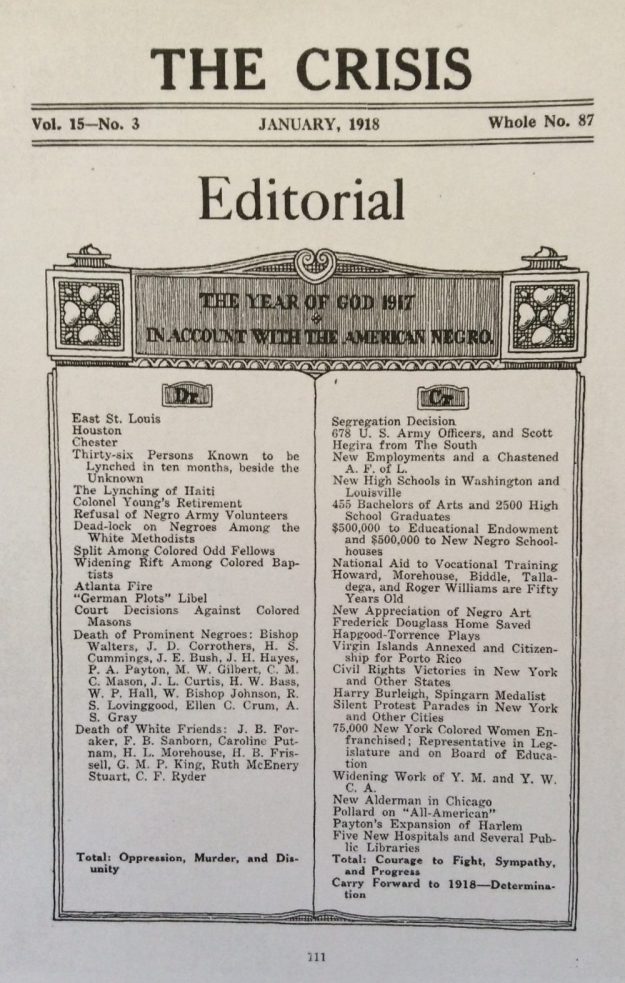

Harry Garfield, ca. 1911

The order, according to the New York Times, “came with an abruptness which left official Washington gasping.” Surprisingly, not many people asked, “What gives you the right to do this? You’re the fuel administrator, not the economic commissar.” But there were a lot of objections. The Times editorial page questioned Garfield’s competence, saying that “chloroforming a nation to spare it the pangs of hunger is not good therapeutics, it is malpractice.” The Senate, which was controlled by the Democrats but you’d never know it by the way they treated President Wilson, voted 50 to 19 in favour of a resolution requesting suspension of the order for five days to allow time to evaluate it. Too late! By the time the resolution was approved at “6:05 o’clock,” Garfield had signed the order and it “was flashed to every city in the country.” The Times noted that, after a day that “had been enough to try to nerves of every one,” Garfield seemed unperturbed. (It could be that, having been an eyewitness to the assassination of his father, President Garfield, at age 17, nothing seemed all that bad after that.)

In response to objections that workers would lose their wages, Garfield suggested that their employers could pay them. The board of U.S. Steel, though, decided that this was not such a good idea. Chairman E.H. Gary, who, according to the Times, “did one of the hardest day’s work in his busy life,” said that to pay idle workers “would establish a precedent that would eventually be unfair to the employer and the employe.” The New York State Federation of Labor estimated that 80 percent of the state’s 600,000 workers would lose their pay during the shutdown.

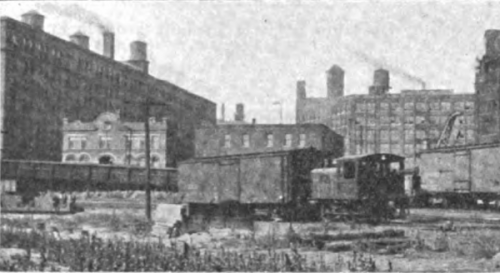

Railway Age

For the first few days, things went all right. More coal was making its way to the ports, despite freezing temperatures and snowstorms. But then came the first Monday shutdown. Disaster! Federal officials had mobilized longshoremen to unload the thousands of tons of coal that had been rushed to the piers, but they were stopped by police and soldiers because they didn’t have photo IDs. The rule requiring the IDs wasn’t supposed to go into effect until February 1, but it was implemented early because of bomb threats. By the time it was lifted, most of the workers had gone home. Meanwhile, merchandise that arrived by train couldn’t be moved out of the rail yards to make room for the coal because, oops, the department store warehouses they were destined for were closed under Garfield’s order. The result of all the chaos: less than half the normal daily supply of coal arrived in New York.

At least the idle workers had something to entertain them. Theaters had been given permission to stay open on Mondays and close on Tuesdays instead. On the first workless Monday, it was standing room only in the theaters and the vaudeville, motion-picture, and burlesque houses.