A couple of months into this project, I was chatting with my 13-year-old nephew during an outing to Simon’s Town, a coastal village south of Cape Town. He’s a YouTuber, and we were talking about building an audience. He had a bigger following than I did, and I was hoping he could give me some tips.

“What do you write about again?” he asked me.

“Things that happened a hundred years ago,” I said.

“Kids don’t care about that,” he told me.

“I don’t write for kids,” I said.

“Who do you write for?” he asked. “Old people?”

“Yes,” I said.*

“Then you should write about things that old people care about, like Mandela,” he said.

Four months later, on the 100th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s birth, I’m taking his advice.

A baby being born in a village in the eastern Cape is not the stuff of international headlines, of course, so I can’t tell you about the birth itself. I can tell you, though, about the South Africa Nelson Mandela was born into and would grow up to transform.

With war raging in Europe, the outside world wasn’t paying much attention to South Africa. There was a fascinating article about the country’s “native problem,” though, in the December 8, 1917, issue of the New Republic. It was written by R.F. Alfred Hoernlé, who, despite his Afrikaans-sounding last name, was a British academic (with a German grandfather) who had taught for three years at what is now the University of Cape Town.**

Hoernlé gets to the crux of the problem right away:

The native problem dominates the South African scene. Whatever political issues and movements show in the foreground, it supplies the permanent background. However much the white population of South Africa may be absorbed in the racial*** and economic rivalries of the immediate present, it cannot but be profoundly apprehensive about its future, as long as the native problem remains unsolved.

Hoernlé points out that

Though in name a democracy, South Africa is in fact a small white aristocracy superimposed on a large native substratum.

Not that he’s advocating anything crazy, like making it a real democracy.

It is not a question, mainly, of the natives’ present unfitness for the vote, which everyone must readily grant.**** It is a question of political development. No policy which would ultimately involve that the white should admit the mass of the blacks to political power has any chance of acceptance, on the face of the unalterable numerical superiority of the blacks.

So what to do?

To that question a speech which General [Jan] Smuts delivered in London, in May of this year, furnishes an answer. He rightly characterizes the problem as one of maintaining “white racial unity in the midst of the black environment.” This depends, in part, on avoiding two mistakes, viz., mere exploitation of the natives, and racial intermixture. The white races, Smuts insists, must strictly observe the racial axiom, “No intermixture of blood between the two colors,” and the moral axiom, “Honesty, fair-play, justice, and the ordinary Christian virtues must be the basis of all our relationship with the natives.”*****

And how does Smuts plan to achieve this? Hoernlé tells us that

Any incorporation of the black into the structure of white society is bound to raise, in the long run, the problem of admitting them to citizenship, giving them the vote, and treating them as the white man’s political equals. There is only one way of avoiding this result, and that way is segregation of the native—the creation of the land in a chequered pattern of white and black areas. This is the policy to which General Smuts pins his hopes…

The idea is, wherever there are large bodies of natives, to assign to them definitive areas within which no white man may own land. The native, on his side, is to be forbidden to own land in white areas, though he is to be free to go and work for the white man. The races having been thus territorially separated, each is to live under its own political institutions…

A beginning has so far been made by the Natives’ Land act of 1913, a purely temporary measure designed chiefly to prevent speculation in land in anticipation of later legislation.

That’s one take on the Natives Land Act. Another comes from black writer and activist Sol Plaatje, who wrote in the 1914 classic Native Life in South Africa that

Awaking on Friday morning, June 20, 1913, the South African native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.

The Natives Land Act prevented South Africans from buying land in 93% of South Africa. It would also have disenfranchised non-white voters in the Cape, the only place where they had the right to vote (some of them, that is—there were education and property qualifications), but the courts struck that provision down. As far as the law’s “purely temporary” nature goes, its impact continues today: under post-apartheid land restitution legislation, South Africans have the right to claim land taken from their ancestors only after its passage.

Hoernlé calls the partition/self-determination scheme “promising in principle.” The challenge, he says, is to come up with a fairer division of land than the one proposed by a recent commission, which allocates South Africa’s five million black inhabitants a little over 12% of South Africa’s territory and reserves the rest to the 1,250,000 whites. (This was exactly the breakdown when the black “homelands” were created during apartheid.)

If the “natives” are treated justly, Hoernlé said, there is a path to peace. But he’s not hopeful.

At present, the eye that would pierce the future, sees the deepening shadow of the native problem creep slowly but surely over the sunny spaces of South Africa.

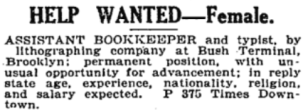

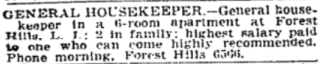

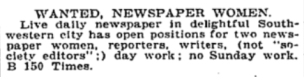

People often ask me if 1918 reminds me of our world today. For the most part it doesn’t, at least as far as the United States is concerned. There are similarities, of course, but a country where lynchings were commonplace and women couldn’t vote and want ads specified Christians only is, thankfully, not one I recognize. The South Africa Hoernlé describes, on the other hand, differs hardly at all from the country I arrived in as a young diplomat in 1988.

It would take over seven decades for the South Africa Mandela was born into to change fundamentally—decades during which he would grow up, become a lawyer, join the liberation struggle, spend 27 years in prison, and emerge to lead his people to freedom.

*No offense! The baseline here is 13.

**UPDATE 11/09/2019: Hoernlé popped up in Young Eliot, Robert Crawford’s biography of T.S. Eliot. He taught Eliot as a visiting professor at Harvard and later joined the Harvard philosophy faculty. Hoernlé was a (laudatory) reviewer for Eliot’s Ph.D. dissertatation and was chair of the philosophy department when it considered, but ultimately decided against, offering Eliot a position.

***That is, English vs. Afrikaner.

****“Everyone” meaning whites, of course. Black South Africans don’t have a say in this matter because…well, they don’t have the vote. (Mostly. We’ll get to that.)

*****Jan Smuts was the Woodrow Wilson of South Africa, renowned statesman abroad and racist at home. He was considered a liberal in South Africa, which gives you an idea of why “liberal” remains a swear word among black South Africans today.