Three-quarters of the way through 1918, everything seems normal to me now.* Appalling a lot of the time (racism, eugenics, anti-Semitism, class snobbery), but normal. Nine months of immersion have broken down the barriers of aesthetics and language use. I now think of people as being the age they were in 1918. Happy August/September birthdays to Dorothy Parker (25), T.S. Eliot (30), and William Carlos Williams (35), youngsters all!

I didn’t do a Best and Worst for August because I was back in the United States, socializing nonstop. I don’t know how those 1918 rich people did it—it’s exhausting!** By the time I got back to Cape Town and emerged from the fog of jet lag, September was halfway gone. Which October will be too if I don’t hurry up. So, without further ado, the best and worst of August and September 1918!

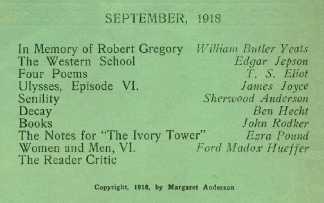

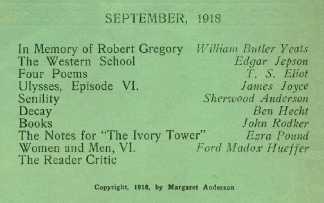

Best Magazine: The Little Review, September 1918

Just look at the table of contents of the Little Review’s September issue. It’s the literary equivalent of the Yankees’ 1927 starting lineup.***

Of course, another possible analogy is to one of those movies so overstuffed with stars that you just know it’s going to be horrible.

So which is it?

Somewhere in between. Yeats’s “In Memory of Robert Gregory,” mourning the death of the son of close friends in an aviation accident in Italy (or maybe it was friendly fire), sounds like outtakes from “Easter 1916,” but so-so Yeats is better than just about anyone else at the top of their game. The Eliot poems include his notoriously anti-Semitic “Sweeney Among the Nightingales” (“Rachel née Rabinovitch/Tears at the grapes with murderous paws”), but also a poem in French, “Dans le Restaurant,” part of which eventually made its way, in English, into “The Waste Land.” I confess that I haven’t kept up with the Ulysses serialization, but, hey, it’s Ulysses.

So more 1927 Yankees than New Year’s Eve. And there are more accolades for this issue to come—keep on reading!

Worst Magazine: Current Opinion, September 1918

Halfway through the September issue of The Bookman, I was convinced we had a winner. The magazine, under a new owner, had undergone its second major revamp of the year, and 1918 magazines revamps are never a good thing. They just make the magazine more like all the other magazines. The old Bookman was fusty, but it was entertaining. In the new Bookman, most of the article aren’t even about books. If they are, they’re about old books like Tom Jones or boring books about “Sea Power Past and Present.” But then the magazine redeems itself with an Amy Lowell love poem**** and an excerpt from the upcoming sequel to Christopher Morley’s fun 1917 novel Parnassus on Wheels. And they kept “The Gossip Shop,” which, although most of the gossip is about which writer got his commission and is shipping off to France, is still kind of fun. So I felt better about The Bookman but was left without a worst magazine.

Then I came across the September issue of Current Opinion, featuring an article called “Why the Jew is Too Neurotic.” The reason is explained in the sub-head: “Because his Extraordinary Resemblance to the Average Spoiled Child Causes Mental Strain.” The rest of the article isn’t as bad as that makes it sound. Something about how the Jews were the favorite children of God, and were isolated from the rest of society, and…I’ll spare you the psychoanalytic logic. And there’s sympathetic discussion of anti-Jewish discrimination throughout the ages. But the article epitomizes what’s worst about 1918: the tendency to lump together entire “races” (African-Americans, Jews, Germans, Czechoslovakians, whoever) and ascribe a common set of qualities to them. Inconsistency alert: the issue also includes an admiring profile of New York Times owner Adolph Ochs, who comes across as a gee-whiz regular guy and not neurotic at all.

Best Line in an Editorial: “Vardaman Falls,” New York Times, August 22

I’m not a fan of 1918 NYT editorials, which are generally narrow-minded, prejudiced, and smug. But this one, a gloating account of the primary election defeat of Senator James Vardaman, one of the worst racists in congressional history (although that didn’t bother the Times nearly as much as his antiwar stance), has my favorite 1918 sentence so far:

Was he the victim of his own singularity, grown megalomaniacal, or did he simply overestimate the hillbilliness of his state?

Least Prescient Literary Criticism: Louis Untermeyer, “The Georgians,” The Dial, August 15

Louis Untermeyer, ca. 1910-1915, Library of Congress

It’s not really fair, with the benefit of hindsight, to poke fun at predictions by past critics about how future critics will regard their own times. But it’s fun! So let’s!

Louis Untermeyer, who was actually one of the best critics of the era as well as being a noted poet himself, ruminates on this topic in a review of the anthology Georgian Poetry: 1916-1917. He says of the anthologized poets that “these men of what he [the future critic] will doubtless call the 1920s” will say that the Georgians “produced a literature as distinctive and even more human than their [Elizabethan and Victorian] predecessors.”

No they won’t, Louis. And we don’t call the 1910s the 1920s. We call them the 1910s.

Specifically, Untermeyer predicts that the future critic

will have a vigorous chapter on the invigorating vulgarisms of Mansfield and an interesting essay on Lascelles Abercrombie, who he will find, in spite of the latter’s too packed blank verse, to be even more “modern” than the author of “The Everlasting Mercy.”

Um, not quite. What’s really going to happen, Louis, is that T.S. Eliot***** and the modernists are going to wipe these guys off of the map. Which brings us to…

Most Prescient Literary Criticism: Edgar Jepson, “The Western School,” The Little Review, September

National Magazine, April-September 1915

Continuing our September 1918 Little Review/1927 Yankees starting lineup analogy, Edgar Jepson is, say, Tony Lazzeri to Eliot’s and Joyce’s Ruth and Gehrig. In his article “The Western School,” Jepson, a British writer of detective and adventure fiction, complains about the undue accolades being given to subpar work by prominent poets. He makes his case convincingly by quoting these lines by Vachel Lindsay:

And kettle-drums rattle

And hide the shame

With a swish and a swirk

and dead Love’s name

and these from “All Life in a Life” by Edgar Lee Masters:

He had a rich man or two

Who took up with him against the powerful frown

That looked him down

For you’ll always find a rich man or two

To take up with anything–

There are those who want to get into society, or bring

Their riches to a social recognition

and these from “Snow,” a long poem by Robert Frost about some monks having a conversation in the middle of the night:

That leaf there in your open book! It moved

Just then, I thought. It’s stood erect like that,

There on the table, ever since I came,

Trying to turn itself backward or forward—

I’ve had my eye on it to make out which…

But don’t despair for poetry! For, Jepson says,

the queer and delightful thing is that in the scores of yards of pleasant verse and wamblings and yawpings which have been recently published in the Great Pure Republic I have found a poet, a real poet, who possesses in the highest degree the qualities the new school demands.

None other than…T.S. Eliot!

Could anything be more United States, more of the soul of that modern land than “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”?… Never has the shrinking of the modern spirit of life been expressed with such exquisiteness, fullness, and truth.

Jepson also praises Eliot’s “La Figlia Che Piange” (“Weave, weave the sunlight in your hair”), saying that

it is hardly to be believed that this lovely poem should have been published in Poetry in the year in which the school awarded the prize [Poetry magazine’s Levinson prize] to that lumbering fakement “All Life in a Life.”

Jepson may be overstating his role in the discovery of Eliot, who, after all, is in plain sight in that very issue. But he deserves credit for his prescience, especially since he also complains about Lindsay’s “Booker Washington Trilogy” in language straight out of the #OwnVoices movement:

I have a feeling that it is rather an impertinence. Why should a white man set out to become the poetic mouth-piece of the United States blacks? These blacks have already made the only distinctively United States contributions to the arts—ragtime and buck-dancing. Surely it would be well to leave them to make the distinctively United States contribution to poetry.

Home run for Tony Lazzeri!

Best Magazine Cover of a Woman Swimming with a Red Scarf on Her Head:

In this surprisingly competitive category, here are the runner up

and the winner.

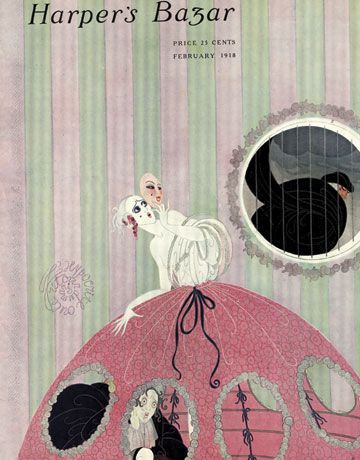

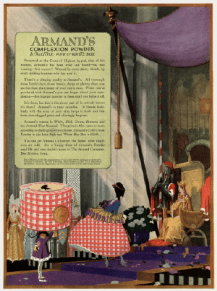

Best Ad Depicting the Advertised Item as Humongous

Winner:

Harper’s Bazar, September 1918

Runner-up:

Good Housekeeping, August 1918

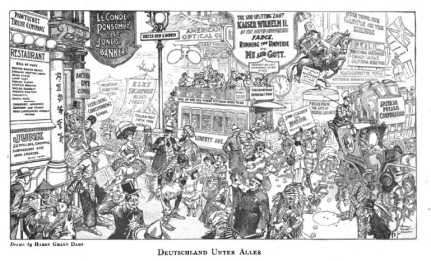

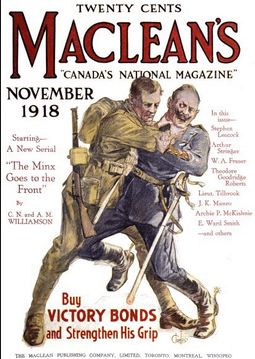

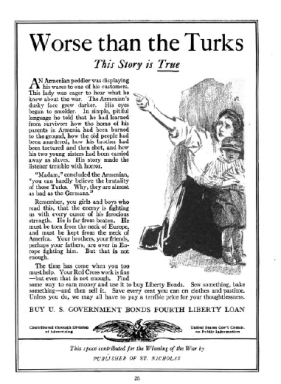

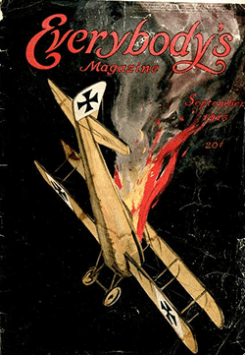

Worst Magazine Cover:

At the risk of sounding like a Boche sympathizer, this is just mean.

Everybody’s, September 1918

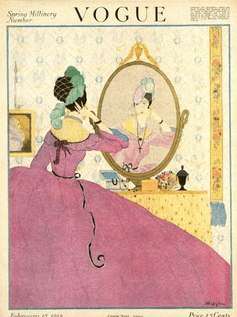

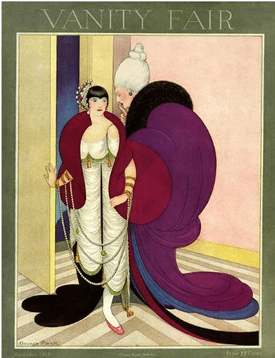

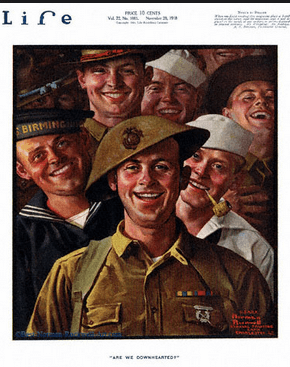

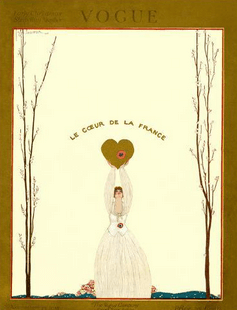

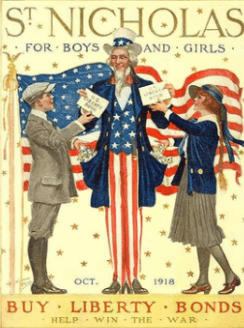

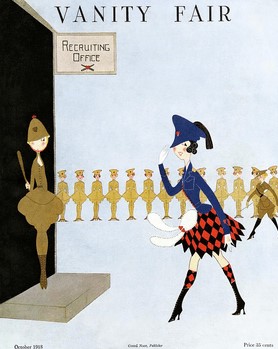

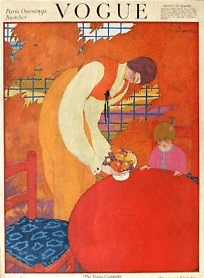

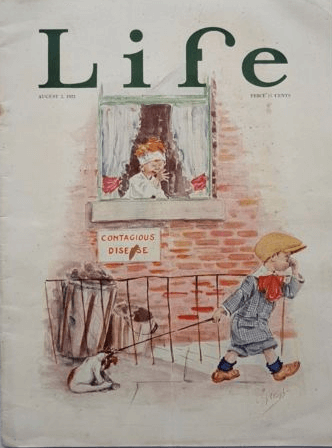

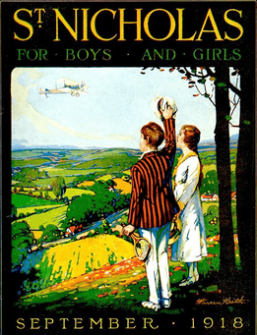

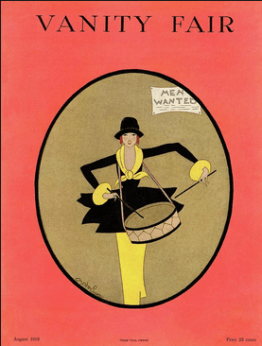

Best Magazine Cover:

There are a lot of worthy contenders, like this

St. Nicholas, August 1918

and this

Vanity Fair, August 1918

and this startlingly modern-looking one

House & Garden, August 1918

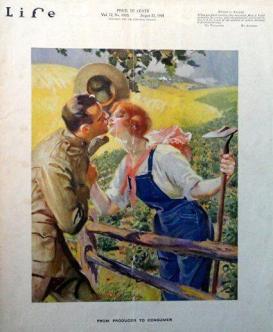

and this, which, in another month, might have won.

Vogue, August 1, 1918

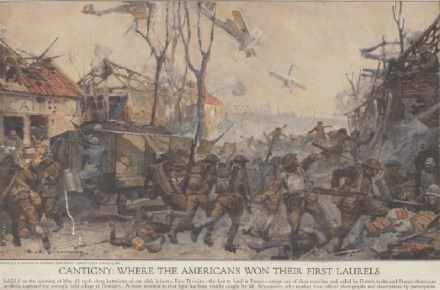

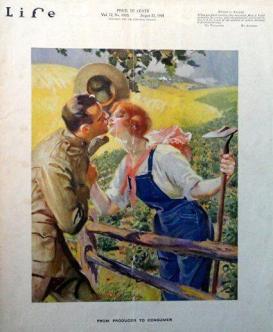

But the war was intensifying, American casualties were mounting, and it seems wrong not to recognize that. So here’s the winner, a soldier saying good-bye to his farmerette sweetheart.

Life, August 22, 1918

On to October!

*Of course, I might feel differently if I had to wear a corset.

**Although not as exhausting as working in a Lower East Side textile factory all day and then going to night school.

***Ford Madox Hueffer is Ford Madox Ford, remember.

****To her female lover. Which may not have been clear to her audience, although does “quiet like the garden/And white like the alyssum flowers/And beautiful as the silent spark of the fireflies” sound like a man to you?

*****Whom, to be fair, Untermeyer mentions later in the article. He says that the future critic will realize “in the light of the new psychology” how much prose writers like J.D. Beresford, Gilbert Cannan, A. Neil Lyons, Rebecca West and Thomas Burke had in common with “such seemingly opposed verse craftsmen” as Edward Thomas, W.W. Gibson, Rupert Brooke, James Stephens, and T.S. Eliot. If you blah-blah-blah out the writers no one reads today, we’re left with “Rebecca West has something in common with Rupert Brooke and T.S. Eliot.” I’ll give him that. Kind of.