When I was in the Foreign Service, living in Cambodia or Honduras or wherever, people used to ask, “But don’t you miss home?” I never knew what to say. The honest answer was, “I miss some things, sometimes, but it’s way more interesting here. Don’t you get bored living in the same place all the time?” That seemed kind of rude, though.

A quarter of the way through, that’s how I feel about my life in 1918. I’ll see, for example, that Meg Wolitzer, Curtis Sittenfeld, and Rebecca Harrington all have books coming out, and for a second I’ll wish that I could read them, but then I’ll pick up Mrs. Spring Fragrance or the latest issue of The Dial, and the feeling goes away. I can read those books next year. In the meantime, it’s way more interesting here.

Now for the best and worst of March 1918:

Best Magazine: The Little Review

Ulysses, as I wrote earlier this month, made its first appearance in the Little Review in March 1918. The issue also includes Ezra Pound writing on Marianne Moore, fiction by Wyndham Lewis, and an essay by Ford Madox Hueffer (a.k.a. Ford) that contains the sentence “The Englishman’s mind is of course made up entirely of quotations.” But the rest of the issue could have been blank (which wouldn’t have been unprecedented—the first thirteen pages of the September 1916 issue were blank, an expression of editor Margaret Anderson’s frustration over the lack of quality submissions) and it still would have been the best magazine of the month, if not the year.

Worst Magazine: The Art World

The Art World, as I noted last week, had nothing good to say about impressionism or anything that came after. To put that into perspective, the first major exhibition of impressionist art was in 1874. So an art magazine taking this stance in 1918 is like Rolling Stone saying in 2018 that this rock-and-roll music is just a lot of noise.

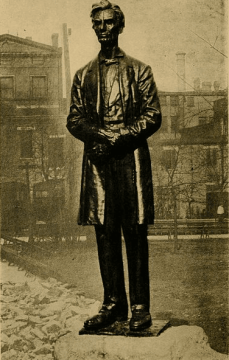

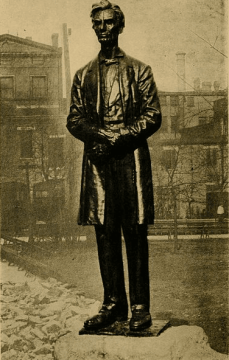

Statue of Lincoln, George Grey Barnard, Lytle Park, Cincinnati (1917)

In its March 1918 issue, the last before it merged into another magazine, The Art World criticized George Grey Barnard’s statue of Lincoln in Cincinnati, saying that Barnard

does not show the majestic Lincoln at the bar of history being judged and admired, but a slave Lincoln at the block, being sold and pitied…let us hope that Mr. Barnard will now deign to accept the advice we gave him in June 1917 and make a new Lincoln—virile, heroic, and majestic.

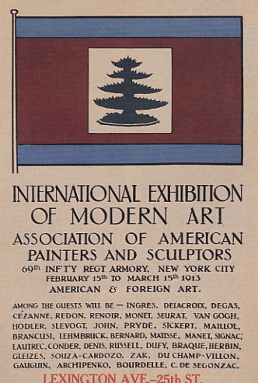

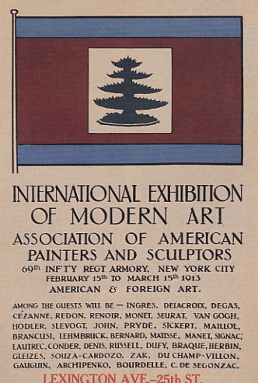

The magazine approvingly quotes portraitist Cecilia Beaux saying of the 1913 Armory Show in New York, the first large exhibition of modern art in the United States, that

“It was like a sudden windstorm that raises no little dust, noise, and confusion for the moment; when the wind dies down you discover that much that was of no real value has blown away, leaving a clearer, wholesome atmosphere.”

The Art World branches out to the written word in this issue, calling a modernist poem “speech worthy of a yapping maniac.”

Best humorous essay: “Making the Nursery Safe for Democracy,” by Harold Kellock, The Bookman

Essays about family life in 1918 are generally steeped in sarcasm (if they’re by men) or sentimentality (if they’re by women). It’s hard to find a family that seems real. Then I came across Harold Kellock’s essay about his four-year-old son being bombarded with royalist propaganda through his nursery reading. Every night, Kellock is forced to read his son a story about some heroic king. “In a world wherein we are pouring out our blood and treasure that democracy may live safely,” he complains, “our children scarcely out of the cradle are being made into staunch little monarchists.” He takes a stab at democratizing the stories, but it doesn’t work, and he resigns himself to nursery royalism.

“Then,” I read, “the king took Gretel to his palace and celebrated the marriage in great state. And she told the king all her story, and he sent for the fairy and punished her.” Think of having the power of punishment over fairies! The King und Gott! But my son swallows it complacently. He does not question the divine right of kings.

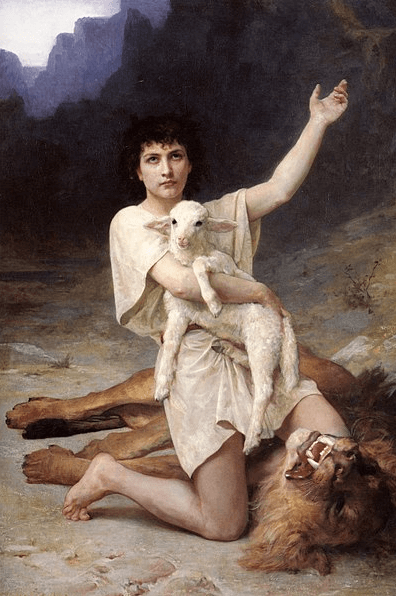

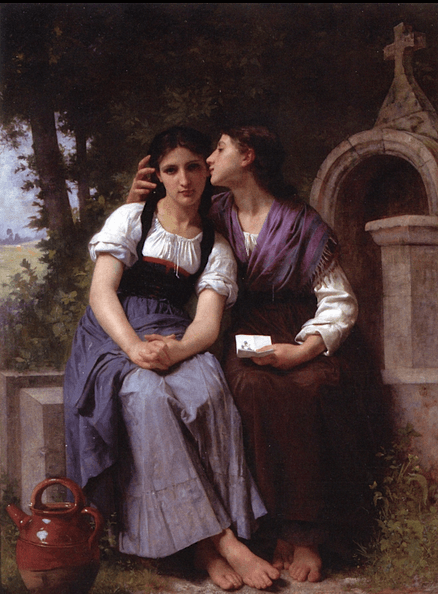

Faery Tales from Hans Christian Andersen, Maxwell Armfield, 1910

Kellock reassures himself that, when the time comes, he can turn his child into a democrat by showing him photographs “of some vacuous king, discreetly bearded to hide his recessional features,” or “a typical princess, whose hat and features alike seem so unfortunately chosen, opening a Red Cross bazaar.”

But not for a while, he says.

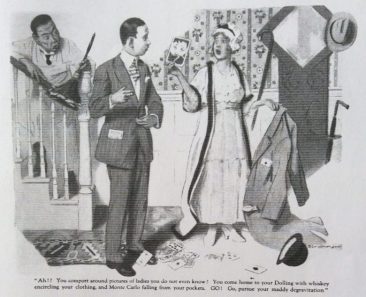

Worst humorous essay: “I Must Have Been A Little Too Rough,” by George B. Jenkins, Jr., Smart Set

I hope this is the worst thing I read all year. There must be an anti-gender violence message hidden somewhere, but…well, read it for yourself.

I must have been a little too rough.

“Women,” her father had told me, “are tired of the courteous treatment of the average man. They are bored by the vapid compliments, the silly lies, the stupid chatter of pale youths with gardenias in their lapels. If you want to be a success with women, be rude! Be violent! Overpower them, assert your physical superiority! If necessary, beat them!” He became quite excited. “Pound them! Assault them! Half-murder them!”

I listened to him respectfully, though I did not care for him at all. Yet I believed him, for he is notoriously successful in his affaires.

I decided to test his theories. Striding into the next room, I grasped his daughter about the waist.

“I love you!” I roared, squeezing her until her face was purple.

“You belong to me!” I shouted, dragging her around the room by her hair, and overturning several chairs in our progress.

“Damn you!” I shrieked, striking her on the shoulder, where the blow left a blue welt, “I will fight the world for you.”

She began to whimper.

“Shut up!” I ordered, in my rudest manner, and slung her across the room.

But I must have been a little too rough, for she fell out the window.

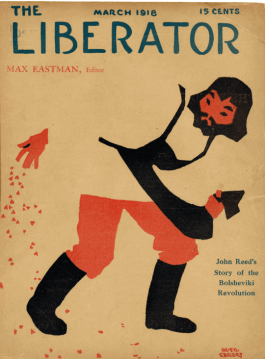

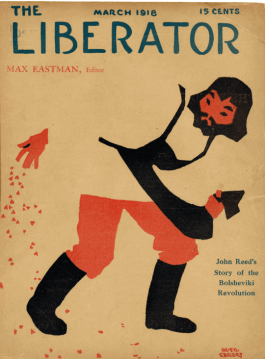

Best magazine cover: The Liberator

The first issue of The Liberator was published in March 1918. Its predecessor, The Masses, had closed down in 1917 after being declared treasonous by the government for its anti-war stance. The debut issue included reporting from Russia by John Reed, whose Ten Days that Shook the World was published the next year (and who died in Russia in 1920 at the age of 32). I’ll write more about The Liberator later. For now, here’s its inaugural cover, by Hungarian-American artist Hugo Gellert.

Worst magazine cover: Collier’s

I’m imagining the meeting where this cover was conceived.

Art director: How about…the President?

Editor: What would he be doing?

Art director: Nothing, just a picture of his face, in black and white. With a caption that says [stretches his hand into the air dramatically], “The President.”

Editor: I like it!

Best humor:

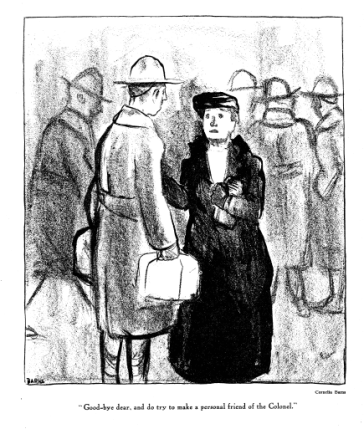

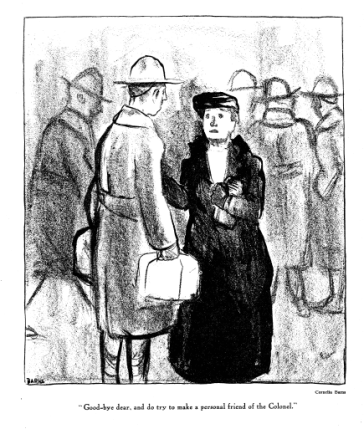

As I’ve noted before, there are no good jokes in 1918 magazines. But I liked this Cornelia Barns Liberator cartoon, featuring the world’s most coldhearted mother seeing her son off to war.

Worst humor:

First dog: How is brother collie over there? Is he in your set?

Second: Oh, yes; we visit the same garbage pails.

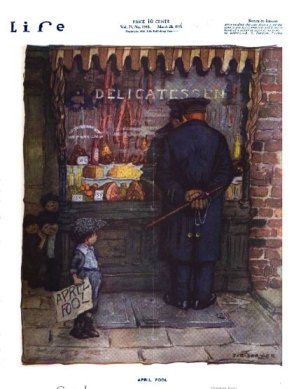

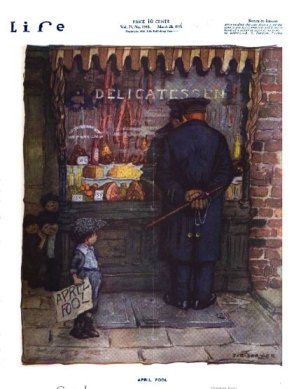

(Life magazine, March 28, 1918)

And, in honor of Women’s History Month, the most inspiring women:

I came across so many! Novelists Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, and Mary Roberts Rinehart; artist Elizabeth Gardner; dancer Irene Castle; Little Review editor Margaret Anderson; suffragist Anna Kelton Wiley; prosecutor Annette Abbott Adams; rebellious housewife Julia Clark Hallam; and the anonymous woman who wrote about how divorce saved her sanity.

But every month is Women’s History month at My Year in 1918, and there are lots more inspiring women to come. (Sneak preview: a pioneering British sexologist and a witty Chinese-American writer.) On to April!