I made it! One month of reading books, magazines, and the news as if I were living in 1918. It’s been even more fun than I expected. The 1918 New York Times at breakfast, printouts of The Dial and The Egoist for on-the-go reading, and Edith Wharton at bedtime. I don’t miss 2018 at all.

Here are some of the month’s highs and lows.

Best magazine: The Crisis

The Crisis, January 1918, Frank Walts

I expected the NAACP’s magazine, edited by W.E.B. Du Bois, to be historically interesting. It was–and it also turned out to be the month’s most compelling read, full of top-quality explanatory journalism, social criticism, personal essays, and fiction.

Runner-up: The New Republic. When I’m befuddled by something I read about in the New York Times—like, was the American war effort as pathetic as Wilson’s critics make it sound, or did Harry Garfield really have to shut down the entire East Coast—all I have to do is wait a few days and the New Republic will provide a clear, convincing explanation. And then explain it again. And then, in case I still don’t get it, spend another couple of pages making the same point. Illuminating? Yes. Concise? No.

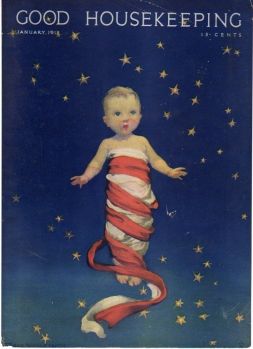

Worst magazine: Good Housekeeping

Good Housekeeping, January 1918, Jessie Willcox Smith

Good Housekeeping was already in the lead for this category because of the horrible Marie Corelli article about cleansing the world through eugenics. Then I read “Mirandy on the One We Didn’t Marry,” by Dorothy Dix. I knew of Dix as a pioneering advice columnist. I’m a big fan of advice columns, and I was eager to find out what she had to say to the women of 1918. But Mirandy turns out to be Dix’s monthly impersonation of an African-American woman who provides her views on life in heavy dialect. “Ef you ’grees wid a woman ‘bout her husban’s faults an’ weaknesses she is lak enough to up an’ lambast you wid de fust thing dat is handy,” Mirandy says. There’s an illustration of a kerchiefed woman with an umbrella giving a talking-to to her pop-eyed friend. If you want to hear a real African-American woman’s take on family life, check out the lovely “A Mother’s New Year’s Resolutions” by Josephine T. Washington, in, where else, The Crisis.

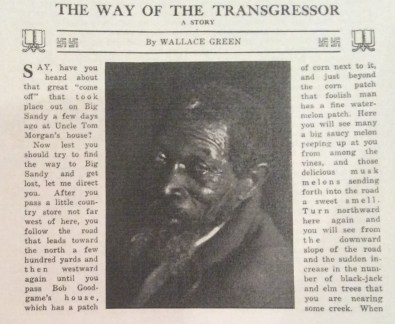

Best short story: “The Way of the Transgressor,” by Wallace Green

The Crisis, January 1918

I wrote about this story, which ran in the January 1918 issue of The Crisis, earlier this month. It’s vivid, unformulaic, funny, and moving. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find out anything about Green (if that was his real name), or to find anything else that he wrote. I’ll keep looking.

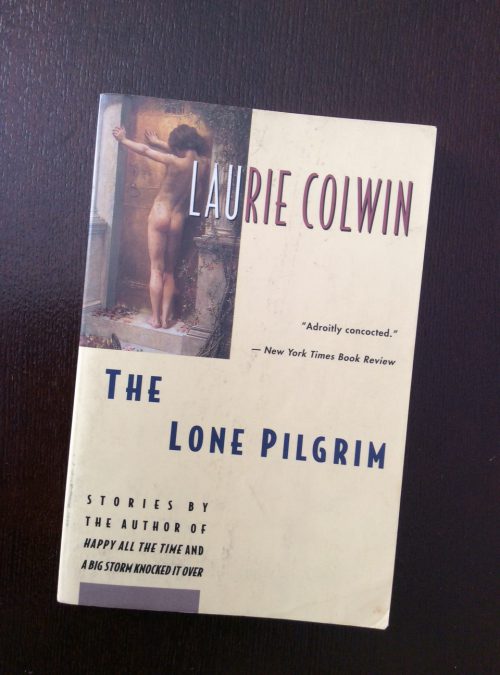

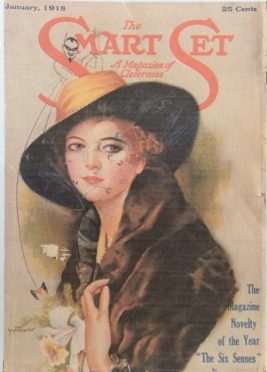

Runner up: “The Policewoman’s Daughter,” by Ben Hecht (Smart Set, January 1918). Agatha is an innocent young woman with a domineering mother (a figurative, not a literal, policewoman), and the story takes place entirely in her head as she waits in the parlor of a seedy hotel for an assignation with a violinist. As the minutes tick by and it becomes clear that he isn’t going to show up, she falls into a state of anguish, followed by relief that God has saved her from ruin. Then she realizes that she got the date wrong, and her joyful anticipation returns. Hecht, who was twenty-three when this story was written, would go on to be one of Hollywood’s top screenwriters. His many credits include His Girl Friday, which is one of the talkiest films ever made. In “The Policewoman’s Daughter,” no one says a word. Talk about versatility!

Worst short story: “A Palm Beach Honeymoon,” author unknown

I opened up Vanity Fair and, after 23 pages of ads, seven of them for dogs, finally got to some editorial copy. Or so I thought. “A Palm Beach Honeymoon” is the story of, well, a Palm Beach honeymoon. Robert is smitten with Mabel, his stunning bride, but he gradually becomes aware that, from her perspective, something in the marriage is amiss. Desperate to find out what it is, he asks his friend, who has been flirting with Mabel’s maid, to see what he can find out. His friend reveals that, during the train ride down, the porter threw away Mabel’s copy of Vanity Fair. Really, Vanity Fair? That’s what I get after all those ads? An advertorial?

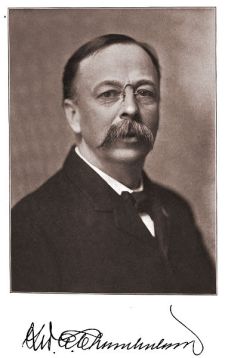

Most famous thinker no one cares about today: G.K. Chesterton

G.K. Chesterton, date unknown

1918 was a bad year, great thinker-wise. Mark Twain died in 1910. So did William James, followed by his brother Henry in 1916. Walter Lippmann was starting to make his mark, but he was still in his twenties in 1918, and in any case he was on hiatus from journalism, working as an assistant to the Secretary of War. So that leaves…G.K. Chesterton. He’s probably best known today for his Father Brown detective stories, but back then he was known for, well, everything. He was a critic and a historian and a theologian and a bunch of other things. Everyone was always quoting him or criticizing him or reviewing his books. There could be a reading-in-1918 drinking game where you take a shot every time someone mentions him. Luckily there isn’t, because I’d be sozzled all the time.

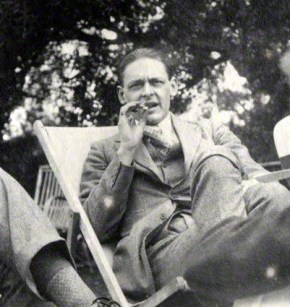

Least famous thinker everyone cares about today: T.S. Eliot

T.S. Eliot, 1923 (Lady Ottoline Morrell)

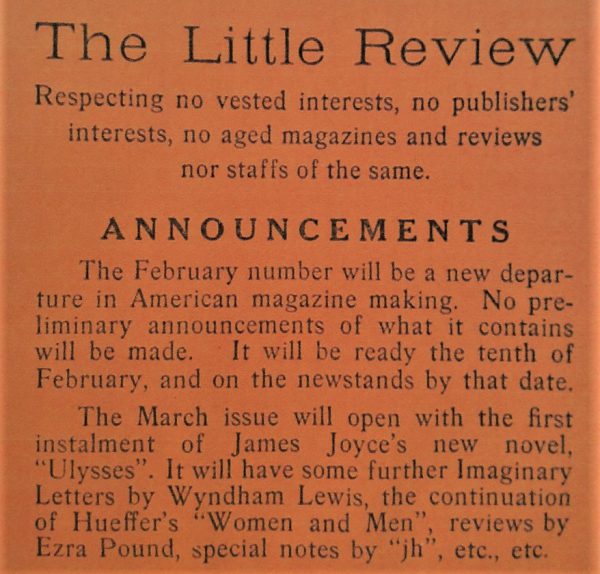

Okay, Eliot, who was 30 in 1918, wasn’t completely unknown. “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” had been published in Poetry magazine in 1915, and The Egoist, where he was assistant editor, put together a small collection of his poems in 1917. He was publishing reviews in The Egoist and elsewhere. But he was still working as a banker, and no one, except maybe Ezra Pound, suspected that he’d end up as the century’s most important poet and critic.

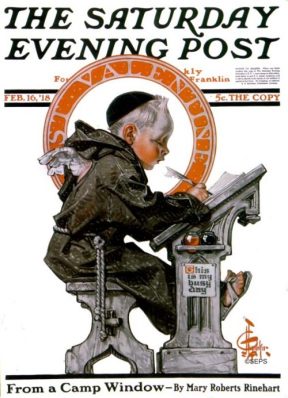

Best joke:

Geraldine—Why didn’t you enlist?

Gerald—I had trouble with my feet.

Geraldine—Flat, or cold?

(Judge, January 5, 1918)

Judge magazine, January 5, 1918

I know what you’re thinking: “This joke is not funny at all. I wish I could go back in time and never have heard this joke.” But, believe me, this is the best joke I could find. I know. It’s sad.

Worst joke:

It’s pretty much a tie between all the other jokes I read this month. They’re either corny, like this one:

“I’d like to have Simpkins’ yellow streak.”

“Why you coward!”

“It’s in a gold mine.”

or incomprehensible, like this one:

He—What music are you going to have at your dance?

Other he—The fraternity hat-band.

(Both from Judge, January 5, 1918)

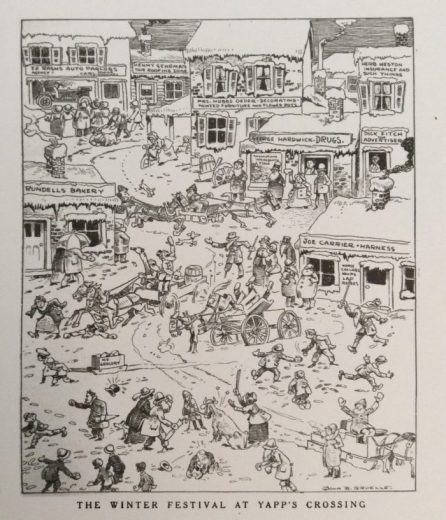

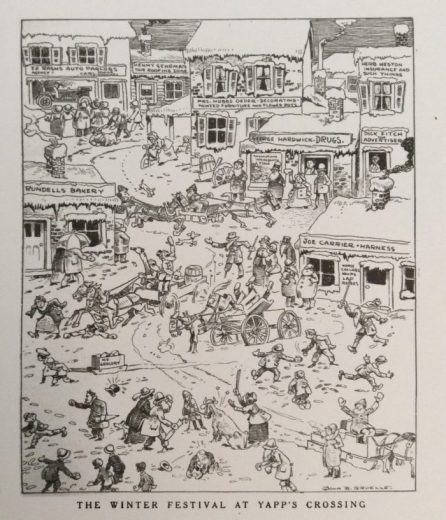

Okay, I can’t end on that note. As I’ve noted before, Judge did have excellent illustrators. I’ll close out the month with another Yapp’s Crossing illustration from John Gruelle, who, it turns out, was the creator of Raggedy Ann and Raggedy Andy.

On to February!