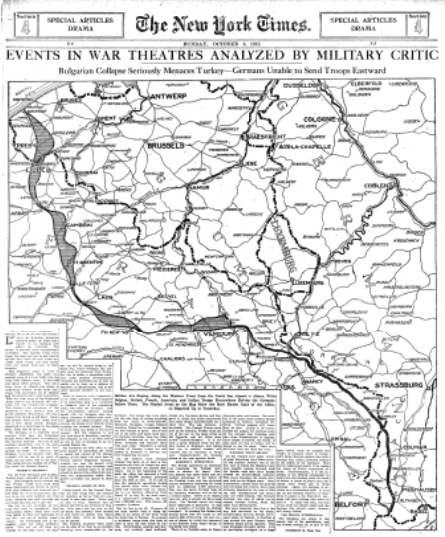

Just two days to go in My Year in 1918! After spending 2018 reading books, magazines, and the news as if I were living a century ago, I’m excited but also nervous about returning to the modern world.

Before that, though, I thought I’d count down the most popular posts of the year.

The Top 10 (well, really 11 because there’s a tie at #10)

10 (tie). Dear Daddy-Long-Legs, Drop dead! In this February post, I reread the Jean Webster classic, in which an orphan writes to the benefactor who’s putting her through college. An aspect of the story that seemed charming to 12-year-old me struck me as creepy this time around. (No spoilers here, but I spoil away in the post itself.)

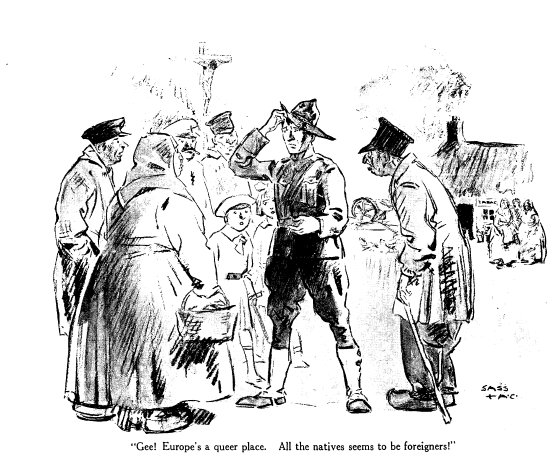

10 (tie). The best and worst of June and July 1918: Insanity, proto-flappers, and octopus eyes. This post, featuring one of my favorite magazine finds of the year, the American Journal of Insanity, the worst New York Times editorial I read all year, which is saying a lot, and Murad cigarette art, probably benefited from sitting at the top of the blog for two weeks while I was in D.C. being lazy.

9. My Year in 1918: Some thoughts at the halfway point. In which I ruminate about life as a literary time traveler, and about how checking out of the 2018 news has affected me.

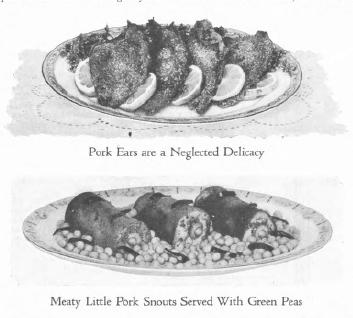

8. Wish me luck on my 1918 diet! Surprise surprise—people like reading about diets. My Year in 1918 had its best week ever with this October post on how I tried to regain the silhouette of youth by going on a 1918 diet, spurred on by a group DietBet.

7. The bonkers world of Marie Corelli. During my very first week, I read a New York Times article about how British novelist Corelli, whom I’d never heard of,* had been arrested for hoarding sugar. A little digging turned up an article in the January 1918 issue of Good Housekeeping in which she rants about modern horrors like Cubism and Debussy and ruminates insanely on who should be shot like a mad dog and who should be involuntarily sterilized—my first, but by no means last, encounter with 1918 eugenic thinking.

6. The journey begins! My January 1 post, in which I announce my project and make several promises I will fail to keep.

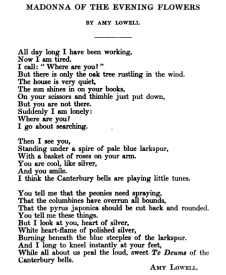

5. The surprisingly ubiquitous lesbians of 1918: A Pride Month salute. One of the biggest surprises of my project was how many lesbian women I came across, either out (The Little Review editor Margaret Anderson), closeted (Willa Cather), or closeted except that it’s totally obvious if you read their poetry so it’s mind-boggling to a modern reader that people didn’t get it (Amy Lowell).

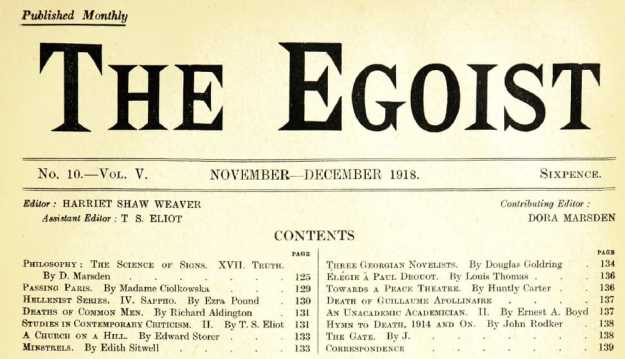

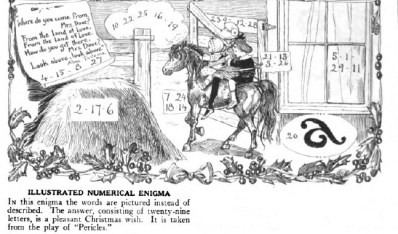

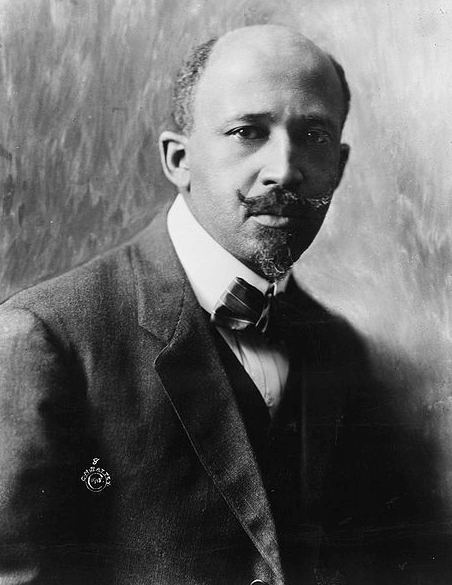

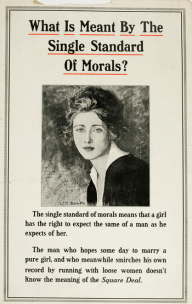

3 (tie). The best and worst of January 1918: Magazines, stories, thinkers, and jokes. The biggest head-scratcher on the list. I mean, I stand by it—it has W.E.B. Du Bois’s wonderful magazine The Crisis, and T.S. Eliot, and a G.K. Chesterton drinking game, and bad jokes—but I’m not sure what propelled it into the tied-for-#3 spot. The internet is a mystery sometimes.

3 (tie). What’s Your 1918 Girl Job? Take This Quiz and Find Out! Don’t count on keeping your “war job” when peace comes, the Ladies’ Home Journal (correctly) warns. Set your sights on a realistic career, like teacher, saleswoman, office girl, or dressmaker. Take this quiz to find YOUR 1918 girl job!

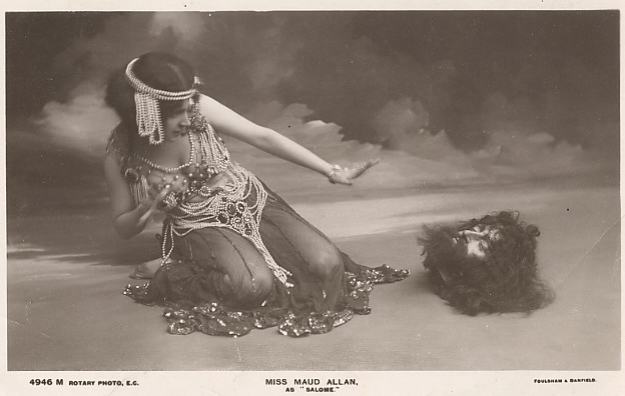

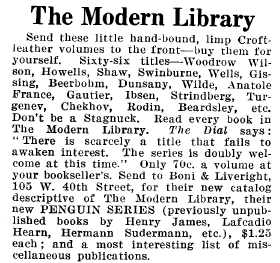

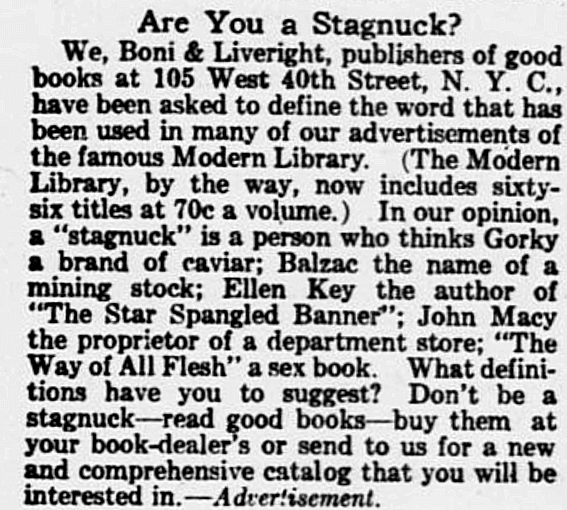

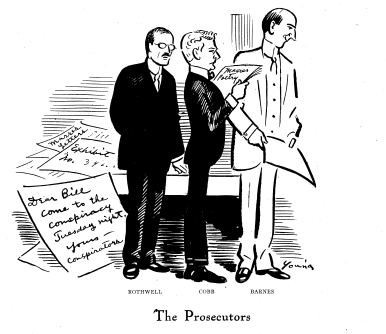

2. Unmentionable vice, a secret German book, and a camarilla: The (looniest) trial of the century. This is the craziest story I came across all year, and that’s saying a lot. It’s about a dance production based on Oscar Wilde’s Salome and a libel trial spurred by an item about it in Member of Parliament Noel Pemberton-Billing’s right-wing newspaper, headlined “The Cult of the Clitoris.” Oh, and there’s (allegedly) a 47,000-member German-lesbian cabal. Except that the New York Times couldn’t say “clitoris” or “lesbian” so I had a terrible time figuring out what was going on.

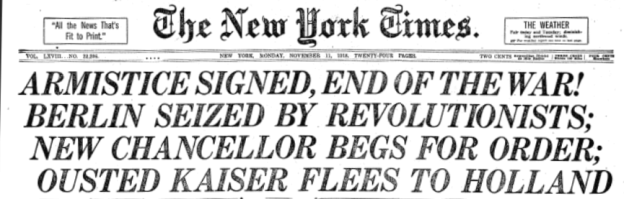

And the winner

1. Are you a superior adult? Take this 1918 intelligence test and find out! This post didn’t do all that well when it was published in February, but its continuing popularity over the year won it the top spot. You, too, can find out whether you’re a superior adult (as opposed to, say, feeble-minded or deficient) by taking this 100-word vocabulary test from Literary Digest. Which is totally accurate, the magazine assures us, because being able to identify a cameo or a parterre or shagreen has NOTHING to do with your socioeconomic status.

Honorable Mentions

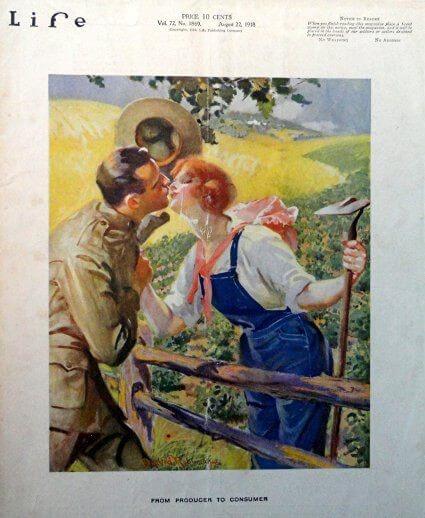

My Sad Search for 1918 Love. This post, in which I search in vain for a nice 1918 boyfriend, came in 13th despite having been published in mid-December.

Illustration by Adelaide Hanscom Leeson, “The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam,” 1905, with George Sterling as model

The Uncrowned King of Bohemia: The fascinating story of a not-so-great poet. Almost as crazy as the Unmentionable Vice story, this tale of a bad poet, scandalous goings-on in Carmel-by-the-Sea, and much taking of cyanide performed spectacularly when first posted, but then faded and didn’t even make the top 20.

Dishonorable Mention

Thursday Miscellany: Mauvais français, trippy Kewpies, and loud loos. Don’t you always wonder what people’s worst-performing posts are? I do! My bottom ten were all Miscellanies or very early, kind of earnest, posts. The nadir, with TWO views,** is this one. It’s a pretty typical Miscellany, so I’m not sure why the hate. Although on second thought it IS kind of creepy, with kewpies, which always freak me out, and scary wall faces, and a toilet. You can click on the link if you feel sorry for it.

So What Does it All Mean?

Some takeaways: people like reading about loony bohemian goings-on and diets and lesbians and bests and worsts and explanations of what people’s blogs are about. And they love quizzes!

Well, all of you quiz lovers are in luck, because there’s one going on right now: a test of your Year-in-1918 knowledge. Enter by 1 a.m. EST on January 4 for a chance to win a book of your choice from the Book List!***

*Which seems inconceivable to steeped-in-1918 December me, since she was hugely famous.

**But you don’t have to feel TOO sorry for it, because numbers of views are kind of misleading. If you look at a post on the home page and don’t click on it, it counts as a view for the home page. So, to make a blogger happy, click on the link.

***For you people who say the quiz is hard—YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE—it’s not! It’s an open-book test, and with judicious use of the search bar a perfect score can easily be yours. One of the answers is right here on this post!

New reviews on the Book List:

December 28: Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery (1908)

December 29: The Answering Voice: One Hundred Love Lyrics by Women, edited by Sara Teasdale (1917)