1918 is a depressing year to look back on: war, influenza, rampant racism and sexism. But when something is depressing in retrospect that means we’ve made progress, right? I don’t mean to sound Pollyannaish about 2018—believe me, I’m not. For Thanksgiving, though, I decided to look at some of the people of 1918 who paved the way for the better world—and, for all its problems, it is a better world—we’re living in today.

So thank you, in no particular order, to

1. Jane Addams and the settlement movement

Jane Addams reads to children at Hull House (Jane Addams Memorial Collection, University of Illinois at Chicago)

Jane Addams is one of my 1918 heroes. I had heard of her as the founder of Hull House, the famous Chicago settlement house, which I vaguely imagined as a social services center for the immigrant community. Then I listened to an audiotape of her wonderful memoir Twenty Years at Hull-House and learned that it was so much more—a playhouse and dance hall and crafts museum and lecture theater and book discussion venue and art gallery and sanitation office and whatever else Addams and her fellow settlement workers thought would uplift immigrants from their miserable living conditions. Some of her ideas worked, others didn’t (she discusses the failures with self-deprecating good humor), but she brought astonishing energy and creativity to her mission. Addams received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931 and is now known as the “mother of social work.”

The rights of immigrants are under threat today, as they were in 1918, but today, at least, there are hundreds of organizations to protect and assist them.

Thank you, Jane Addams!

2. William Carlos Williams and my new favorite poem

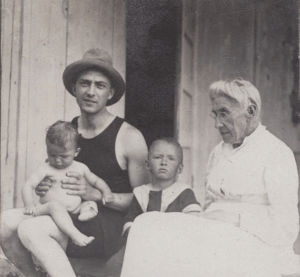

William Carlos Williams with his sons, Paul and William, and his mother, circa 1918 (Beinecke Library, Yale University)

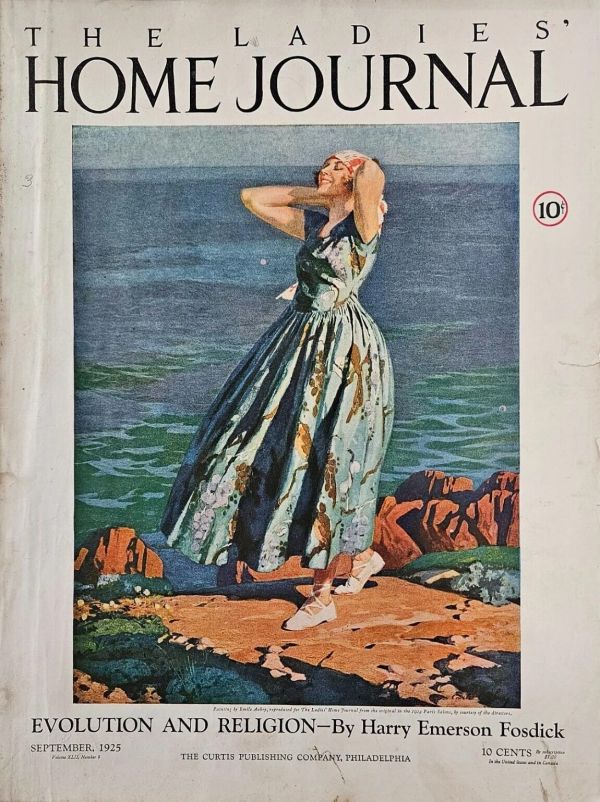

There was a LOT of bad poetry around in 1918. Or not bad, exactly, just sentimental, bland, and innocuous—sitting in the background like wallpaper. Like this poem. (In the unlikely event you want to read the rest, you can do so here.)

Scribner’s, November 1916

Then the modernists came along and changed everything. They threw aside Victorian notions of beauty and upliftment, as well as meter and rhyme, and wrote about the world they actually saw. The poet I’ve come to know best over the year (after a rocky start) is William Carlos Williams. I recently memorized his relatively little-known but wonderful poem “January Morning,” an account of his early-morning amblings on a winter day. Here’s how it begins:

I have discovered that most of

the beauties of travel are due to

the strange hours we keep to see them:

the domes of the Church of

the Paulist Fathers in Weehawken

against a smoky dawn–the heart stirred–

are beautiful as Saint Peters

approached after years of anticipation.

(And yes, I typed that off the top of my head. You can check for mistakes, and read the rest of the poem, here.)

Thank you, William Carlos Williams!

3. W.E.B. Du Bois, the NAACP, and The Crisis

Portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois on the cover of The Crisis, February 1918

W.E.B. Du Bois is up there with Jane Addams in my 1918 pantheon. He gave up a successful academic career to edit The Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine for the African-American community. The Crisis took on discrimination and lynching and other horrors, but it also celebrated the achievements of the community’s “Talented Tenth” (like scholar-athlete Paul Robeson) and printed pictures of cute babies.

Thank you, W.E.B. Du Bois!

4. Harvey Wiley, the FDA, and healthy food

Dr. Wiley in his USDA lab (FDA)

If your turkey dinner isn’t full of dangerous preservatives, you have Harvey Wiley to thank. From his lab at the USDA, Wiley pioneered food safety by testing chemicals on a group of young volunteers known as the “Poison Squad.” While his methods wouldn’t get past the ethics committee today, his efforts on behalf of passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act earned him the nickname “Father of the FDA.”

Thank you, Harvey Wiley!

5. Anna Kelton Wiley and women’s suffrage

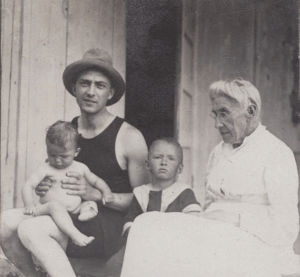

Anna Kelton Wiley with her sons

Anna who? you may be asking. Anna Kelton Wiley wasn’t America’s most famous suffragist. That would be Alice Paul. Paul deserves our thanks as well, but I thought of Wiley—Harvey Wiley’s much younger wife—because it’s not just the leaders who matter, it’s all the people in the rank and file who fight locally, day by day, for a better world. Women’s suffrage wasn’t a single victory, won in 1920, but a battle fought and won, state by state, over many years. Now more than ever, this is a lesson we need to remember.

Wiley wrote in Good Housekeeping that she and other suffragists decided to picket the White House—a highly controversial move—after less confrontational methods had failed. The demonstrations, she said, were

a silent, daily reminder of the insistence of our claims…We determined not to be put aside like children…Not to have been willing to endure the gloom of prison would have made moral slackers of all. We should have stood self-convicted cowards.

Thank you, Anna Kelton Wiley!

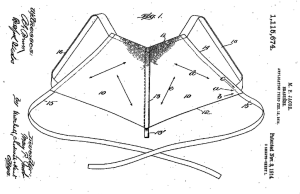

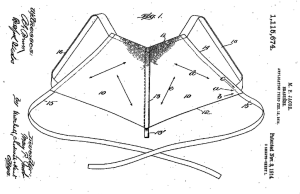

6. Mary Phelps Jacob and comfortable underwear

Mary Phelps Jacob, ca. 1925 (phelpsfamilyhistory.com)

Segueing from women’s suffrage to underwear might seem like going from the sublime to the ridiculous, but it’s all part of the same thing. Disenfranchisement was one way to keep women down; corsets were another. Corsets were still very much around in 1918, but they were on their way out, partly due to wartime metal conservation efforts. And bras were on their way in, thanks to Mary Phelps Jacob, a socialite who, putting on an evening gown one night in 1913, found that the whalebone from her corset was sticking out from the neckline. With the help of her maid, she improvised a garment out of two handkerchiefs and a piece of ribbon. She patented it the next year as the “Backless Brassiere,” and the rest is history.

Brassiere patent drawing, Mary Phelps Jacob, 1914

Thank you, Mary Phelps Jacob!

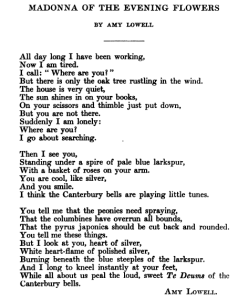

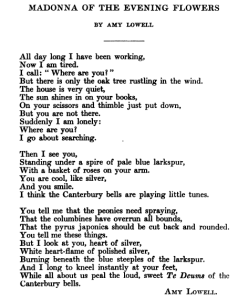

7. Amy Lowell and LGBT pride

Amy Lowell, ca. 1916

Amy Lowell wrote about love as she experienced it—with her partner, Ada Dwyer Russell, in the Boston home they shared. They weren’t able to live openly as lovers, and Dwyer destroyed their correspondence at Lowell’s request, but their love shines through in Lowell’s poems. Here’s one of my favorites:

North American Review, February 1918

Thank you, Amy Lowell!

8. Katharine Bement Davis and sexual freedom

Katharine Bement Davis, 1915 (Bain News Service)

We think of sexual freedom as the right to sleep with whoever we want, inside or outside marriage. It is that, of course, but it also involves rights that we take so much for granted today that we don’t even think about them. Like the right of a wife who has contracted a sexually transmitted disease from her husband not to be lied to by her doctor. The right of a young woman to know the facts of life rather than being kept in ignorance to uphold an ideal of “purity.” The right of a teenager not to live in fear that masturbation will lead to blindness and insanity. The right of a couple to practice birth control without risking prison.

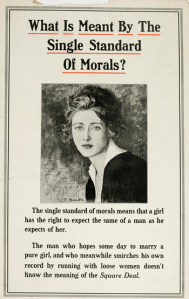

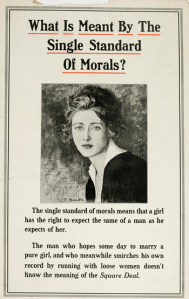

Poster, War Department Commission on Training Camp Activities, ca. 1918

Katharine Bement Davis, a settlement worker and social reformer, was at the forefront of the fight against sexual ignorance. When the United States entered World War I, venereal disease turned out to be rampant among recruits. Davis wrote in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science that combating this epidemic required efforts—and knowledge—on the part of “both halves of the community which is concerned.” Davis and her team at the Section on Women’s Work of the Sexual Hygiene Division of the Commission on Training Camp Activities educated women on sexual issues with publications, films, and lectures by women physicians.

Okay, Davis’s solution was that no one, male or female, should have sex outside of marriage. And she, like so many progressives, was a eugenicist. Still, breaking down the walls of ignorance was an important step.

Thank you, Katharine Bement Davis!

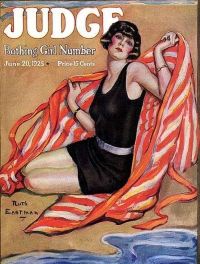

9. Dorothy Parker and humor that’s actually funny

Dorothy Parker, date unknown

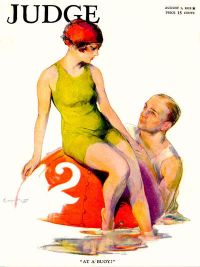

1918 humor was, for the most part, not funny. There were racist and sexist jokes, faux-folksy tales, and labored puns. Here is a joke I picked at random from Judge magazine:

Judge, November 9, 1918

Then Dorothy Parker came along, filling in for P.G. Wodehouse as Vanity Fair’s drama critic, and changed everything. The best way to make a case for Dorothy Parker is to quote her, so here are some excerpts from her theater reviews:

On the musical Going Up, April 1918: It’s one of those exuberant things—the chorus constantly bursts on, singing violently and dashing through maneuvers, and everybody rushes about a great deal, and slaps people on the back, and bets people thousands of stage dollars, and grasps people fervently by the hand, loudly shouting, “It’s a go!”

On the farce Toot-Toot!, May 1918: I didn’t have much of an evening at “Toot-Toot!” I was disappointed, too, because the advertisements all spoke so highly of it. It’s another of those renovated farces—it used to be “Excuse Me,” in the good old days before the war. I wish they hadn’t gone and called it “Toot-Toot!” When anybody asks you what you are going to see tonight and you have to reply “Toot-Toot!” it does sound so irrelevant.

Thank you, Dorothy Parker!

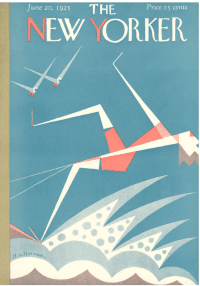

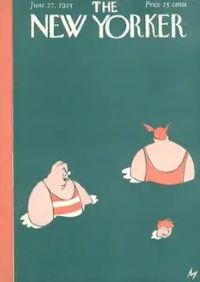

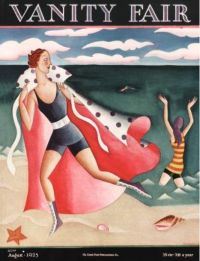

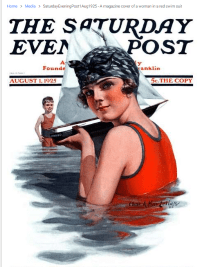

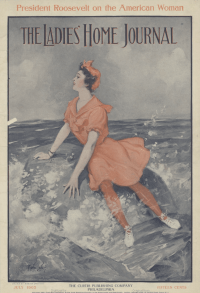

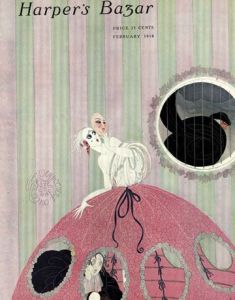

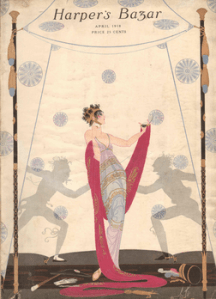

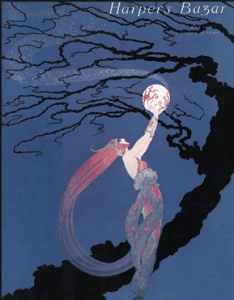

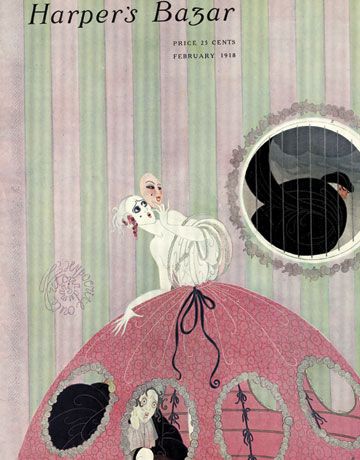

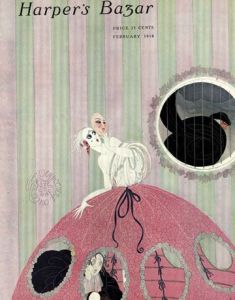

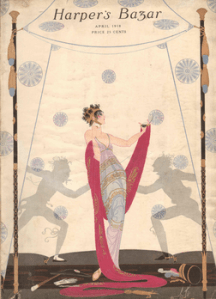

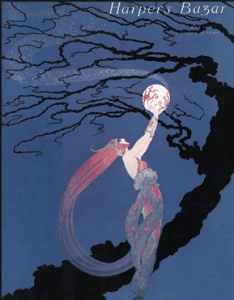

10. Erté and gorgeous magazine covers

Roman Petrovich Tyrtov (Erté), date unknown

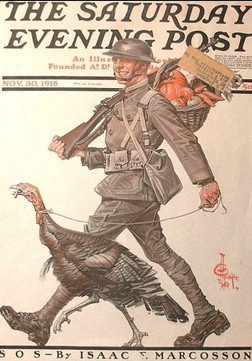

Okay, this doesn’t fit into my theme, because 1918 was the golden age of magazine covers and I get depressed whenever I pass by a 2018 magazine rack. But the beautiful cover art of the era is worth celebrating anyway. There were many wonderful artists, but the master was Erté, who turned twenty-six on November 23, 1918.

Thank you (and happy birthday), Erté!

The common thread on this list, I see, is freedom. Freedom for women, immigrants, people of color, and the LGBT community, but also less obvious but still important types of freedom: to wear clothes you can move around in, to know the facts of life, to eat healthy food, and to write about and laugh about the world as it really is.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone! And thanks to all of you out there who, in large ways and small, are working to make the world of a hundred years from now better than the one we live in today.