After almost a year in 1918, I have yet to find a decent man.

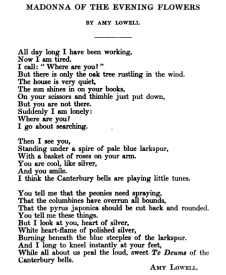

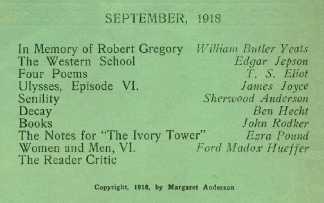

If I were gay, I’d have it made—this was the golden age of (if not for) lesbian women. Amy Lowell! Willa Cather! Little Review editor Margaret Anderson! Dancer Maud Allan! Plus lots of probablys like Jane Addams and Edna Ferber. But no, I’m stuck with men.

Back in January, I checked out two prospects*, H.L. Mencken and Walter Lippmann. Mencken’s denunciation of American Puritanism and hypocrisy appealed to me, but then he started going on about Jews and using racial slurs and I was over him. Lippmann seemed stodgy at first, but he won me over by sneaking a bunch of double-entendres into a sober discussion on prostitution in his 1912 book A Preface to Politics.

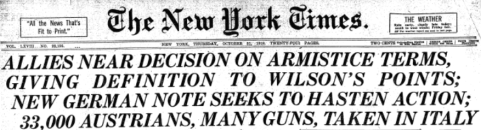

But then he disappeared, as seemingly good men often do. Having left the New Republic to head up the War Department’s propaganda office in Paris, he was almost invisible in 1918. The only traces of him I could find (aside from a swipe from Mencken about his “sonorous rhapsodies”) were two New York Times articles from right before the armistice about an operation he was running to drop leaflets over Germany.

So my search continued. After ruling out men who

- died before the end of 1918 (RIP war poet Francis Hogan, essayist Randolph Bourne, and college-will-shrink-your-breasts doctor Henry Maudsley, not that he would have had a chance),

- were gay (Erté),

- committed suicide (Uncrowned King of Bohemia George Sterling) or ended up in an insane asylum (Ezra Pound and cartoonist Percy Crosby),

- espoused right-wing political causes (Columbia University president Nicholas Butler, British MP Noel Pemberton-Billing, and Senator James Vardaman, among others), or

- seemed like okay guys but I didn’t get to know them all that well (short story anthologist Edward O’Brien, writer Harold Kellock, historian Charles Beard, poet/critic Conrad Aiken**, critics Carl van Vechten and Van Wyck Brooks (who I always get mixed up), painter William Edouard Scott, and Dere Mable author Edward Streeter). (UPDATE 10/18/2020: It turns out that Van Vechten had a number of same-sex relationships over the course of his fifty-year marriage to a Russian-born actress.)

I was left with ten men worth a closer look.

T.S. Eliot

T.S. Eliot was my first 1918 love, way back in the eighties, when the internet wasn’t invented so people had to entertain themselves by memorizing The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Or maybe that was just me. You can disturb MY universe any time, T.S., I would say to myself. Even then, though, there were warning signs. Like how in the very next poem he’s hanging out with an older woman and wondering if he would have a right to smile if she died. But what can I say? I was twenty-two.

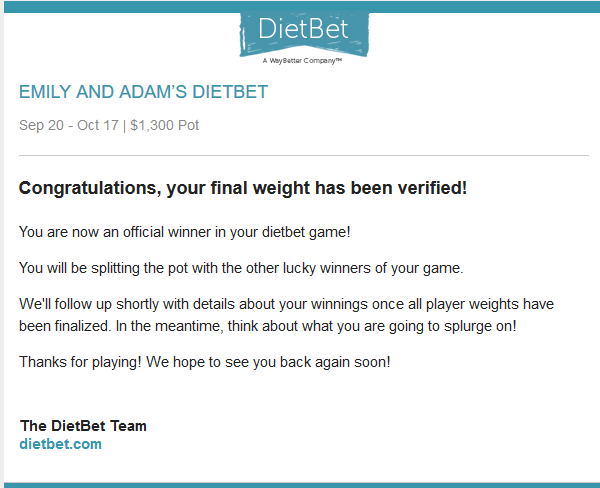

As I read more Eliot, and learned more about him, disillusionment set in. For a lot of reasons, but the anti-semitism alone would have been enough. It’s evident already in 1918, in the poem “Sweeney Among the Nightingales,” published in the September 1918 issue of The Little Review.***

Good-bye, T.S.!

George Jean Nathan

If Mencken wasn’t the guy for me, what about George Jean Nathan, his best pal and Smart Set co-editor, who was also the preeminent drama critic of his time? Smart and funny and urbane, and an excellent source of theater tickets.

Digging around to find out whether he shared Mencken’s anti-semitism, I learned that he was part Jewish himself—and that he went to great lengths to hide this. Which would be a deal-breaker today, but those were different times. Case in point: movie star Lilian Gish, whom Nathan was madly in love with, supposedly broke up with him when she learned of his Jewish roots.

But have you seen All About Eve? If so, do you remember the poisonous middle-aged critic who was squiring around 24-year-old Marilyn Monroe? Turns out he was based on Nathan.

Good-bye, George!

Alan Dale

More than anything else I’ve written about this year, the story of Alan Dale’s play The Madonna of the Future has stuck with me. A Broadway play about a society woman who becomes a single mother by choice and acts like it’s no big deal? In 1918? How could this be? (Well, it wasn’t for long—facing obscenity complaints, the play closed after a month or so.) I was intrigued. Who was this Alan Dale person?

The hackiest of Broadway hacks, as it turns out. According to Nathan, the British-born Hearst drama critic (real name Alfred Cohen) perpetrated

the sort of humor…whose stock company has been made up largely of bad puns, the spelling of girl as “gell,” the surrounding of every fourth word with quotation marks, such bits as “legs—er, oh I beg your pahdon—I should say ‘limbs’,” a frequent allusion to prunes and to pinochle, and an employment of such terms as “scrumptious” and “bong-tong.”

I couldn’t be with someone who said “bong-tong.” Plus, might the author of the first gay-themed novel in the English language, which Dale also was, possibly be gay?****

Good-bye, Alan!

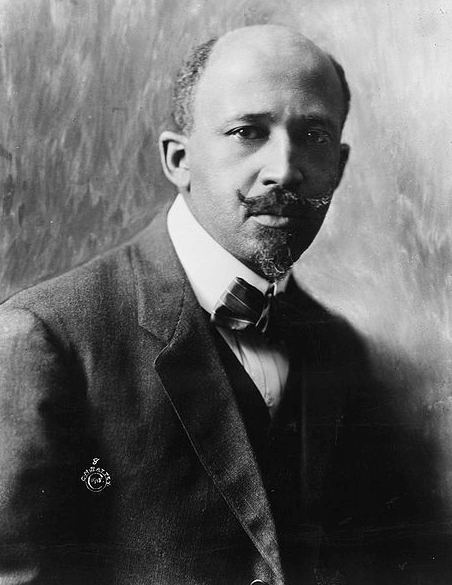

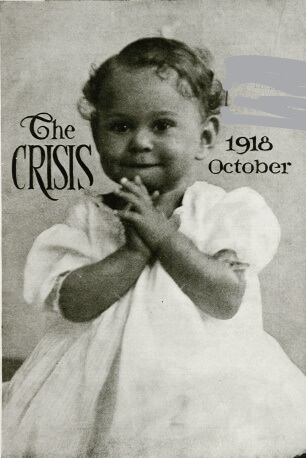

W.E.B. Du Bois

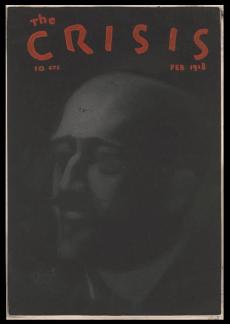

Du Bois was a brilliant thinker and a wonderful writer and his magazine The Crisis is one of my favorite discoveries of 1918. But, the world being what it was in 1918, this wasn’t going to happen.

Plus, he intimidates the hell out of me.

Good-bye, W.E.B.!

H.G. Wells

Wells was the alpha male of the British literary scene, regarded as one of the greatest writers and thinkers of his day. It would no doubt astonish a 1918 person to learn that he would be known in the future primarily as a science fiction writer.

As a romantic partner, though? Bad news! Married to his cousin, he was always sleeping with other women, including a Soviet spy and birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger. Who at least could be relied on not to get pregnant, unlike 26-year-old writer Rebecca West and the daughter of one of his Fabian friends, both of whom bore him children.*****

Good-bye, H.G.!

James Hall

James Hall lied and said he was Canadian to get into World War I, was caught and got kicked out, joined the American branch of the French air force, and was shot down just after he was finally able to fly under American colors. He was feared dead but turned out to have been captured by the Germans. After the war, he moved to Polynesia and co-wrote, among other books, Mutiny on the Bounty.

A cool guy, but I’m not into the swashbuckling type.

Good-bye, Jimmy!

Christopher Morley

A prolific young literary man-about-town, Morley published the popular novel Parnassus on Wheels and a book of poetry called Songs for a Little House in 1917 and an essay collection in 1918. He was also the literary editor of Ladies’ Home Journal. He married young, stayed married, and never got up to any shenanigans that I know of.

On the other hand, this is how he wrote about his wife:

I would die.

Good-bye, Christopher!

Harvey Wiley

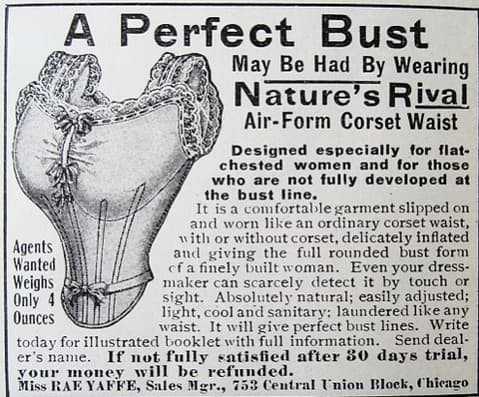

Harvey Wiley fought against toxic preservatives in foods and was a driving force in the creation of the FDA. He’s one of my 1918 heroes.

Most of the badmouthing I’ve read about Wiley has broken down on examination. It’s been said that he thought women were stupid, but I haven’t found any evidence.****** He’s been called a eugenicist, but the main case for the prosecution is him saying in Good Housekeeping that there’s no better genetic stock than Scots-Irish, which I think was just him being funny because that’s his background. (This is, in any case, pretty mild as eugenics goes.) I’ll have to wait until 2019 rolls around and I can read his new biography to get the lowdown.

In the meantime, though, there’s this: if you’re the kind of guy who, at age 55, is so taken with your 22-year-old secretary that after she leaves you carry her picture around in your watch for ten years until you run into her on a streetcar and marry her, you’re probably not the guy for me.

Good-bye, Harvey!

Louis Untermeyer

Untermeyer is one of those 1918 people I remember from when I was growing up, the editor of pretty much every literary anthology I came across. In 1918, he was all over the place, writing criticism for The Dial and The New Republic and poetry for The Smart Set and many other publications. He’s like a non-smarmy Christopher Morley. His wife, Jean Starr Untermeyer, was also a poet. I thought I might have found my man.

Then I looked into his life. He and Jean divorced in 1926, then he married someone else, then he and Jean got married again in 1929 but divorced in 1930. Then he married a judge named Esther Antin, and they lasted for over a decade, but then he got a Mexican divorce. She was presumably the wife who said in a lawsuit that he was, at 63, “still an inveterate anthologist, collecting wives with an eye always open for new editions.” His last marriage was to a much younger Seventeen magazine editor who wrote a book about their cat.

Good-bye, Louis!

William Carlos Williams

And now for the one who broke my heart.

William Carlos Williams seemed like the ideal man. A groundbreaking poet AND a successful pediatrician. From New Jersey, like me. Part Puerto Rican, so I could practice my Spanish!

We even had a meet-cute story: In an early post, I trashed his foray into Cubist poetry. Kind of like H.G. Wells and Rebecca West, who met after she panned a book of his, except without the part where she immediately gets pregnant and they don’t admit to their son for quite a while that they’re his parents.

It was the 1917 collection Al Que Quiere! that made me fall in love. In “Danse Russe,” he dances around naked in his study, admiring his butt in the mirror, as his wife and nanny and children are napping. In “January Morning,” a poem I love so much I memorized all 500+ words of it, he takes us around Weehawken, New Jersey and environs, dancing with happiness on a rickety ferry-boat called Arden.

Here’s how the poem ends:

Well, you know how the young girls run giggling

on Park Avenue after dark

when they ought to be home in bed?

Well, that’s the way it is with me somehow.

A cheerful modernist, what a concept!

And there’s more. Judging from “Dedication for a Plot of Ground,” his tribute to his fierce, difficult grandmother, he appreciated strong women. He was attractive in a non-threatening way.******* Politically progressive without being loony. And a great family man! He married his wife Flossie in 1912 and they stayed married, stolen plums and all, until his death in 1963. Aside from the minor issue of how you could be named William Williams and then name your son William, he seemed perfect.

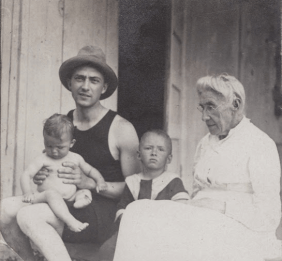

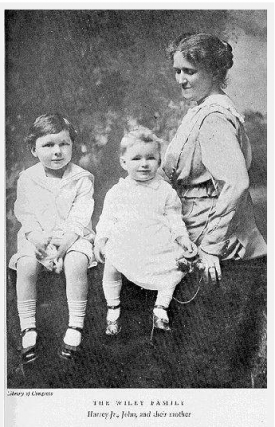

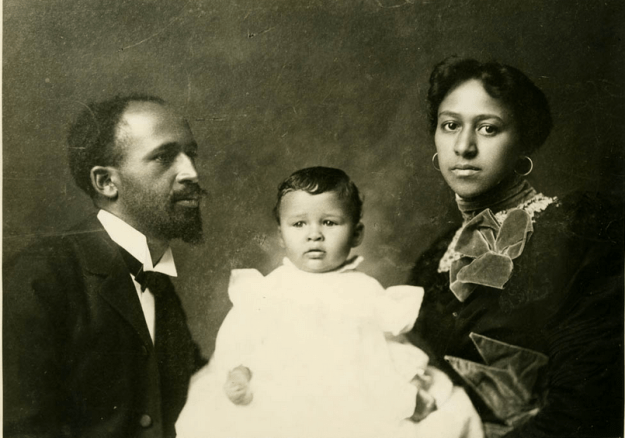

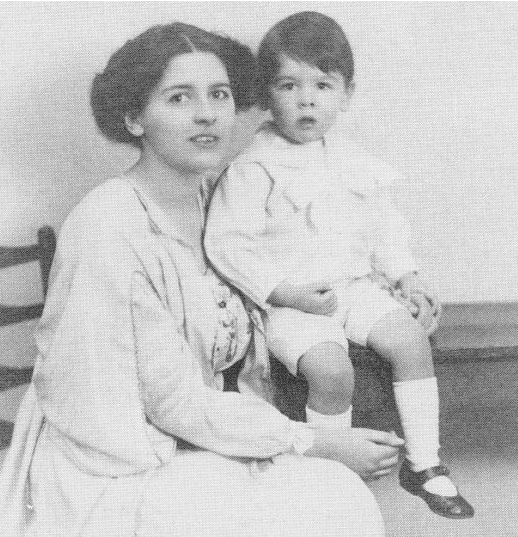

William Carlos Williams with his sons, Paul and William, and his mother, Raquel Helene Rose Hoheb Williams, ca. 1918

The first warning sign came at the end of Al Que Quiere!: a reference to “lewd Jews’ eyes” in the long poem “The Wanderer.” An isolated incident, I hoped. But, when I looked further, it all started to fall apart. The final blow came in a Washington Post review of a 1981 biography of Williams. The biographer acknowledges that he threw around an anti-Jewish ethnic slur but says that this wasn’t antisemitism, it was just part of the “popular racial myths of his time.” The reviewer responds, “Exactly. ‘Popular racial myths’ are what racism consists of.”

Exactly.

Good-bye, W.C.!

At this point I threw up my hands and said,

Which, if you don’t know French (and yes, Ezra Pound, there are such people), means “I don’t even want to know if there were men before me.”

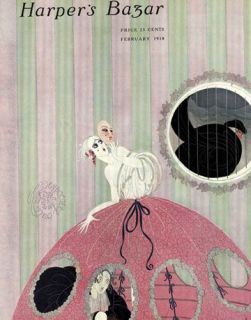

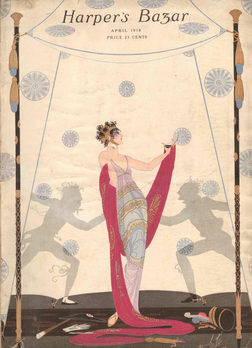

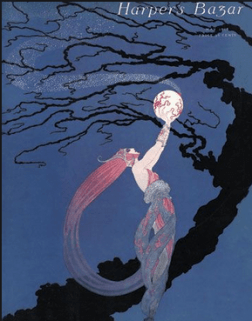

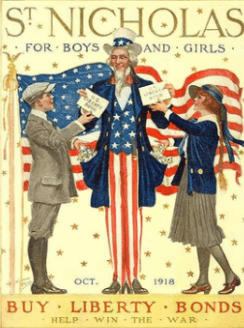

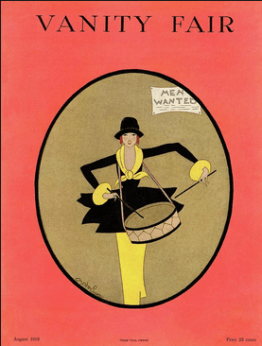

There are lots of ways 1918 was better than 2018. Cars looked cooler

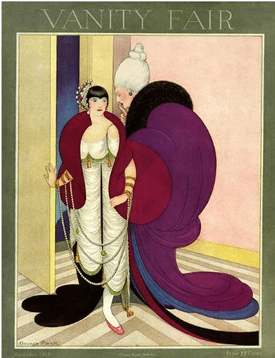

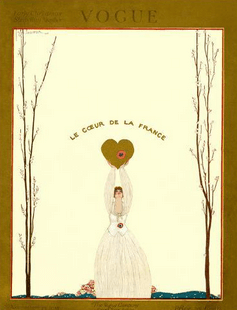

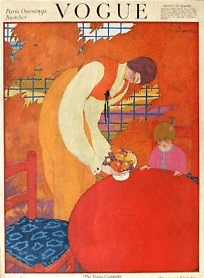

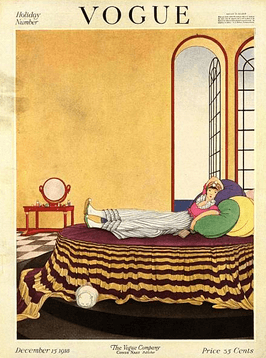

and magazine covers were more attractive

George Wolfe Plank, Vogue, December 15, 1918

and, regardless of whether you’d want to marry them, these men were part of a far greater literary age than our own.

But my search for 1918 love has made me grateful that I’m living in a world of 2018 men.

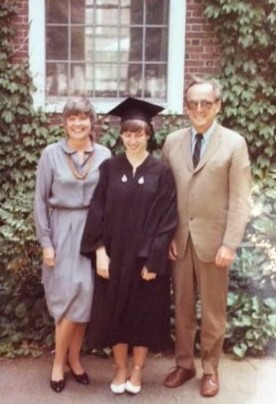

Especially the one I married 15 years ago today.

Happy anniversary, S.!

*I’m not being fussy here about whether people were single in 1918 (Mencken was; Lippmann wasn’t), or whether they were age-appropriate for a 100-years-older me.

**Who I just now found out was the father of Joan Aiken, one of my favorite children’s authors (The Wolves of Willoughby Chase, etc.).

***Also, Virginia Woolf called Eliot’s first wife a bag of ferrets around his neck in her journal, and I’d hate it if she said that about me.

****Judging from the photo, he had a daughter, but that didn’t mean much in 1918.

*****He also slept with the daughter of another Fabian friend, and when fellow Fabian Beatrice Webb called this a “sordid intrigue” he lampooned her and her husband Sidney in a novel.

******He did think some women were stupid, but that’s because they were.

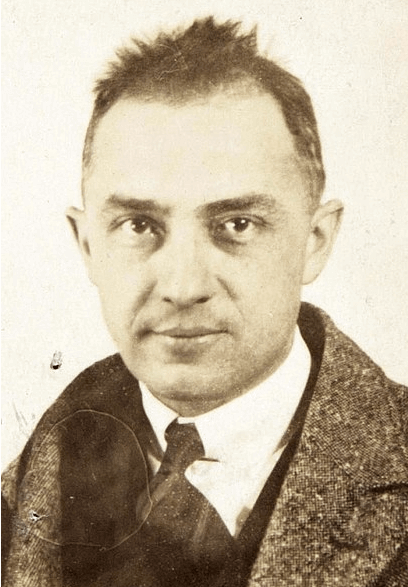

*******If you beg to differ, that’s his passport photo. I got mine taken this week, and even though I made them retake it six times it still looks like the picture of Dorian Gray.