“There is a vendetta between the generations.”

So said critic Van Wyck Brooks in The Dial on April 11, 1918. (UPDATE 12/22/2020: Reading this again, I see that the actual quote is “There is a vendetta between the two generations.”) Randolph Bourne, a colleague of Brooks’ at the magazine, addressed the same theme in his March 28 essay “Traps for the Unwary,” asking

What place is there to be for the younger American writers who have broken the “genteel” tradition?…Read Mr. Brownell on standards and see with what a bewildered contempt one of the most vigorous and gentlemanly survivals from the genteel tradition regards the efforts of the would-be literary artists of today.*

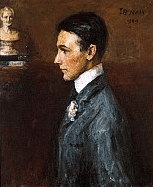

So I read Mr. Brownell on standards. (William Crary Brownell, that is. 1918 writers have an irritating habit of referring to people on first introduction as Mr. or Mrs. or Miss Last Name.) He was, it seems, a founding figure in American literary criticism, having sought to raise the country’s level of criticism as Matthew Arnold had in Britain. H.L. Mencken called Brownell “The Aristotle of Amherst”—not one of his better sallies, IMHO.

Brownell’s thesis in a nutshell: standards are important, but the younger generation doesn’t have them. He singles out “a recent clever novel—by a lady—that has evoked a very general chorus of cordial appreciation.” After quoting from a passage about a guy clipping his toenails, without providing the name of the book or author (another annoying 1918 habit), he says that

the picture is manifestly less a gem of genre than a defiance of decorum…One must draw the line somewhere and it is decorous to draw it on the hither side of the purlieus of pornography.

The lady writer, it turns out, is Virginia Woolf, and the book is her first novel, The Voyage Out.

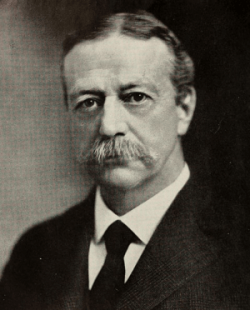

Brownell’s pretty boring, to be honest. Columbia professor Brander Matthews is a more entertaining old fogey. In his essay “The Tocsin of Revolt”,** in the March 1918 issue of The Art World, he says that

when a man finds himself at last slowly climbing the slopes that lead to the lonely peak of three-score-and-ten he is likely to discover that his views and his aspirations are not in accord with those held by men still living leisurely in the foothills of youth…If he is wise, he warns himself against the danger of becoming a mere praiser of past times; and if he is very wise he makes every effort to understand and to appreciate the present and not to dread the future.

The young and old have clashed since time immemorial, Matthews says—and the survival of art depends on these very battles. This is all very sensible, and I wondered what Matthews was doing in such a reactionary magazine.

But!

But at the present moment, and perhaps more especially in our own country, there are signs of danger.

Uh-oh! Like what?

In this new century we have been called upon to admire painting by men who have never learned how to paint, dancing by women who have never learned how to dance, verse by persons of both sexes who have never acquired the elements of versification.

Matthews ends on a hopeful note. Ultimately, he believes, the younger generation

will tire of facile eccentricity and of lazy freakishness, of unprofitable sensationalism and undisciplined individualism. They will again seek the aid of tradition and they will toil to master the secrets of technic.***.

Bourne, a Columbia graduate himself, says of Matthews in a March 14 review of his autobiography that he was “incorrigibly anecdotal, genial, and curious.” He marvels, though, at his portrait of Columbia, then being torn apart by a free-speech controversy, as a paradise of harmoniousness. Ultimately, he delivers a damning verdict:

If there was ever a man of letters whose mind moved submerged far below the significant literary currents of the time, that is the man revealed in this book.

Of Brownell, Bourne says in “Traps for the Unwary” that

one can admire the intellectual acuteness and sound moral sense…and yet feel how quaintly irrelevant for our purposes is an idea of the good, the true, and the beautiful.

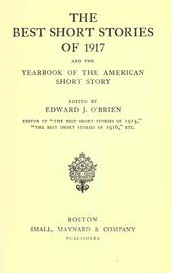

Bourne agrees with Brownell and Matthews that standards are important, and that young people are turning out a lot of junk. The problem, he says, is that the older critics lump all young people together. What’s needed is a new criticism, focused on the younger generation, that

shall be both severe and encouraging. It will be obtained when the artist himself has turned critic and set to work to discover and interpret in others the motives and values and efforts he feels in himself.

In the natural order of things, Bourne could have been a standard-bearer for this new criticism after Brownell and Matthews passed on. But the two elders would survive for another decade, while Bourne had only months to live. Having battled disability and chronic illness throughout his life, he succumbed to influenza on December 22, 1918.****

If Bourne didn’t have the chance to build this new criticism, though, others did—first and foremost T.S. Eliot, who, across the Atlantic, was perfecting his craft as both a poet and a critic.

*The young generation was, I should note, fairly long in the tooth. Brooks was 32 and Bourne was 31. Other members of this literary youthquake included Ezra Pound (32), Margaret Anderson (31), T.S. Eliot (29), and John Reed (30). Meanwhile, much of the actual younger generation—21-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald and 18-year-old Ernest Hemingway, for example—was off fighting in France. (UPDATE 11/17/1918: Actually, neither of them was fighting in France. Fitzgerald a lieutenant in the army but the war ended before he was sent overseas. Hemingway was an ambulance driver in Italy.)

**I think he means toxin. Matthews was an advocate of simplified spelling, so that may be the issue, although I never thought of “toxin” as particularly complicated. (UPDATE 12/16/1918: I came across “tocsin” in the New York Times and it turns out to mean a warning bell. Some dictionaries now consider it archaic.)

***Or technique, as we old-fashioned spellers call it.

****You can learn more about this brilliant thinker, and also about Walter Lippman, Alice Paul, John Reed, and Max Eastman, in Young Radicals, a wonderful book by Jeremy McCarter, co-author of Hamilton: The Revolution.