I grew up with the New Yorker. My family had a subscription. We had a huge cartoon collection that I browsed through constantly. My high school English teacher explained the proper way to read the magazine: front to back, skipping the cartoons and ads, then back to front, reading them. I read books like James Thurber’s memoir The Years With Ross (Harold Ross was the magazine’s founding editor) and Brandon Gill’s Here at the New Yorker. I knew from all this reading that the magazine’s early issues were considered unfunny and sophomoric. So I approached the first issue, dated February 22, 1925, with low expectations.

Which were mostly, but not entirely, met.

Here are some bests and worsts from the 36-page issue. Actually, worsts and bests, because with the way everything else is going these days I’m in the mood to end on an upbeat note.

Worst Archetype

An editor’s note in the debut issue says that the New Yorker “is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque.” This now-famous bon mot also appeared in the magazine’s prospectus and, according to an article about the magazine in the March 2, 1925, issue of Time, “on cards which they tacked up about town.”*

Time claimed to have asked an old lady from Dubuque for her views on the New Yorker’s first issue. The old lady, who was actually Time (and, later, New Yorker) writer Niven Busch, replied, “I, and my associates here, have never subscribed to the view that bad taste is any the less offensive because it is metropolitan taste…there is no provincialism so blatant as that of the metropolitan who lacks urbanity.”

In 1964, Dubuque, playing the long game, sent an actual old lady,** Mary Hayford, to New York to counter the hayseed image. “We have three fine colleges and everyone is studying for their master’s and Ph.D., so we’re very culturally minded,” she told the New York Times. Hayford appeared on the Tonight Show and went on to travel around the country as an ambassador for Dubuque. In her 1989 obituary, the New York Times said that Hayford “helped turn a New York snub into a symbol of pride.”

Best Archetype

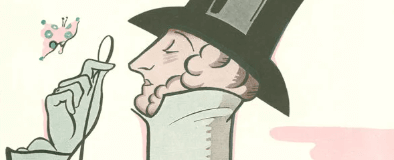

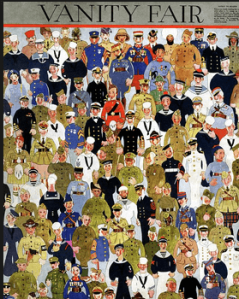

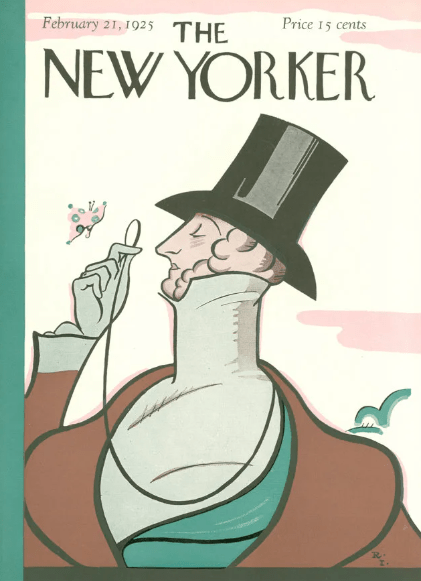

Eustace Tilley,*** Rea Irvin’s cover fop, appears on the magazine’s anniversary covers to this day, sometimes in his original guise, sometimes with a twist. The hundredth-anniversary edition came in six different versions.

Worst Front of the Book Item

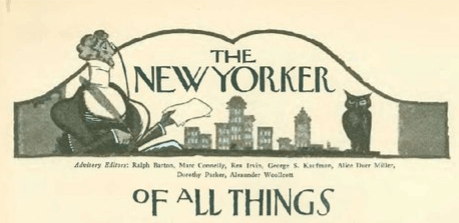

I’m not going to dignify it by reproducing it here, but there’s an item in the “Of All Things” department that manages, in just six lines, to be racist toward both American Indians and Jewish people. The rest of the section mostly consists of jokes about drama critic George Jean Nathan’s love life.****

Best Front of the Book Item

I’m obsessed with 1920s crossword puzzle books,***** so I was interested to read that, according to an anonymous writer in the Talk of the Town section, they’re falling out of fashion in the trendy New York circles where they first became popular. Simon & Schuster, isn’t worried, though; they’re publishing a new volume of puzzles by celebrities. The Talk of the Town writer says that he has a puzzle in the book, which, he tells us blushingly, “’they” say is one of the best. Through some literary detective work, I ID’d the writer/puzzle constructor as advisory editor Marc Connelly.******

Worst Description

A profile on Giulio Gatti-Cassaza, manager of the Metropolitan Opera, describes his nose as follows: “It is a fine, memorable feature, this Gatti- Cassaza nose. It is the sharpest, most assertive part of his wise, sensitive, melancholy face.” If this description leaves you feeling insufficiently well informed about G G-C’s nose, the profile includes two more sentences about it.

To this day, the New Yorker retains what a writer for the magazine described in 2012 as “a literary commitment to tiny details, combined with a comedic eye for social types.” Whether you think this is a good or bad thing depends on how much you want to know about people’s noses.

Best Description

A brief item in a section called “The Hour Glass” describes New York State Senate minority leader (and future New York mayor) James J. Walker thus: “His face is thin; his features sharp, and his cheeks have the perennially youngish tint of the juvenile who bounds onstage as the chief chorine shrills: ‘Oh, girls, here comes the Prince now.’” I feel like I’ve read a similar description somewhere before, but it’s more entertaining than reading about noses.

Worst Gossip

“In Our Midst” is a column of innocuous gossip that seems intended to let us know who is cool enough to be featured in the New Yorker.******* It’s all pretty boring, so I’ll arbitrarily choose this: “Jerome (‘Jerry’) D. Kern was in town one day buying some second-hand books.”

Best Gossip

Also from “In Our Midst”: “Those are pretty clever and interesting stories about married life that Mrs. Vi Shore is writing for Liberty. Yr. corres. wonders if Mr. Shore reads them.”

Hey, New Yorker, I’ve got an idea! Maybe, instead of boring gossip, you could publish interesting short stories! In the meantime, I’m going to track down Mrs. Vi Shore’s.

Worst Criticism

The Books section includes a rave review of God’s Stepchildren by Sarah G. Millin, “a powerful story, the story, simple, direct, unfailingly real and not for a sentence dull, of what comes of white-and-black mating in South Africa. It is, of course, tragic.” I have actually read this book, for my 1920s bestseller discussion group. Meanwhile, E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, which I have, more unremarkably, also read, is given this squib at the end of the section: “A foaming-up of India race hate, pictured with searching skill.”

If it were up to me, I’d highlight the book that comes out against, not for, race hate.

Best Criticism

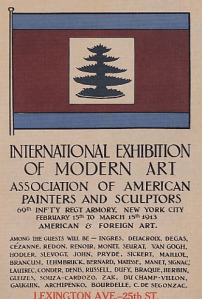

The art columnist, bylined “Froid” and actually Murdock Penderton, has this to say about an exhibition of British paintings: “If you are a person who quit trading with the corner grocer because you believed him a German spy, you will enjoy this exhibit.…A placard with sufficient fairness warns you that this exhibit is held in the interest of further cementing the bonds of the English speaking races….If you care for anything later than Ingres, stay at home and let the cement of the English speaking races crumble away.”

Worst Going On

I want to attend almost all of the goings on on “THE NEW YORKER’S conscientious calendar of events worth while.” I do not, however want to go to “Dinner to Gen. Summerall, Hotel Plaza. Tuesday, Feb. 17, given by a citizens’ committee, Gen. John F. O’Ryan, chairman.” I’m sure the Gen. is a nice guy and all, but I was a diplomat for 28 years and I never, ever want to go to another dinner with speeches.

Best Going On

“Lady, Be Good—Liberty Theatre. A nice little musical comedy, with the enviably active Astaires and the most delightful score in the city.”

Adele Astaire, Fred’s sister and dance partner, called the story line “tacky” and “weak,” but who cares? The Astaires! A Gershwin score! Sigh. I had to satisfy myself with a 1966 broadcast of Fred Astaire singing the show’s two big hits (“Fascinating Rhythm” along with the title track) and shuffling around a little.

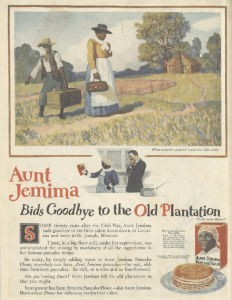

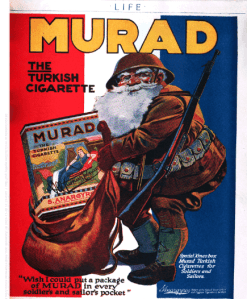

Worst Ad

“What’s wrong with this friendly welcome?” you might be asking. But there’s Sarah G. Millin again, who has written, the ad says, a “strange, great, darkly beautiful novel.” I’ll give them strange.********

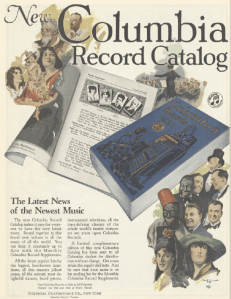

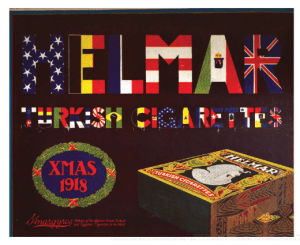

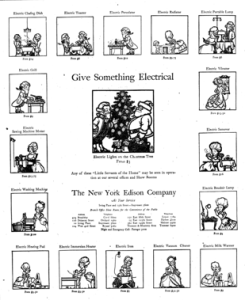

Best Ad

If the map is as stylish as this ad, I’ll pay $1.50 for it.

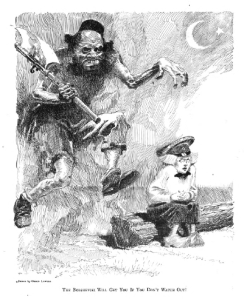

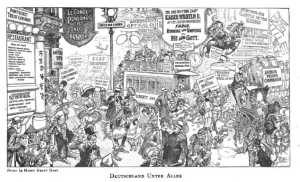

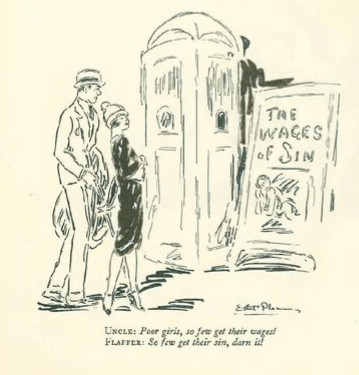

Worst Cartoon

There were only six cartoons, and they were all okay, so I’ll yield the floor to Time magazine, which complained that the magazine contained “one extremely funny original joke, tagged, unfortunately, with a poor illustration.” Given the absence of other contenders for extremely funny original joke, it has to be this one, by Ethel Plummer, who only submitted a few more cartoons to the magazine.

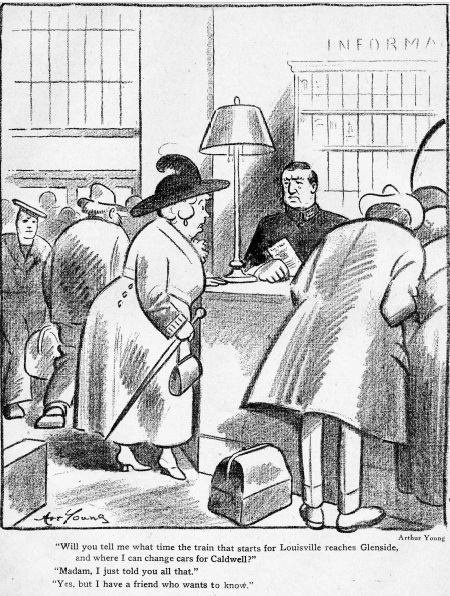

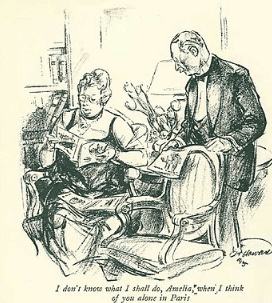

Best Cartoon

I wouldn’t say this had me in stitches, but it’s a quintessential New Yorker cartoon, the type you might expect from Helen Hokinson in the 1940s.********* Like Plummer, though, cartoonist Oscar Howard only made a few appearance in the magazine.

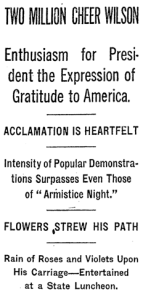

All in All…

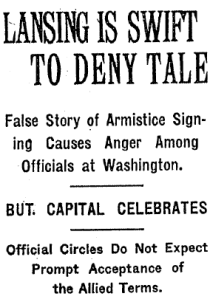

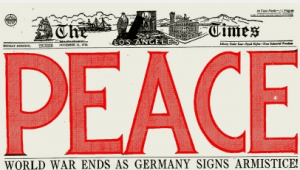

The critics were right: the magazine is sophomoric and trying too hard. It’s difficult to tell whether it’s celebrating or skewering its subjects. And it’s horribly racist. Looking at the first issue, though, you can see flashes of what’s to come. It’s there in the typeface (designed by Irvin), in the drawings, and in the sections, many of which have survived. (There’s even one of those pieces of filler with a newspaper headline and a snarky comment. Not a funny comment, but it’s a start.)

Ross was frank about the New Yorker’s flaws, writing in the first issue that the magazine “recognizes certain shortcomings and realizes that it is impossible for a magazine fully to establish its character in one number.”

It will take a while, but the bones of a great magazine are there.

*Time itself had debuted two years earlier, on March 3, 1923. I read the first issue but didn’t get around to doing a post. The highlight for me, as an amateur T.S. Eliot scholar, was an article reporting speculation that The Waste Land was a hoax.

**That is, if you think 60 is old, which I, with skin in this game, don’t.

***According to a piece on Tilley in the New Yorker’s 80th anniversary issue in 2005, his name came from a series of humorous pieces by staff writer Corey Ford during the magazine’s first year.

****Not that I’m in a position to criticize this choice of material, having written an entire blog post making fun of George Jean Nathan and H.L. Mencken’s love lives.

*****As I noted in my post on children’s books of 1924, publisher Simon & Schuster called them “cross word puzzles.” The New Yorker, in its first issue, calls them cross-word puzzles. On the other hand, they write “teen-ager” to this day, so they’re not exactly my go-to source on hyphenation.

******Connelly, like several of the magazine’s other advising editors, was a member of the Algonquin Round Table. The other advisory board members on the masthead were Ralph Barton, Rea Irvin, George S. Kaufman, Alice Duer Miller, Dorothy Parker, and Alexander Woollcott. (In 1925, “celebrity” meant someone who was notable, not hugely famous.)

******* Other people whose mundane activities the New Yorker deems worthy of mention include writer Don Marquis, Bookman editor John Farrar, humor writer Donald Ogden Stewart, actress Norma Talmadge, and bunch of people I’m not enough of a sophisticate to have heard of. To be fair, the definition of “gossip” at the time was more along the lines of “bits of news” than “delicious scandal.”

********Millin is, the ad says, the literary editor of the Cape Town Times. Except that’s not the newspaper’s name—it is, and was, the Cape Times. I realize that this is an extremely niche complaint.

*********Hokinson made her debut in the magazine’s July 4, 1925, edition.

New on Rereading Our Childhood, the podcast I cohost: