1925 is the best children’s book year ever!

Or a total washout!

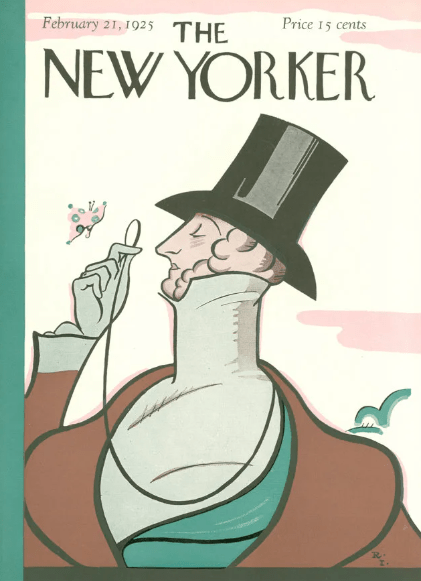

It depends on whether you believe the New York Times, whose anonymous critic tells us in its November 8 holiday children’s book roundup that “never since man began to make books, have there been so many and such beautiful books for young readers,” or The Outlook, where Edmund Pearson, writing in the November 11 issue, agrees about the abundance of beautiful books but adds, “but—and this is a perennial but—the number of juvenile books of merit is exceedingly small.”*

I had no choice, then but, to go through the books and make up my own mind, which I did with such excessive thoroughness that I’ve blasted right past Christmas. This might have stressed me out more, with seven on-time holiday children’s book roundups under my belt,** if I hadn’t heard the wise counsel, on the holiday episode of Caroline O’Donaghue’s*** podcast Sentimental Garbage, that we should stop stressing out about traditions and instead think of them as “things we like to do sometimes.” So, sometimes I like to post my children’s books holiday roundup in time for Christmas.

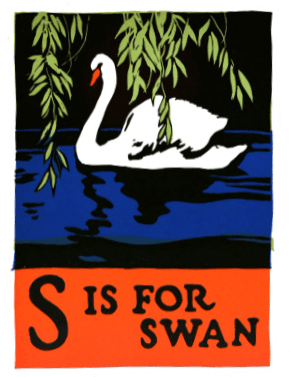

For the Youngest Readers

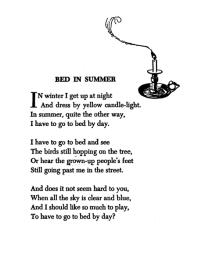

There are always a lot of reissued classics by noted illustrators, and 1925 was no exception. The year’s crop includes A Child’s Garden of Verses, Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1885 collection, with illustrations by Jessie Willcox Smith. Smith’s black-and-white illustrations aren’t particularly memorable, and some of the poems

hold up better today than others,

but Smith’s color plates do Stevenson’s poems justice.

A.A. Milne, who had a huge success with When We Were Very Young in 1924, is all over the place in 1925. A Gallery of Children is a collection of stories with illustrations by Henriette Willebeek LeMair. Pioneering children’s librarian Annie Carroll Moore**** tells us in an October roundup in The Bookman that Milne wrote the stories to go with the pictures rather than the other way around, and it shows. The pictures are indeed wonderful, but the stories are a mixed bag.

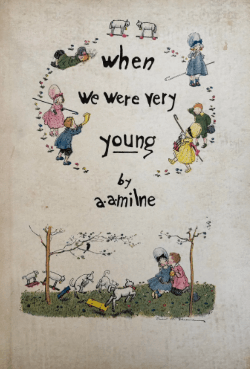

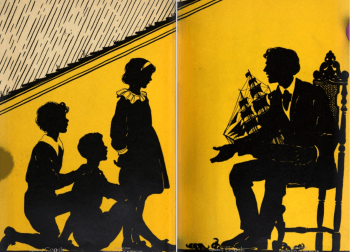

So if you’re going to go with Milne this season you might want to opt for When We Were Very Young, which is out in a new holiday edition, larger in size, and, as Marcia Dalphin is all excited to tell us in a December holiday children’s book roundup in The Bookman, with a picture of Christopher Robin as a frontispiece. I couldn’t find the original edition, so I don’t know if the frontispiece wasn’t there in that one or if Dalphin just wasn’t paying attention back in 1924. So that we can all share in the excitement, here it is.

For Middle-Grade Readers

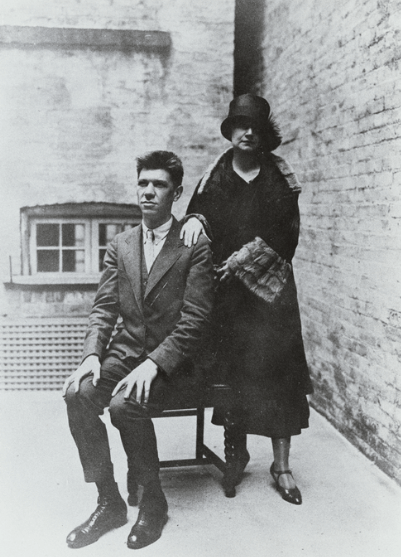

David Goes Voyaging, written by twelve-year-old David Binney Putnam, is the story of his experience as a cabin boy on the Arcturus expedition, a six-month-long journey to the Sargasso Sea and the Galapagos islands led by naturalist William Beebe. David’s age led me to suspect that he was yet another fake child author, but a look at the text convinced me that it was written by an actual twelve-year-old: “The writing took quite a long time, and I think being a naturalist would be more fun than being a writer. Anyway, my stories help me remember the fun we had on the Arcturus. I don’t see how it could have been much better.” David’s father was the promoter George Palmer Putnam, who married Amelia Earhardt in 1931, and David would go on to have a number of other adventures dreamed up by his publicity-hungry father.

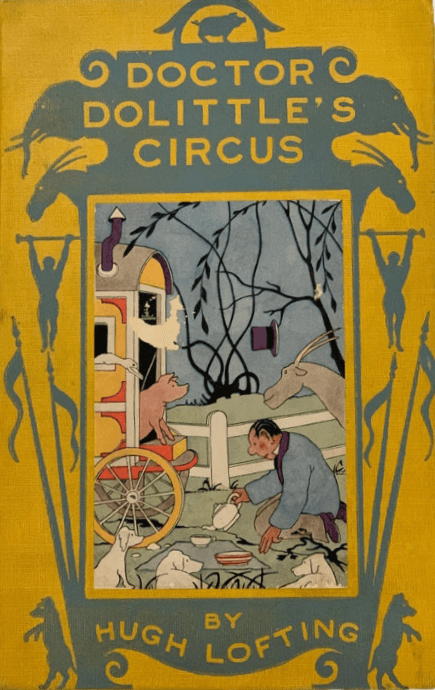

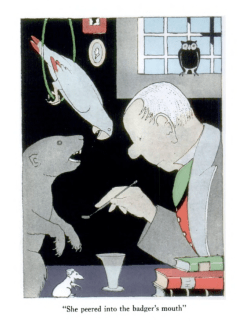

At the beginning of Dr. Dolittle’s Zoo, written and illustrated by Hugh Lofting, Dr. D’s parrot Polynesia bemoans the addition of yet another installment to the series, the fifth since the publication of Dr. Dolittle in 1920. This one, about a cageless zoo where the animals can leave whenever they want, seems to be one of the more innocuous installments in the sometimes horribly racist series.

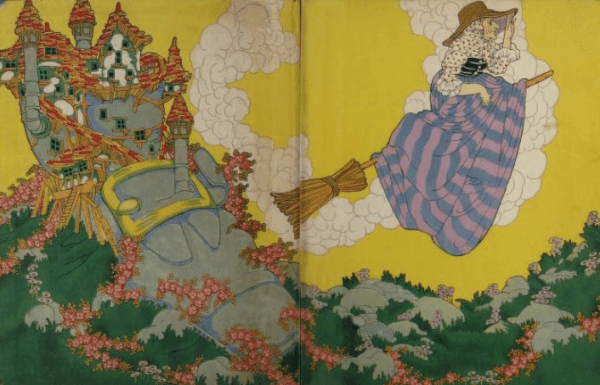

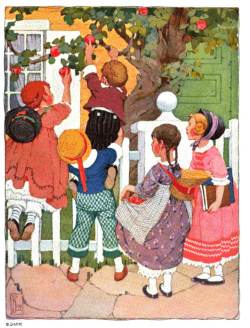

Adventures in Our Street, written and illustrated by by Gertrude A. Kay, starts promisingly with these endpapers,

but the characters are all referred to by names like Two-Braids and the Door Slammer, which I took as a bad sign at first. The book turns out to be witty, though, as well as being beautifully illustrated. I even warmed up to some of the children’s epithets, especially The-Children-Who-Broke-All-Their-Toys-on-Christmas.

In Dorothy Canfield Fisher’s Made-to-Order Stories, it’s the author’s 10-year-old son Jimmy who’s giving the orders. He draws the line at fairies “because they’re foolish,” hates things that couldn’t possibly have happened, and despises stories that try to teach you something without your knowing it. Jimmy shows up at the beginning of each story, giving instructions, and again at the end, quibbling about plot holes. Jimmy went on to be an army surgeon in World War II and, sadly, died in the Philippines in 1945.

The Joy Street anthology series is coming off a rough year: Anticipating the third volume, Annie Carroll Moore says in her Bookman roundup that Number Two was “so disappointing to children that we reluctantly withhold our recommendation until we have sampled its contents with children under ten years old.” I checked out one story in Number Three Joy Street, “The Princess Who Could Not Laugh” by, you guessed it, A.A. Milne. What finally made the princess laugh was someone slipping on a plate of butter. Not being a fan of slapstick, I’m withholding my recommendation too.

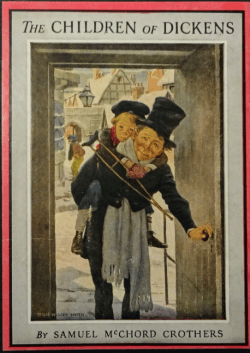

Reading The Children of Dickens by Samuel McChord Crothers is like being stuck next to someone at a dinner party who insists on recounting the plots of one Dickens novel after another. Jessie Willcox Smith contributes charming illustrations, though.

Shen of the Sea by Arthur Bowie Chrisman is the year’s Newbery Medal winner, but I had a hard time getting into it. People say “honorable” a lot. The author of a post on the book on the blog Orange Swan, who had more perseverance than I did, called both Chrisman’s stories and Else Hassleriis’s illustrations “faux Chinese” and noted that Chrisman had never visited China.

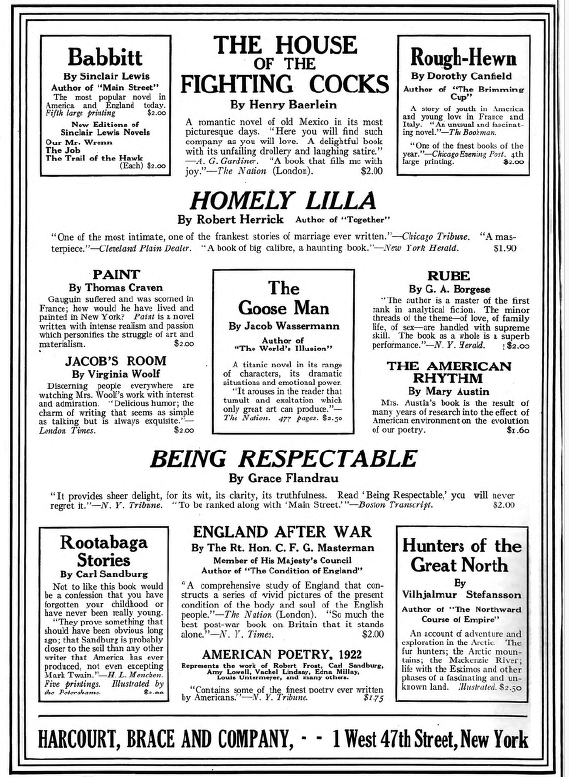

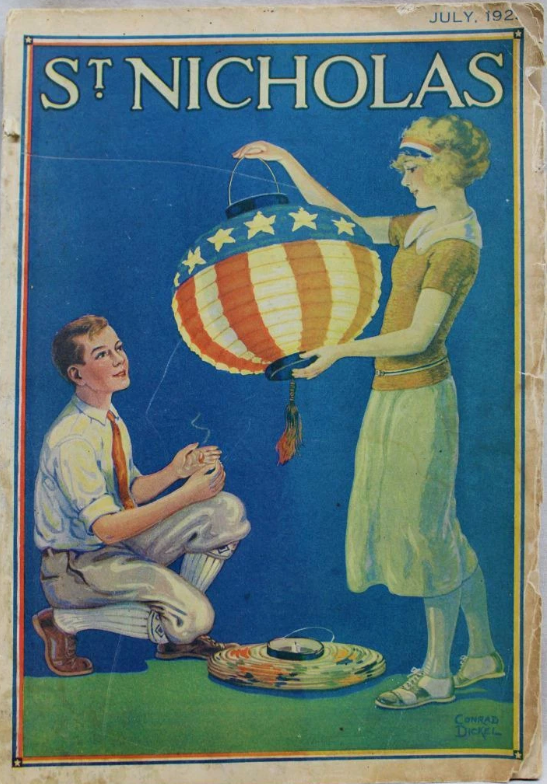

The Rabbit Lantern, a collection of stories about Chinese children, didn’t appear in any reviews, let alone win a Newbery (I spotted it in an ad alongside the roundup in The Outlook). Author Margaret Rowe and illustrator Ling Jui Tang have way better China credentials than Chrisman, though. Rowe grew up in China, the daughter of missionaries, and Ling Jui Tang, according to the ad, was Chinese. I’m not qualified to judge the tales’ authenticity, but the book’s a lot livelier than Shen of the Sea.*****

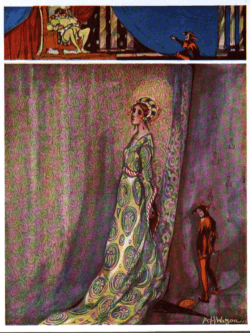

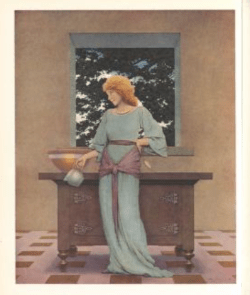

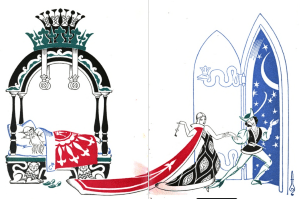

“Worth all it costs,” the Independent’s D.R. tells us of Louise Saunders’ The Knave of Hearts, with illustrations by Maxfield Parrish. Someone tore out the part of the page where the price was listed, though, so I don’t know how much that is. The illustrations by Parrish make up for the text, which is in the form of a long, tedious play.

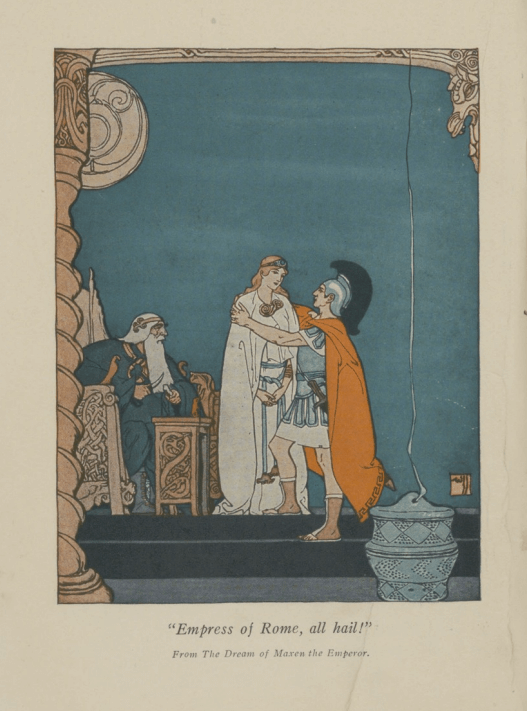

Marcia Dalphin tells us in The Bookman that The Forge in the Forest by Padraic Colum is “a book with a fine stirring atmosphere in it, and the stroke of iron and iron.” Alice M. Jordan tells us in the Independent that Boris Artzybasheff’s illustrations have “a half-barbaric quality.” My brain can’t absorb another folk tale at this point, so I’ll take their word for it.

For Older Readers

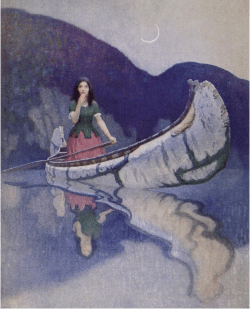

Dalphin comments that, for older children, “stories of distinction are hard to come by”—a problem I’ve observed year after year in this age group. There are a number of re-illustrated classics on offer, including James Fenimore Cooper’s The Deerslayer, with illustrations by N.C. Wyeth,

an abridged edition of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, with illustrations by Mead Schaeffer,

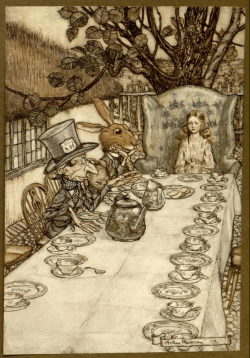

and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham.

The Flying Carpet, an anthology of poems and stories by noted writers, has been getting a lot of buzz. Contributors include Thomas Hardy, with just a short poem at the beginning, and, again, A.A. Milne, with a poem that will appear in his 1927 collection Now We Are Six.

The highlight for me, though, is a story by Peter Pan author James M. Barrie called “Neil and Tintinnabulum,” about a seven-year-old boy who’s sent off to boarding school. Barrie tells it in a meta way, saying at one point of a plot twist, “The situation is probably unparalleled in fiction.”

Every year I check out the latest Cornelia Meigs book, and every year I regret it. Rain on the Roof starts out with, yes, rain, and then the sun comes out, and then there’s a swallow, and…I’m done. The endpapers are cool, though.

Alice M. Jordan, writing in the Independent, has this generic praise for Friends and Rivals by Arthur Stanwood Pier: “A real story with real characters.” After initially thinking, “Wait, isn’t that the gay hockey show?” (no, that’s Heated Rivalry), I checked it out and found myself getting into the story, about a sickly young man with a coddling mother who goes to boarding school and presumably—I didn’t get that far—joins the football team.

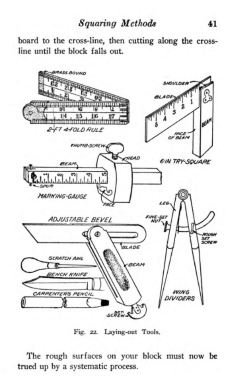

For the mechanically minded, there’s The Practical Book of Home Repairs by Chelsea Fraser, which Edmund Pearson, writing in The Outlook, calls “a severely practical volume” for boys and men. If the young person in your life is into soldering and repairing the water supply, this is just the thing.

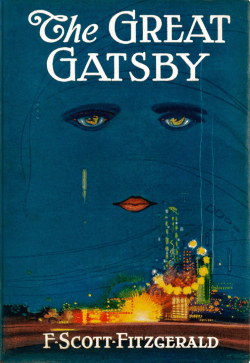

If not, how about giving your young friend a book full of love and parties and heartbreak and jazz and flowing white dresses? It got so-so reviews, but trust me on this one.

For All Ages

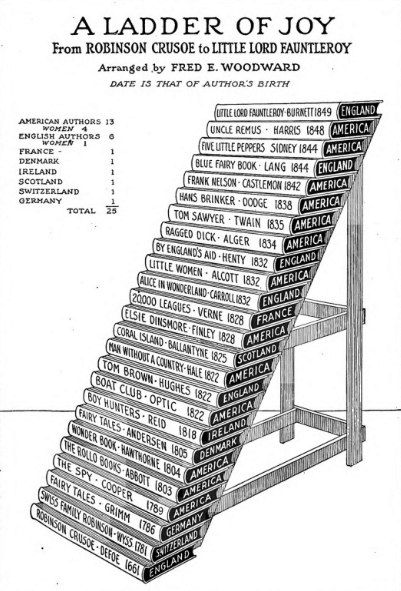

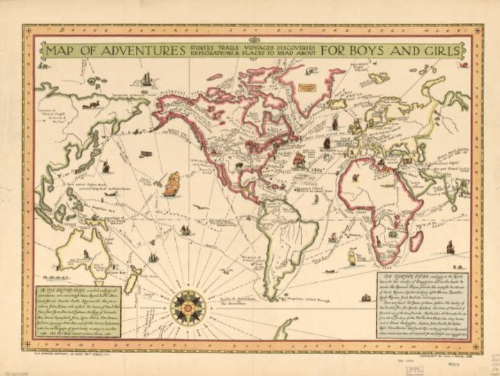

If you can’t choose just one book, this Map of Adventures for Boys and Girls features 150 fictional and real-life adventures from children’s books throughout the ages. It is, Library Journal tells us, available free of charge from the Syracuse Public Library. Many of the adventures don’t hold up to contemporary sensibilities, but as an illustrated guide to the history of children’s reading it’s a marvel.

The Verdict

I have to say that I agree with Pearson that the number of children’s books of genuine merit published in 1925 is small. It’s an era of brilliant illustrators, and of advances in printing technology that allow for numerous color pages in vivid hues. With a few exceptions, though, it’s not an age of brilliant children’s writers. There aren’t any new books on this list that children are still reading today. But that’s not unusual—most years don’t give us a children’s book that will stand the test of time.

Some years do, of course—stay tuned for 1926!

*Pearson, a librarian and true-crime writer best known for a book about the Lizzie Borden case, does not seem to have been in a particularly good mood when he wrote the Outlook column. It ends with this writeup of The Fat of the Cat, and Other Stories by Gottfried Keller, translated by Louis Untermeyer: “My informant told me that it was one of the very best books of the season. I pass this information on for those who like to read about cats. I don’t. In my opinion, there are only two good cats in literature; one of them is in ‘Huckleberry Finn’ and the other is in ‘Penrod:’ one is dead and one is down a well.”

**Granted, sometimes it was down to the wire—last year’s roundup appeared on Christmas night.

***O’Donaghue is also the author of The Rachel Incident, one of my favorites of the books I read this year—high praise since this was one of my best reading years ever.

****Annie Carroll Moore, whose first name was actually Annie, officially changed it to Anne in her fifties to avoid confusion with another woman named Annie Moore who, what are the odds, was also writing about children’s libraries. Personally, I think she should have gotten dibs on Annie, having basically invented the profession of children’s librarian. In any case, she’ll always be Annie to me.

*****Rowe later ended up in a tragic love triangle involving her husband, who was a curator of Asian art, and a visiting linguist who, according to an account of the affair in the New York Times, was beguiled by the “Orientalism” of the Marches’ Detroit home.

New on Rereading Our Childhood, the podcast I cohost: Our Favorite Picture Books